Smoking for Jesus

Exiled by hurricanes, a black congregation from New Orleans takes root in the Texas Hill Country

And the flood was forty days upon the earth; and the waters increased, and bare up the ark, and it was lift up above the earth. -Genesis 7:17

They came in their Sunday best, men in matching bright purple blazers, women in dresses. The small, rural church on a lonely ridge near Marble Falls quickly filled. Once inside, they offered joyous thanks for their deliverance-from the streets of New Orleans and, two years ago to the day, from two terrible storms. In the parking lot, a few cars still bore Louisiana license plates. Christian hymns seeped from the walls of the A-frame with its tiny spire, and echoed across the quiet countryside, as if sung by the trees themselves.

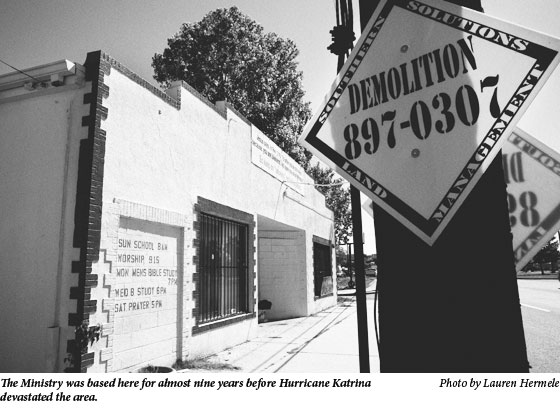

In this serene patch of Texas Hill Country, more than 200 African-American émigrés from New Orleans have found a new home. They call themselves the Smoking for Jesus Ministry. Back in Louisiana, their church was a sanctuary from the violence and poverty of New Orleans’ Ninth Ward. Many joined to escape the perils of drugs, gangs, and alcohol. Without the ministry, some would likely be in prison or an early grave.

As Hurricane Katrina bore down on the Gulf Coast, the church picked up en masse and fled. They ended up in overwhelmingly white Burnet County, where they immediately increased the black population by a third. In spite of the dramatic change, they have flourished. They did it all by clinging fiercely to their faith.

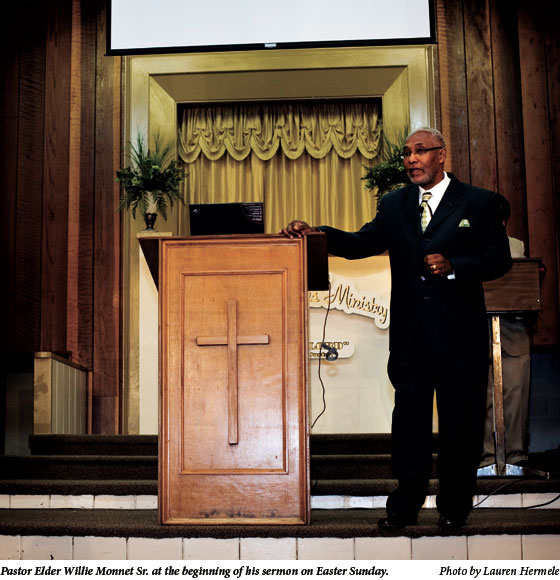

Despite the name, there is nothing whimsical or alternative about Smoking for Jesus. It’s old-school fundamentalism, a ministry based around the reformative power of the born-again experience. The pastor, a 55-year old former New Orleans cab driver named Willie Monnet, founded the church 11 years ago. He took the unusual name from Revelation 3:16: “So then because thou art lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I will spue thee out of my mouth.” The verse, Monnet explains, equates your temperature with the ferocity of your belief. “People that go to church but don’t change, they’re lukewarm,” he says. “When you’re cold, you don’t go to church, you cuss, you steal from your momma, you do all that. So don’t call on no Lord, ’cause you cold, you a sinner. Red hot means you go to church and you live right at the same time.”

In Smoking for Jesus, worship dominates all aspects of life-all day, every day. There is no drinking or smoking, and much of pop culture is considered taboo. There is only the Word. Followers describe themselves as so devout that they’re “on fire for the Lord,” and thus smoking for Jesus. There is also an implied wordplay, however, since some in the ministry are recovering addicts.

