Dirty Money

The fight to control one of the biggest polluters in U.S. history, and what it means to Texas.

Read More: Back in Business?

For more than a century, the American Smelting and Refining Co. extracted heavy metals from the earth, hauled them to smelters, and refined them into the lead, zinc, and copper products that fueled industry. Under the stewardship of exceedingly rich men, the company earned enormous profits while its industrial processes poisoned poor communities in nearly two dozen states. Now, with the company’s future in doubt, the pollution may outlive the company that produced it.

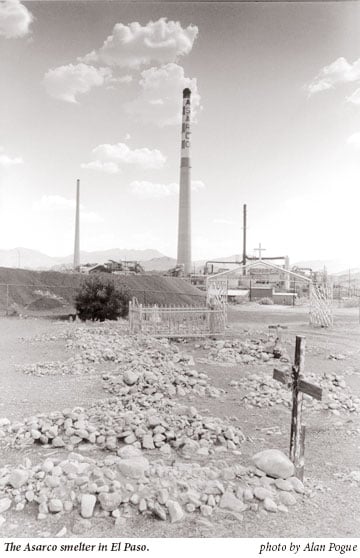

American Smelting and Refining-better known as Asarco-was formed in 1899 by a group of industrialists that included William Rockefeller. In 1901, the Guggenheim family wrested control of the company from Rockefeller and expanded it. Asarco would become the nation’s third-largest copper mining and smelting company. Asarco owns 38 facilities nationwide, including three in Texas: a metal refinery in Amarillo, a metal waste-treatment facility in Corpus Christi, and most notoriously, a smelter in El Paso that spewed lead and arsenic into surrounding neighborhoods for decades.

A century of pollution has made Asarco one of the dirtiest companies in American history. The company is responsible for 75 contaminated sites in 21 states, including 20 Superfund sites, according to federal court documents. Asarco is the subject of more than 95,000 asbestos-related personal injury claims totaling $750 million. In Texas alone, the state’s environmental commission says it will cost more than $52 million to sweep away decades of lead and arsenic contamination from Asarco’s smelting operations in El Paso. Nationwide, U.S. government officials estimate it will cost $7 billion to clean up Asarco’s pollution-one of the most expensive environmental legacies the United States has ever seen.

In 1999, Asarco was purchased by the Mexican billionaire German Larrea Mota-Velasco. Larrea is the head of a family dynasty that owns Grupo Mexico, a sprawling company that controls gold, copper, and silver mines in Latin America and that owns Mexico’s largest freight railroad. He seemed next in the line of industrialists to profit handsomely from Asarco.

Not long after Larrea bought the company, Asarco’s fortunes began to decline. Copper prices plummeted, and the company began to hemorrhage money. Its finances were in such dire shape that it couldn’t provide gasoline to its mining trucks, according to court records. The smelter in El Paso was shuttered because of depressed copper prices. Asarco’s environmental liabilities continued to mount. The company had net losses of more than $680 million between 1999 and 2002, according to court records.

In 2005, Asarco filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. The resulting bankruptcy case has been one of the most complex anyone has ever seen. After three years of legal jousting by enough lawyers to populate a small town, the bankruptcy court placed Asarco up for auction. Larrea bid to regain control of his own company. But in May, another major contender entered the bidding. Indian billionaire Anil Agarwal, a man nearly as rich as Larrea, offered to buy Asarco, putting the two in a fight for control of the company. The bankruptcy court seemed to favor Agarwal’s bid. In early October, the Indian mining magnate tried to withdraw his offer.

Neither Larrea or Agarwal-like many in the mining industry-has a stellar environmental record. And neither billionaire has committed to fully cleaning up Asarco’s widespread pollution. Environmentalists and some government regulators worry that Asarco’s bankruptcy eventually will force taxpayers to pay for the cleanup.

