Fear and Doping in Iraq

In April 1775, villagers in Lexington, Massachusetts, watched from the road as British soldiers fired on Captain John Parker’s militiamen. Eighty-six years later, crowds of spectators in Charleston, South Carolina, observed from Battery Park as Confederate cannon fire rained down upon the Union-held Fort Sumter. In 1911, Americans in El Paso perched atop roofs and railroad boxcars to peer across the Rio Grande, where Pancho Villa was fighting the first battle of Ciudad Juárez.

War has a long history as spectator sport, and often the onlookers have no idea whether they’re watching a brief skirmish or the outbreak of full-blown conflagration.

The evening news and 24-hour cable channels have made war-watching less direct, but some still want the genuine article. Numbed by TV visions and wanting to experience something real, two young entrepreneurs decided to travel to Iraq in the wake of Saddam’s toppling, hoping to gain an understanding of the nation-building process. Ray LeMoine and Jeff Neumann were about to witness the outbreak of a fallen country’s civil war.

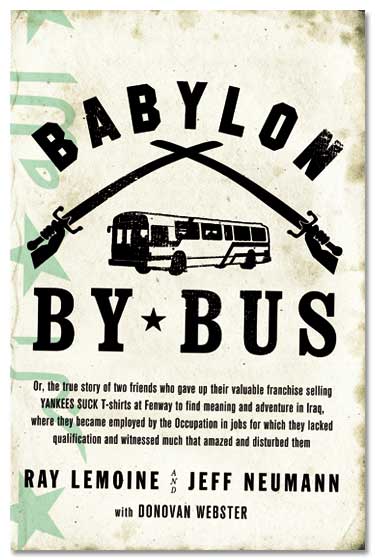

In their mid-20s, LeMoine and Neumann had established comfortable livelihoods selling “Yankees Suck” T-shirts to Boston Red Sox fans after games outside Fenway Park. Though they were essentially selling contraband without a license, business thrived, supporting the two well enough to keep them traveling between baseball seasons. “We’d been to some 60-odd countries each,” LeMoine writes in Babylon by Bus. (The book is written in LeMoine’s voice.) “We’d grown tired of the Lonely Planet scene though…. We wanted to go somewhere that mattered, someplace where we could see firsthand that concept called the Global War on Terror.”

LeMoine and Neumann figured they could put their grassroots business experience to use while getting front seats to the action. “The T-shirt thing showed us that anything is possible, and we figured: Why not try and work in humanitarian aid?” LeMoine writes. “We’d been looking for these jobs in the hottest of spots: Gaza, Baghdad, Kandahar, Peshawar … any place that would have us. We combed humanitarian and nongovernmental organization (NGO) Web sites, searching for jobs, but they only wanted Ph.D.s. Instead of applying online for a job half a world away, we decided to apply in person.”

Lest the reader begin to think their intentions too altruistic, LeMoine and Neumann readily admit to other reasons for traveling in war-torn lands. “It’s not accurate to pretend Jeff and I were simply two do-gooders trying to help babies in the Third World,” LeMoine confesses. “We also enjoyed the world’s sleazy side. … Stupid, I know. When I say we were stupid, I don’t mean that we didn’t know anything. With all our free time, we had the chance to read and read and read. Our stupidity lay not in a lack of knowledge, but rather in our application of that knowledge to dumb ideas, like buying stolen sports cars in Iraq to transport rugs, or selling offensive T-shirts on the sidewalk, or going to Gaza to get a job.”

Able to afford the ultimate reality experience with coffers stuffed from their lucrative, bootleg T-shirt business, LeMoine and Neumann set their sights on Baghdad. “Real, lethal, and constant, Baghdad was our escape from the escapism we’d been living during our T-shirt baron years on the Backpacker Trash circuit,” LeMoine writes. “Its urgency and relevancy were intoxicating.”

Aside from the war’s intoxication, LeMoine and Neumann are constantly high throughout their Baghdad memoir on a hazy stream of muscle relaxers, pot, and alcohol. “Within days, my signature cocktail became a shot of arrack and a shot of Valium with a dab of water,” LeMoine recalls (Valium is a nonprescription drug in Iraq). “Jeff called it an Arab Tom Collins.”

Although lacking the addled eloquence of Hunter S. Thompson’s overindulgent political chronicles, LeMoine’s and Neumann’s taste for the underbellies of society proves a boon for the reader, giving insight into circles of Baghdad not previously covered in the media.

Describing a sleazy watering hole in the Red Zone named the Fanar Bar, the authors draw a wonderfully vivid sketch. “British mercenaries sat with Washington lawyers from firms like Patton Boggs, while a senator from Romania ate shish kebabs with Lebanese profiteers and German reporters,” LeMoine writes. “John F. Burns of The New York Times would be at a table with Jon Lee Anderson from The New Yorker, two great war correspondents, far from home, enjoying a drink while swapping sources and info in a seedy bar. Serbian mercenaries would be talking Vlade Divac and Slobo’s trial at The Hague with State Department contractors. The same Serbians had been killing so many Muslims a decade ago that NATO bombed their country. Now, they were getting paid by NATO countries to manage Muslims. It’s funny how things worked out.”

