Teen Clockmaker Arrested in One of Texas’ Most Punitive School Districts

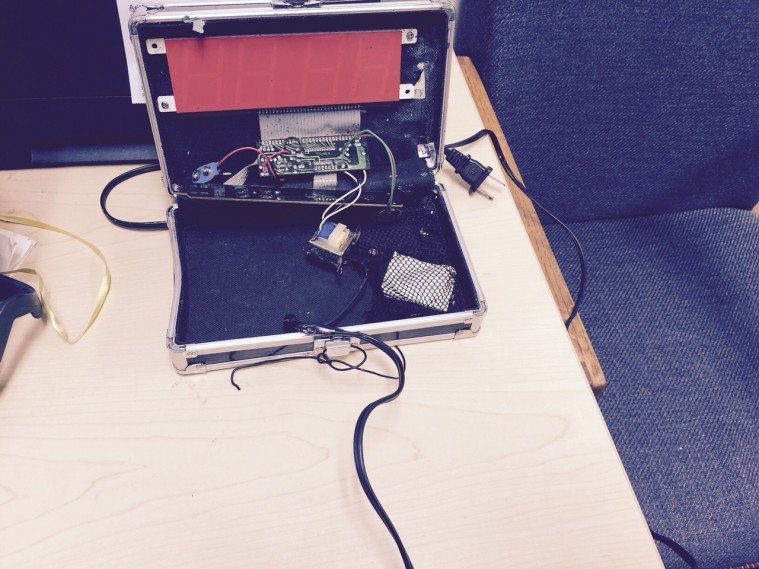

Above: Science enthusiast Ahmed Mohamed, 14, hoped to impress his teacher with his homemade clock but instead was arrested on accusations that he'd intended to build a bomb.

When we talk about how schools and police conspire to criminalize children, we have a wealth of extreme examples we can point to. There’s Noe Nino de Rivera, who spent 52 days in a coma after being tased by a school police officer at a Bastrop high school in 2013. There’s Josh Welch, a Maryland boy whose arrest after brandishing a gun-shaped Pop Tart in school prompted a bill in the Texas Legislature guaranteeing a student’s right to a small toy gun or “partially consumed pastry.” (That bill never got a hearing.) There’s Kiera Wilmot, the black Florida teen who was charged with a felony after her science experiment exploded.

And now we have Ahmed Mohamed, the 14-year-old Irving student arrested at school on Monday for carrying around a homemade clock in a briefcase. His case has struck a national nerve because the details are so ludicrous. Mohamed has said he brought the homemade clock to school to impress his engineering teacher, only to wind up handcuffed, booked and questioned by police for, they said, staging a bomb hoax.

School officials have insisted there’s another side to the story, that there was something cagey in Mohamed’s description of the “clock,” and Irving police have hinted that the boy was not entirely game while he was interrogated alone. But the story so far reflects extremely poor judgment on the school’s part. Large digital-readout clocks like the one Mohamed built, complete with your choice of red or green wires to cut, rarely come attached to actual bombs.

Mohamed’s case is also a powerful signifier of two larger stories playing out today in Irving and its schools: the cost of fear-mongering in a town where a white minority is still clinging to power, and the persistent habit public schools — particularly Irving ISD — have of turning kids into criminals.

The first of these is the ungraceful way in which the Dallas suburb has worn its sweeping demographic change. In 2009, former Observer editor Dave Mann wrote about the all-white leadership in a city where the population was half Hispanic. Then-councilman Tom Spink had recently ousted the only council member with Latino roots, running on an anti-immigration campaign and fretting that Irving had become a “sanctuary city.” As of 2013, according to U.S. Census estimates, the city’s population is 40 percent Hispanic, 31 percent Anglo, 14 percent Asian American and 12 percent African American. One-third of the city’s residents were born outside the United States. Today, its city council consists of eight men, seven of them white and one of them black, and Mayor Beth Van Duyne, who is also white.