No one knows for sure who will own Asarco, how it will operate, or if it will even operate at all. The one certainty is that the company’s arsenic and lead contamination won’t disappear. In El Paso, heavy metals still saturate an entire neighborhood. The question hanging over Asarco’s bankruptcy is who, if anyone, will sweep away the company’s toxic legacy.

On a hot afternoon in June, the 54-year-old Larrea, one of the world’s richest men, took the witness stand at the federal courthouse in Brownsville. It was the first time many of the people inside the courtroom-including attorneys on his payroll-had ever seen the reclusive Mexican billionaire. There are few available photos of Larrea and little public information about his private life. He had fought the federal subpoena compelling him to testify for days. He had finally relented and flown into Brownsville on his private jet from Mexico City earlier that morning. Security guards had banned photographers from the front steps of the courthouse. Shortly before his testimony, Larrea was whisked into the courtroom under the escort of several armed U.S. marshals, who remained on site throughout his five hours on the stand.

Seated in the witness chair, Larrea glowered at the 30 lawyers in the courtroom-representing Asarco, and Grupo Mexico-business reporters, miners, and large, moveable bookcases of evidence that had been wheeled into the room. Larrea had come to defend himself in a lawsuit alleging that he had defrauded Asarco’s creditors.

The case in which Larrea was testifying is an outgrowth of the bankruptcy. When Asarco filed for Chapter 11, federal Judge Richard Schmidt removed Asarco from Larrea’s control. Bankruptcy experts say this was a highly unusual move. Larrea’s Grupo Mexico still technically owns the company, but no longer has any say in operations. The judge appointed a three-member independent board to oversee Asarco (the board remolded the company into an entity called Asarco LLC). The board is supposed to ensure that the company isn’t deceiving several hundred creditors with unpaid contracts and asbestos claims.

Controlled by the independent board, Asarco LLC then sued its former bosses at Grupo Mexico. The lawsuit alleges that Larrea had defrauded Asarco’s creditors by swiping Asarco’s most valuable asset-Peru’s largest copper company. The Peruvian mines’ stock was worth $8.25 billion at the time the lawsuit was filed in 2007, according to court records, though Larrea transferred the mines from Asarco to a Grupo Mexico subsidiary at a grossly undervalued price, $756 million, according to the lawsuit. The suit accuses Larrea of bilking creditors out of billions of dollars. “The plaintiff contends that the sale, therefore, was not made to improve Asarco’s financial position, but was solely a means for Grupo to ‘cherry-pick’ Asarco’s most prized asset before it was lost to creditors or by bankruptcy,” the suit alleges. Asarco LLC wants the value of the Peruvian company stocks returned to Asarco LLC creditors.

The lawsuit is a legal sideshow to the larger bankruptcy case. But the outcome of the lawsuit could have a huge impact. Some of the money at stake in the lawsuit over the Peruvian mines could help pay for cleanup of Asarco’s environmental pollution. (The U.S. government considers the Peruvian mines a crucial asset in paying to clean up Asarco’s many toxic sites.)

On this June day in Brownsville, Larrea had come to tell his side of the story. Federal Judge Andrew Hanen had to silence the courtroom before Larrea could begin his testimony. The CEO wore a conservative, well-tailored, dark blue business suit with a red tie. For such a powerful man, Larrea was surprisingly soft-spoken, answering the lawyers and judge in a hushed and barely audible, but fluent, English. Several times, the judge asked him to speak louder so that people in the back of the courtroom could hear.

Larrea repeatedly denied that his motive for purchasing Asarco was to gain control of the valuable Andean copper mines. The CEO said the decision on the mines was solely the opinion of some Asarco and Grupo Mexico officials. (U.S. marshals ensured that no journalists could get within speaking distance of the billionaire.) In a separate statement from his company, he called Asarco LLC’s lawsuit “reprehensible.”

His history with Asarco began in 1999, when Larrea took over as CEO of Grupo Mexico shortly after his father’s death. One of his first purchases was Asarco, for $2.2 billion. At the time, however, the once-powerful Asarco was hemorrhaging cash.