Arriving in Baghdad by bus from Jordan in January 2004, LeMoine and Neumann were able to witness a delicate period in Iraq’s reconstruction, when success seemed possible and civil war was a muted cry. “The insurgency was still a toddler,” LeMoine writes. “In Iraq’s teahouses, restaurants, and bars-both inside and outside the Green Zone-many journalists, contractors, profiteers, and Iraqis thought the CPA [the now-defunct Coalition Provisional Authority] had a shot at avoiding a long-term guerrilla war and establishing democracy.”

Quickly landing work from the CPA, LeMoine and Neumann established an NGO called the Humanitarian Aid Network of Distribution. They traveled throughout Baghdad and Sadr City with locals distributing used clothing sent by U.S. citizens. Being an NGO, they were able to achieve tangible results on a small scale without bureaucratic impediments. Traveling in unarmored vehicles with no military escorts, LeMoine and Neumann distributed aid from mosque to mosque, observing Iraqi life up close and gaining an understanding of the culture.

Traveling unencumbered between the Green Zone, where the CPA had set up camp within Saddam’s old palace, and the Red Zone, essentially the rest of Baghdad, LeMoine and Neumann observed the vacuum world most U.S. government workers lived in. “What made it funnier was that no one in Baghdad other than the Americans called Iraq the Red Zone, and Americans spoke the word with fear, as if to enter it was to risk being set upon by the locals and eaten over a bed of shredded lettuce, like so much kebab. Of course, most Iraqis thought the same thing about people in the Green Zone.”

Describing a typical mosque scene upon their arrival, LeMoine writes, “A bullhorn sounded; a voice boomed. I popped three 10-milligram Valiums and washed them down with U.S. Army-supplied water. … About then I remembered I was a hungover Jew who was now on drugs at a mosque in a place where the only law was Islam. … The boxes were ripped open. A line formed. A Drew Bledsoe New England Patriots jersey was handed to a boy. Then a pair of shoes to a little girl, a pair of tiny jeans to another, and so on. … The crowd grew excited; borderline pandemonium broke out.”

Making contacts with sheikhs for aid distribution through an Iraqi their age named Hayder, LeMoine and Neumann watched as the younger generation sought to gain hold of their country. “The sudden fall of Saddam had created a vacuum that infected the younger majority of Sadr City with a newfound feeling of relevance and vibrancy,” LeMoine writes. “According to Hayder, it had awakened a religious nationalism in Iraq’s youth. ‘They really love Iraq, almost as much as they do the mosque. Sadr City’s future belongs to the mosque. Al-Hawza [a pro-Sadr newspaper] and Muqtada al-Sadr want to solve the problems Saddam and the Americans couldn’t.'”

With al-Sadr’s voice gaining political strength, more and more young Iraqis began calling for American withdrawal. Iraqis he met felt the coalition’s “is like living with your parents, except you don’t know them, they don’t like you, they speak a different language than you do, and they enforce their ‘belief systems’ with big guns. It’s humiliating,” LeMoine writes.

The most glaring fault in Babylon by Bus is also its greatest asset-the immaturity of its authors. At times, reading the book is like watching Werner Herzog’s documentary Grizzly Man, whose doomed protagonist is eaten after getting close to one bear too many. LeMoine and Neumann are so brazenly reckless traveling Baghdad backstreets at night that the thrill of imminent danger translates to the reader.

While they use the constant anxieties of living in Baghdad as an excuse for their drug consumption, these guys would probably be piled up stateside as well. Insights into governmental policies are often followed incongruently by dorky stoner talk, reducing the authors’ credibility. Upon entering the CPA headquarters, LeMoine observes, “To create democracy in Iraq, the Bush administration had chosen to use the one American societal tool that wasn’t democratic: the military and its chain of command.” Following this thought, LeMoine turns to Neumann and states, “‘Man, I wish we had some weed. … What a perfect spot to smoke a victory blunt.'” Victory blunt? At times, the Bill and Ted dudeness is a jarring roadblock in the narrative.

Yet LeMoine and Neumann aren’t war journalists or full-time professional aid workers, nor are they pretending to be. Essentially, they are two backpackers who manage to gain a front seat to Baghdad’s action while happening to help some needy Iraqis out. Contradictory, honest, and compelling, Babylon by Bus offers a decidedly new vantage point on the war in Iraq. Unlike the tidy, black-and-white scenarios portrayed in the mass media of early 2004, LeMoine and Neumann embody the honest messiness of the Iraqi rebuilding effort and what it means to be human.

Stayton Bonner is a writer in Austin.