On the anniversary of the evacuation, there was much to celebrate inside their new sanctuary, with its vaulted ceiling and wood-paneled, ski-lodge decor. They sang and danced and shouted and swayed as if the church itself were on springs. A woman, consumed by the spirit, collapsed in a fit of convulsions and spoke in tongues.

After opening with songs and prayers, Claudette Monnet, the pastor’s wife, took the microphone. “[God] counseled us to be ready on that Sunday morning. He led us through all those places. … People came to see us like we were some kind of exhibit, to see how broke down we were. God wouldn’t let us be broke down!” The entire congregation stood and cheered.

Pastor Monnet then rose to speak. “This would be the Sunday we dressed in our shorts and T-shirts and came to service and packed up … I inherited about 200 children that day,” he said. “It took us 40 days to get to Marble Falls. The first three weeks were some of the hardest times. Look what He’s done-kept us together, gave us another church. And it ain’t over yet.”

Monnet explained the lesson of Katrina. You may never know where or why or how God might lead you, but you must trust in Him. Only by letting go of your free will can you truly walk with the Lord. “Worship is a sacrifice,” Monnet preached. “To do God’s will is going to cost you sacrifices of your dreams and your wants. Sacrifice it on the altar. … That’s worship. You’re going to put your life on the altar. He’s already set aside a purpose for your life. … It don’t matter what you want to do. It’s not your life.”

The ministry is an absolute hierarchy-based not only around the pastor’s warmth and charisma, but also around his interpretation of God’s will. (Many Smoking for Jesus members wouldn’t consent to an interview for this story without asking the pastor’s permission.) The willingness of church members to subjugate themselves to the pastor’s version of the Lord’s desire imbues Monnet with enormous power-some might say dangerous power. In fact, the relatives of church members who stayed in New Orleans have complained that the ministry is actually a cult.

Monnet finds the cult references amusing. Anyone can leave the ministry whenever they want, he says, but most choose to stay because the church is their family. Without the power of the Lord, he said, few Smoking for Jesus members would be saved. “You can’t do this on your own strength, your own abilities,” he told the congregation from the pulpit. “Some people think they can just work through this themselves. You can’t do it.”

The average life expectancy for a black male in New Orleans is 20. Or so Semien Williams had been told growing up. “I was like, ‘if I’m going to die when I’m 20, I’m going to live it up now.'” Dapper-dressed and devout, Williams speaks in the pillowlike tones of a talk-radio therapist. He indulged in alcohol and drugs, and though he says he never joined a gang, he hung around those in the Ninth Ward who did. Williams assumed his death would come from “being at the wrong place at the wrong time with the wrong people.” Hit with a stray bullet, probably. He fantasized about what he would do on his 21st birthday if he lived that long: “I had a plan to get drunk … and run down Canal Street butt naked.” That was before he knew the Lord.

A few months after he turned 18, Williams encountered a beautiful woman whom he had met briefly. He wanted her, and so when she parried his advances with an invitation to church, he found himself at his first Smoking for Jesus service. Williams never had much love of religion; he’d gone to church on Sundays as a youth more out of obligation than belief. Many folks in his neighborhood went to church on Sundays, but it rarely altered their behavior, he says; during the week, they sinned all the time. Monnet’s message of redemption and strength through faith struck Williams. “It was like he hit me in my face,” Williams said. “I knew he was preaching to me and my situation.” The next week, Williams returned for another service, this time alone. At the end of the service, he rose from his chair, walked to the altar, knelt and, as he says, gave his life to the Lord.

Williams’ story is a common one. At 27, he has been with Smoking for Jesus for nine years. It’s his family now.

“A lot of them have their fathers gone,” Pastor Monnet said. “So they look to me as being a father. They just wanted somebody to be concerned about them, to help them. Our purpose is to make responsible men and responsible women. So they hold jobs, raise a family, come to church, and [are] not in prison and acting crazy.”

So when Katrina was bearing down on New Orleans in late August 2005, Williams didn’t hesitate to leave his biological family. With his younger brother and sister, he joined the ministry’s caravan of more than 40 cars that left the city the Sunday before the storm hit. Monnet stayed at the ministry’s old, one-story church in New Orleans until the last car had left.