Initially, Larrea testified in Hanen’s courtroom, he believed the company’s growing environmental liabilities could be solved through negotiations. “In those days, we were confident we could reach an agreement with all parties on the remediations,” Larrea said. “But then the company started losing too much money on legal issues.”

By 2002, officials in the U.S. Department of Justice worried that Asarco would sell off its most valuable asset-the Peruvian mines- and would be left with nothing to pay for its numerous environmental cleanups. The department sought an injunction to stop the sale. Negotiations between the Justice Department and Grupo Mexico labored on until the end of 2002. Finally, Grupo agreed to fund a $100 million trust to help pay Asarco’s $1 billion in environmental liabilities at the time.

It was a good deal for Larrea. The Justice Department allowed Larrea to proceed with his sale of the lucrative Peruvian mines in exchange for paying one-tenth of Asarco’s environmental cleanup costs.

At the time, Charles Miller, a Justice Department spokesperson, told the Associated Press that the $100 million was the best the government could do without destroying the company. “This is maybe one-tenth of a loaf, but it’s better than no loaf at all,” Miller said. “We were trying to get whatever we could. Otherwise, this company would be gone, and we could have gotten nothing.”

With Asarco’s loss of the Peruvian mines, creditors like the city of El Paso became increasingly worried that Asarco would file for bankruptcy. Once the company filed, creditors could be left with nothing but an empty shell of debt.

The Environmental Protection Agency had been testing and cleaning up lead, arsenic, and other contaminants on residential properties in El Paso for more than six years (see “Clean Up or Cover Up?” October 8, 2004). Many homes were still waiting for a cleanup. For almost a century, the Asarco smelter near downtown El Paso belched lead, arsenic, and other contaminants over schools, businesses, and family homes. The EPA lists lead and arsenic among the most dangerous pollutants that can cause numerous human health problems. Closed in 1999 because of dwindling copper prices, the 828-foot high smokestack looms like a slumbering giant over the city. The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality estimates it will cost $52 million to demolish the smelter, remove the contaminated soil, and monitor and treat polluted groundwater surrounding the plant, according to agency records.

Two months after Larrea’s testimony, on August 30, Judge Hanen issued his ruling in the lawsuit over the Peruvian mines. In a 190-page opinion, he agreed with the plaintiffs on three of their charges. He wrote that Grupo Mexico had fraudulently transferred Asarco’s majority share in the Southern Peru Copper Corp. to another Grupo Mexico subsidiary. Hanen also ruled that the mining corporation had conspired to transfer the stock at an artificially low price that had robbed Asarco’s long line of creditors. Hanen described the transfer of the stock as designed “to leave a cash-starved Asarco with less cash.”

Houston lawyer Irv Terrell, the lead attorney for the plaintiffs, said negotiations over damages would start October 30. “I feel great about the judge’s ruling,” Terrell said. “We’ve won in three different ways. We’ve got the belt, suspenders and another pair of suspenders holding up our case.”

Terrell said that the plaintiffs would ask for $5 billion to $6 billion compensation for the Peru mines’ stock. It’s not yet clear how much of that money Larrea and Grupo Mexico will have to pay, or how much of it will go toward environmental cleanups.

Larrea and Grupo Mexico have said they will appeal the damages and possibly take their case to the U.S. Supreme Court. The company also has said it will fight to regain control of Asarco.

“We will not stop until we get back what is ours,” Jorge Lazalde, the vice president for Grupo Mexico’s Asarco Inc. told the International Herald Tribune in June. “We are going to do absolutely everything necessary.

Larrea has more motivation now to win back control of Asarco. As copper prices have risen recently, the company is turning profitable once again. Last year, the company generated $1.9 billion in revenues because of international demand for copper. But Larrea has competition.

