Elements of Style

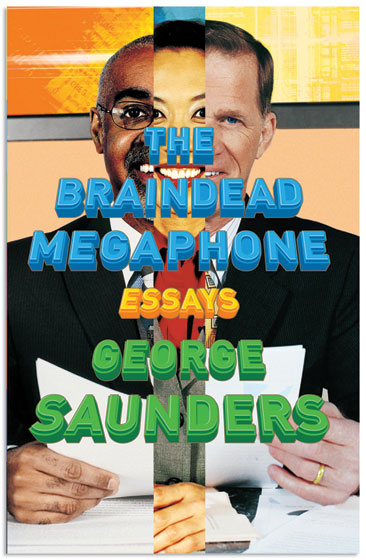

What’s striking about The Braindead Megaphone, George Saunders’ first foray into nonfiction after a decade of best-selling short-story collections and novellas, is how different in tone and intent it is from his fiction. The issues of concern are the same-consumerism, societal alienation, failures to communicate-but the approach is upside-down. His stories tend toward the cynical, even despairing, side of the human scale. The essays in The Braindead Megaphone are full of optimism and prescriptions for better living. Not self-help, but humanity-help: keys to getting on better in the world by getting on better with others. It’s as if he’s seeking to remedy the alienation and self-doubt he can’t help writing into his fiction.

The Braindead Megaphone begins with a long, eponymous essay, in which Saunders draws a metaphorical parallel between a vast, intrusive amplification system spouting uncritical nonsense, and modern American news media. News broadcasters, in their race to become ever more stimulating so as to pump up profits, have abandoned their responsibilities to the public interest, and embraced instead a “corporate model.” The result, Saunders writes, is that voices designed to inform the country have “become bottom-dwelling, shrill, incurious, ranting, and agenda-driven. It strives to antagonize us, make us feel anxious, ineffective, and alone.”

The run-up to the Iraq War in 2003 was perhaps the most glaring demonstration of how the media use rousing slogans and catchy graphics to inspire us to the least sophisticated, most antagonistic, view of the world. Saunders approaches this phenomenon with a satirical touch, which, by this point, is the only reasonable one to use. “Countdown to Slapdown in the Desert!” he imagines the megaphone spouting, as if war were a pay-per-view wrestling event. “Twilight for the Evil One: America Comes Calling!”

This is not a new argument. For years, everyone from tenured media-studies professors to Jon Stewart has criticized corporate media for condemning us to a purgatory of willful ignorance and self-imposed fear. Saunders puts a new spin on this old tale with his insistence that our travails in Iraq and our slow slide toward blind bellicosity are problems of imagination and storytelling. Leave it to a writer to reduce such a convoluted mess to something as simple as poor writing, but he has a point. “Megaphone Guy is a storyteller,” he writes, “but his stories are not so good.” Saunders argues that “the best stories proceed from a mysterious truth-seeking impulse … they are complex and baffling and ambiguous … they make us more humble, causing us to empathize with people we don’t know.” Our modern American media, on the other hand, aren’t interested in empathy or ambiguity, because empathy and ambiguity don’t sell ad space. The best way to get people to buy is to scare them into buying, and the best way to do that is to be as loud, as repetitive, and as alarming as possible, truth be damned.

“Our venture in Iraq,” Saunders continues, “was a literary failure,” and the only way to make it right is by literary means. If American politics is suffering from a paucity of imagination, then “[e]very well-thought-out rebuttal to dogma, every scrap of intelligent logic, every absurdist reduction of some bullying stance is the antidote.” In other words, books like The Braindead Megaphone are the answer.

What a brilliant conceit: The world is on the fritz; you hold in your hands the corrective. One can’t help but admire that kind of confidence.

Saunders backs up his claim with intelligence, wit, and most importantly, heart. The best writing comes in the book’s lengthy travel essays. His approach, not only to writing about places he visits but to moving around in them-how he sees them-is one of generosity that puts the lie to an American foreign policy that prides itself on ignorance, motivating the populace through anxiety and mistrust.

In Dubai, “The New Mecca,” Saunders finds, amidst the skyscrapers, theme parks, and seven-star hotels, a thousand tiny pockets of human diversity and tolerance. He talks to an Iranian cabdriver who espouses the philosophy of human sameness; he gets a lesson in the new global economy from an Indian stair-washer; he goes to Arabian Ice City, where kids play in man-made snow while their parents, dressed in traditional Arab clothing, videotape their adventure. He experiences the lives of “others” and finds them the same as the lives of those he knows back home in megaphone-land: same concerns, same loves, same fears. Watching those desert-reared kids cheerily packing their first snowballs, he thinks, “If everybody in America could see this, our foreign policy would change.”

In his other travel essays, one in Nepal, the other along the border between Mexico and the United States, Saunders notices repeatedly these “universal human laws-need, love for the beloved, fear, hunger, principle …” that transcend geography and politics. “What a powerful thing to know,” he writes, “that one’s own desires are mappable onto strangers.” True, he mocks the anti-immigrant Minutemen doing reconnaissance on a South Texas ranch, but even in them he sees a certain common human desire for a small, uncomplicated piece of the world. The Buddha boy in Nepal, who sat in a state of constant meditation for more than six months, Saunders asserts, is really no different from himself, aside from his level of discipline; the other, more cultural distinctions are mere window dressing. So he spends a freezing mountain night in the boy’s company, trying to capture at least some small sense of what his life is like: “Soon I’m making no effort to stay awake or, ha ha, meditate: just trying not to freak out, because if I freak out and flee into the Nepali darkness, it will still be freezing and I’ll still have eight hours to wait.”

No one said empathy would come easy; it’s a cold, indifferent world we live in. Best to wear something warm.

If the great crime of the “braindead megaphone” is its poor storytelling ability, then it makes sense that Saunders would find sociopolitical value in the acts of writing and reading. Witness one of his essays on the art of literature, “Thank You, Esther Forbes,” which is, on the surface, a description of Saunders’ first encounter with a great writer, but is really about the act of word choice and syntax-manipulation as means to take responsibility for your thoughts. Saunders picks apart the act of writing a sentence as a metaphor for the whole anti-megaphone approach to living: Lazy writers never bother to change the inflection of their sentences because, like lazy thinkers and passive observers, they never bother to change the inflections of their minds. “The process of improving our prose,” he writes, “disciplines the mind, hones the logic, and, most important of all, tells us what we really think.” Being told what to believe and then believing it doesn’t make us thinkers; it makes us robots or dogs. It makes us victims of the megaphone and accomplices in the kind of nefarious nonthinking that’s been defining U.S. foreign policy for the better part of a decade, if not longer.

Which is to say that Saunders is onto something, something that justifies the 250 pages of The Braindead Megaphone. God knows there are dozens of other essayists with greater command of the written word; hundreds of other sociologists with more sophisticated understandings of the ways of the world; other satirists who are more adept at popping balloons; and probably a few travel writers more able to translate the smells and sounds of distant cultures to the page. But few writers of Saunders’ stature possess his optimistic belief in the value of human understanding and generosity. As far as he’s concerned, the only answer to our current geopolitical predicament is sympathy, understanding, and an open-armed acceptance of our undeniable sameness. “I think-mumble a little prayer,” he scribbles at a water park in Dubai, “for the great homogenizing effect of pop culture: same us out! … Let us, brothers and sisters, leave the intolerant, the ideologues, the religious Islamic-Bolsheviks, our own solvers-of-problems-with-troops behind …” and find solace in our own powerless commonality.

Josh Rosenblatt is an Austin writer.