What followed was an odyssey of biblical proportions. They drove 12 hours to a Christian retreat in Lumberton, Texas, outside of Beaumont. After three weeks there, the ministry was forced to flee again, this time from Hurricane Rita. They embarked on a 19-hour haul to Longview. Later they moved on to Dallas, and then Austin, all in the span of a few weeks, never missing a service.

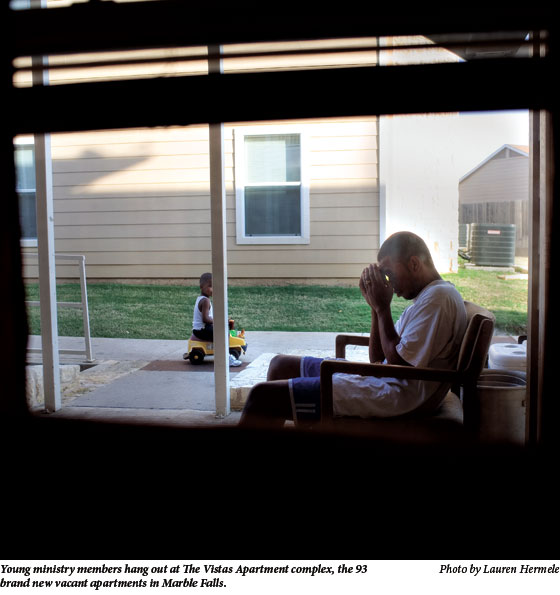

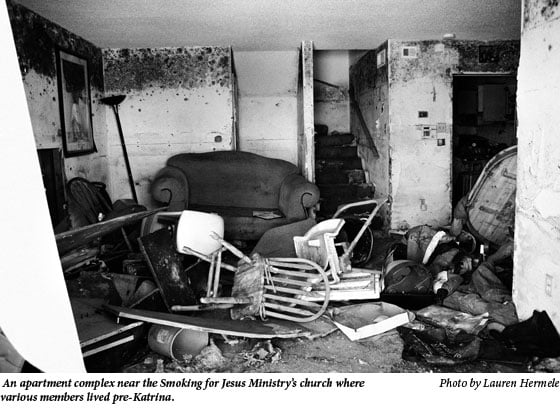

When Monnet saw firsthand the devastation in the city and the extensive damage the storm had inflicted on the ministry’s church and other properties-it owned a beauty salon, car wash, and the In the Hands of the Master Lawn Care Service, among other businesses-he knew there could be no return. After five weeks of wandering, Monnet and his wife, Claudette, heard of an apartment complex in Marble Falls that had more than 90 units available-enough room for nearly the entire ministry. The Federal Emergency Management Agency would pay their initial rents, and so Smoking for Jesus settled in the Texas Hill Country.

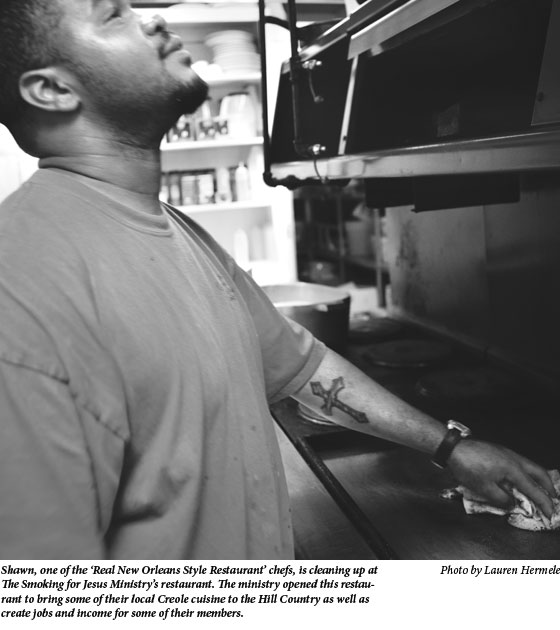

In the spring of 2006, Monnet saw an advertisement for church property for sale in the area. The ministry scooped up the building and the surrounding 56 acres. Most members have found jobs, though not all in their vocation. They give 10 percent of their incomes to the ministry from which the church derives most of its money. Some work for the church, either at the New Orleans-style restaurant they opened or in a variety of ministry programs such as bible studies and Sunday school. Occasionally Monnet returns to New Orleans with a group of men to continue the slow work of rebuilding the church’s forlorn properties, which Monnet plans to eventually sell or rent out.