Earlier this year, the independent board that controls Asarco LLC put the company up for bid in a private auction. Some of the world’s largest finance and mining conglomerates bid for Asarco’s assets in June. The winning bidder was billionaire Agarwal, India’s “Metal King.”

Unlike Larrea, Anil Agarwal, 54, did not inherit his wealth. He began his rise 30 years ago as a scrap metal trader in Mumbai, India, working his way up through the trade, eventually acquiring valuable copper mines in India, Zambia, and Australia. If Agarwal buys Asarco, he will own holdings on four continents. In 2008, Forbes magazine designated Agarwal as the 164th richest man in the world, up from No. 245 in 2007. (Forbes lists Larrea and his family at No. 127.)

Agarwal’s $2.6-billion offer for Asarco provides no money for environmental cleanup or asbestos claims. To placate the U.S. government, Agarwal would create a $1.5 billion environmental trust to help settle Asarco’s considerable environmental debts, which total more than $7 billion.

Larrea didn’t give up his pursuit of Asarco. In July, Grupo Mexico submitted a competing bid, this time offering $2.7 billion. Grupo’s plan would place the El Paso smelter and 31 other sites across the United States in an environmental custodial trust. The trust would be funded with an initial $10 million to clean up the contaminated sites.

Larrea’s offer has a catch. Grupo Mexico’s plan would continue to litigate environmental claims. Bankruptcy experts say this could draw out the claims process for decades. “If Grupo Mexico fights it out on all of these claims, it could take years,” says Jay Westbrook, a University of Texas law professor and expert in bankruptcy law. “And there is no guarantee that they will still have the money to pay in the future.”

While Asarco LLC and the U.S. government applauded the Agarwal bid, environmentalists aren’t yet sold on the Indian billionaire. They’re unsure he would address the contamination wrought on dozens of communities across the country.

Another thing both Larrea and Agarwal have in common, besides being on the Forbes billionaire list, is a history of allegations that their companies are responsible for environmental pollution and human rights violations.

In May, the U.S.’s largest grassroots environmental group, the Sierra Club, and several other environmental organizations sent a letter to U.S. Attorney General Michael Mukasey asking that he review the environmental record of Agarwal’s company, Vedanta. (The Justice Department must approve a deal before Vedanta could take possession of Asarco.)

In a press release, the environmental groups described Vedanta Resources as a widely recognized environmental “bad actor.” They noted that its stock had been dropped by the Norwegian government’s pension fund over concerns about environmental and human rights abuses. The groups alleged that Vedanta caused major water contamination in Zambia and India, provided subpar working conditions for its employees and falsified documents to obtain environmental clearances in an ecologically sensitive region of eastern India.

The Texas chapter of Sierra Club wants to ensure whoever buys Asarco doesn’t back out of its commitment to clean up the company’s toxic legacy. “We feel the compliance history a

d the stewardship

f Vedanta are extremely relevant,” says Oliver Bernstein, a Sierra Club spokesperson. “We don’t want to see another instance of a company using whatever the profitable pieces are of these entities and then trying to unload the environmental cleanup burden on taxpayers.”

The Indian company apparently has soured on buying Asarco. In mid-October-just before the Observer went to press-Agarwal announced that he was having second thoughts. With the global credit crunch and China’s economic engine slowing down, copper prices are once again declining. At the moment, the federal government is holding Agarwal to his promise, but he said that he will consider buying the company only at a reduced price. The parties will participate in a negotiation on October 30 in Houston to see whether a deal can be salvaged to bail Asarco out of bankruptcy.

El Paso Mayor John Cook said it would be a devastating blow for his city if Agarwal backs out. Cook said the city doesn’t favor Grupo Mexico’s plan because there is no guarantee the smelter will finally be demolished and cleaned up. “We’ll have no choice but to start negotiating long term with Grupo Mexico,” Cook said. “I’ve been working on this for the 10 years I’ve been in public office, and I’d really like to see it finally resolved.”

Investigative reporting for this article was supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Institute.