Earlier this year, Van Duyne endorsed an effort at the state Capitol to ban Shariah law, and vowed to “fight with every fiber of my being against” an Islamic Tribunal in neighboring Dallas. WorldNetDaily reported that Van Duyne’s council hearings attracted a “room full of mostly angry Muslims,” and Van Duyne has since been welcomed aboard the North Texas tea party speaking circuit.

In a Facebook post she has since edited, Van Duyne says she does not “fault the school or the police. … We have all seen terrible and violent acts committed in schools, the workplace, and in public venues. Perhaps some of those could have been prevented and lives could have been spared if people were more vigilant.”

After Twitter boos, @IrvingMayor alters statement supporting cops on @IStandWithAhmed. "Violent acts" > "very upset" pic.twitter.com/TyHopbbvCv

— Avi Selk (@aviselk) September 16, 2015

School officials deny racial profiling — they’ve said any other student would be just as likely to have their science project confiscated, get arrested and then suspended three days — but there’s plenty of reason for the Muslim community, in Irving in particular, to be skeptical. Ahmed’s father, Mohamed Elhassan Mohamed, told the Dallas Morning News there’s no doubt in his mind: “Because his name is Mohamed and because of September 11, I think my son got mistreated.”

Now Mohamed is the toast of Twitter. He’s got Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and President Barack Obama beating down his door, inviting him to drop by the White House with his “cool clock.” A Daily Beast writer declared today that “Ahmed Mohamed Is the Muslim Hero America’s Been Waiting For.” Most importantly, Irving police have closed the criminal case against him.

For most of the students arrested in Irving ISD, that isn’t quite how it goes. Most students arrested or suspended in Irving ISD didn’t get there for building an engineering project. And most don’t get re-tweeted 11,000 times when they mention they’re meeting with a lawyer. There are many more whose cases never warrant much attention. Based on measures of school discipline, Irving ISD is one of Texas’ most punitive districts.

Going to meet my lawyer. pic.twitter.com/YCxOOeOz3Z

— Ahmed Mohamed (@IStandWithAhmed) September 16, 2015

Irving ISD, the state’s 27th largest out of more than 1,000 school districts, expelled more students than all but five districts in the 2013-14 school year, according to state data. Only four districts expelled more students to the juvenile justice system that year, and Irving ISD sent more students to disciplinary alternative classrooms than all but a dozen districts.

Like the rest of Texas schools, Irving ISD disciplined black students — which the Texas Education Agency (TEA) classifies as “African American” — at disproportionate rates. According to the TEA, African American students account for 13 percent of Irving students, but one quarter of all out-of-school suspensions. Mohamed is of Sudanese descent.

In big-picture conversations about policy, Texas lawmakers know this is a problem. Two years ago, the Legislature stripped school police officers of the ability to issue tickets for minor offenses like disruptive behavior. This year lawmakers decriminalized truancy. More and more schools are embracing restorative justice to break the cycle of punishment that has driven so many students out of school and into the criminal justice system for life.

Mohamed told the Morning News that his arrest “made [him] feel like [he] wasn’t human” and “made [him] feel like a criminal.”

That right there is the school-to-prison pipeline at work. A child learns in school that he’s a criminal, and he remembers that lesson for the rest of his life. When Mohamed returns to class with the teachers who made a judgment call and had him arrested — though he’s said he may transfer to another high school — he’ll know he’s got people across the world telling him he’s no criminal, pulling for him to succeed. The next student arrested at school isn’t likely to find that kind of support.

“We live in an age where you can’t take things like that to school,” Irving Police Chief Larry Boyd told the press conference on Wednesday morning about Mohamed’s case. But Irving students also happen to live in a school district where the penalty for “things like that” tends to be especially high.

Correction: The Irving police chief’s first name is Larry, not Robert, as the Observer originally reported. This story has been updated to correct the error.