The small, white Texas town has warmly welcomed the flock from New Orleans, church members say. Their white neighbors in the Vistas apartment complex offered nothing but compliments. Faith may be the bind. Marble Falls is a deeply religious place: Churches of all manner dot the roads and streets around town. At least three white families have joined Smoking for Jesus since it landed in Marble Falls, and the church members-ever welcoming with smiles and handshakes at services-hope to attract more. “This is open to everyone,” Monnet said.

Many in the ministry seem unfazed by their sudden move to a rural county-population 42,000 in 2005, according to U.S. Census estimates-that’s 81 percent white. Asked about the adjustment, they mentioned mainly mundane differences: The pace is slower, the area is quieter, more stars dot the night sky, deer can be a hazard on the roads at night. A few said they sometimes missed New Orleans and their biological families, but quickly added they have no desire to return. Only a handful of the more than 200 transplants have left the church.

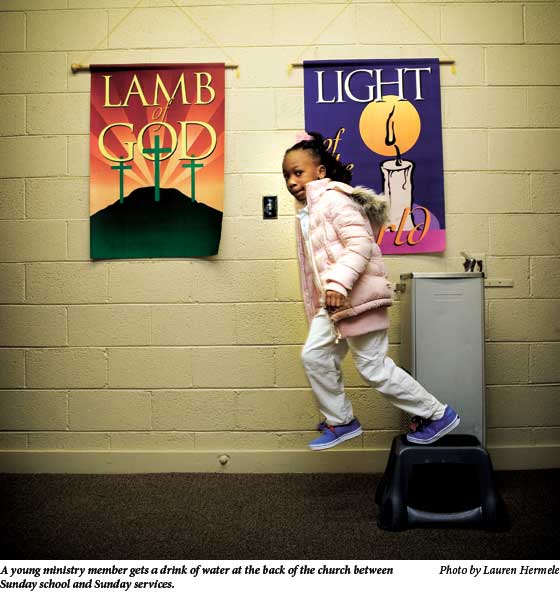

Their harmony may come from the constant embrace of the ministry’s many arms. Some members attend services several times a week, work for the ministry, live around other members. They have regrown in Texas the community they had in New Orleans.

“It’s a full package,” Monnet said. “It’s for the soul, body, and spirit. Not just on Sunday. That attracted and caused 200-plus people to stay together through the storm, and here we are.”

Monnet plans to build a compoundlike community on the 56 acres surrounding the church that will satiate nearly every need in members’ lives. They will use roughly 20 acres for the church and the ministry’s administrative offices. On 36 acres, the ministry will build houses for as many people as possible. There will be a day care center, which combined with the church’s recently opened home school, will allow the church to educate children of all ages as it sees fit.

Until recently, their children had attended public school in Marble Falls. But they began the home school so “we could teach them the principles of the word,” as Claudette Monnet put it.

The planned compound will certainly offer convenience. “You step out your front door and go to church,” said 42-year-old Sharon Summerall, who’s been in the ministry seven years. But it will also isolate parishioners on the secluded property 15 miles outside Marble Falls.

Pastor Monnet is clear about his goal: to pass what he sees as a needed sense of faith and responsibility to another generation. “If I don’t get to them, when we die, there won’t be no church,” he said.

Some ministry members’ families back in New Orleans are none too pleased. “Our family thinks [it’s] a cult and pastor is going to lead them to drink poison like Jim Jones or something,” said Jacqueline Richard, whose son, Sean, and his wife have been with the ministry for three years. Though she lives in Louisiana, she plans to move to Marble Falls soon and join the ministry. She said their family-Catholic for generations-simply doesn’t understand that “pastor is preaching the truth” straight out of the Bible, free of distortion and interpretation.

Sitting across the room in their Marble Falls apartment, Sean said, “It’s really a blessing to be here. New Orleans was real bad. There were random killings, a lot of burglaries. Out here it’s different. God pulled us out of there.” He looks at his infant son perched on his lap. “It’s a real blessing to be here.”