The War at School

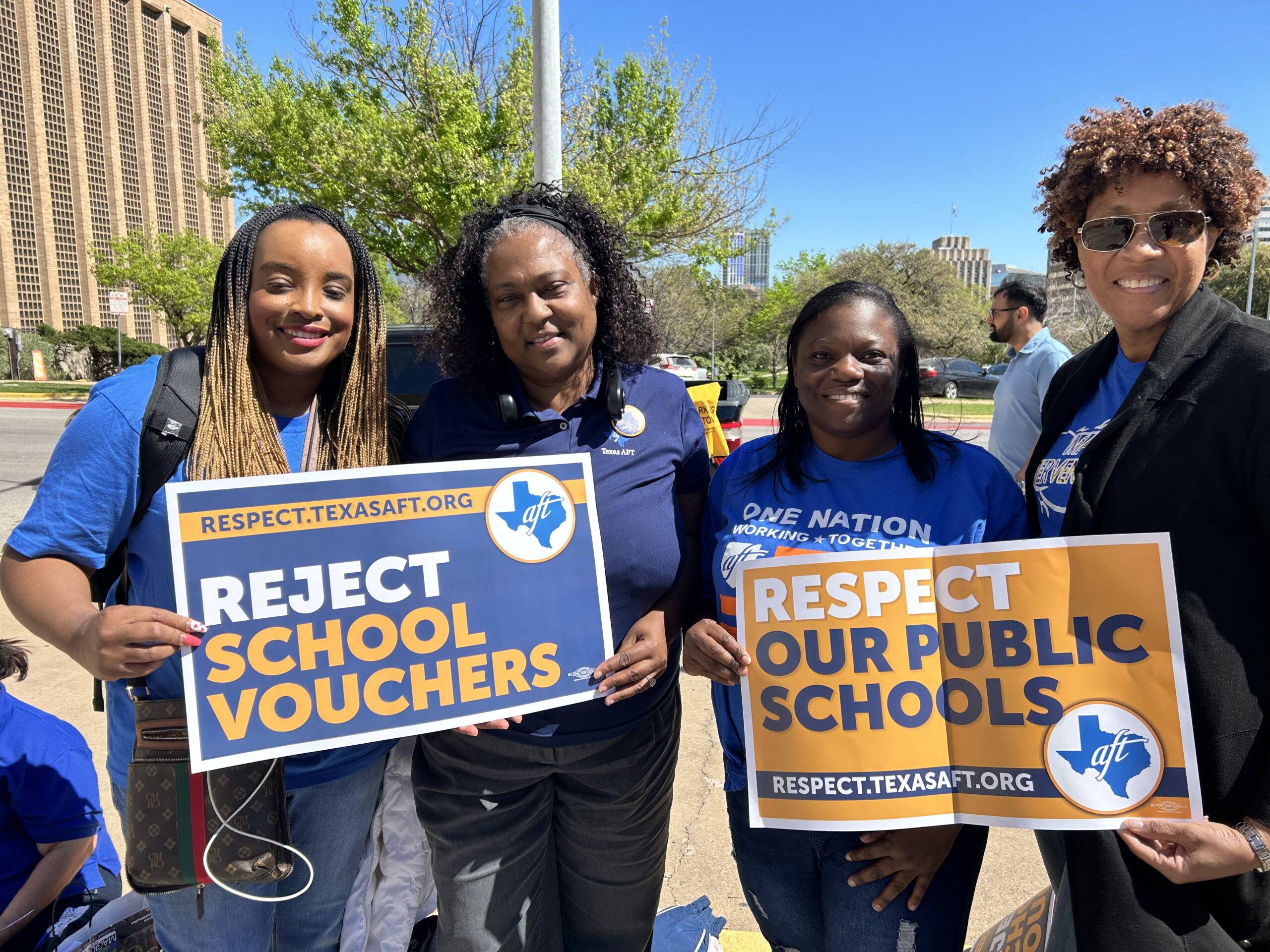

Above: A dissatisfied public school student at the Save Texas Schools rally.

This year, as we do every Thanksgiving, my brother-in-law Ryan and I traded war stories over a table laden with food and drink. Our front lines are in neither Iraq nor Afghanistan, but deep in the heart of Houston. Our stories are drawn from the stuff of our lives as teachers, soldiers in the education wars unfolding in the classrooms of our nation.

Ryan and I fight our battles in different theaters. I teach history at a university in Houston while Ryan teaches English at a nearby high school. Both of our respective institutions, of relatively recent birth and still busily inventing their school traditions, pride themselves on spanking-new football stadiums and high-tech classrooms. But this year, as in year’s past, our experiences were dramatically asymmetrical. When I confide my anxiety that I have fewer than 10 students in one of the two classes I teach twice a week, Ryan shares his relief that he has fewer than 30 in one of the six classes he teaches every day. After I express my impatience with students who do not read deeply, Ryan tells me about students who cannot read at all. When I have the ill grace to bemoan earning $30,000 a year less than the national average for full professors, Ryan smiles wanly, too gracious to reply that this gap represents more than two-thirds of his own yearly salary. While I worry about the mad spawning of administrators at my school, Ryan confesses his hope to become an administrator—if only to escape the grim impasse in which he finds himself.

Though he works 60 to 65 hours a week, he has barely any time to meet with his students, the ostensible beneficiaries of his labor.

Simply put, Ryan is in the trenches and I am not. Like many volunteers who rally to their nations’ colors in times of need, my brother-in-law was an idealist when he signed up. An indifferent student in high school, Ryan fell in love with literature at university; as a teacher, he hoped to reach students who resembled his younger, bored self. More than a decade on the front lines, however, has pulverized that idealism. Just as all war gives the lie to words like “honor,” “duty” and “sacrifice,” so too has teaching undermined Ryan’s belief that few professions are more honorable than teaching and his willingness to make financial sacrifices on behalf of duty to a literate citizenry. His experiences have trumped all of that. I do not know if it’s true that there are no atheists in foxholes, but I have good reason to believe there are few if any idealists still working in Ryan’s school.

How could there be? Take the example of 1914: Once that war of movement ossified into one of stasis, generals and politicians increasingly turned to technological breakthroughs to snap the stalemate. From poison gas to dirigibles, tanks to flamethrowers, one silver bullet after another was fired during World War I. Most were duds, and some were worse. Poison gas drifts over one’s own lines, tanks become firetraps and flamethrowers turn their users into Roman candles.

While no such horrors have been visited on Ryan and his colleagues, they are casualties nonetheless of the same kind of magical thinking. Like the mustachioed generals of yesteryear, Ryan’s school administrators insist that technology can win hearts and minds. To this end, Brian and his students were armed this year with Dell tablets. The administration’s ambition to go paperless, which carried a $17 million price tag, has turned into a fiasco worthy of the Battle of the Somme. Every day, Ryan teaches six classes, each of which runs 49 minutes. This race against time, thanks to the Dells, has become an obstacle course. Inevitably, students forgot to charge their tablets, or forgot to save their material or simply forgot to bring their tablets. Other students were plagued by software problems, while some of the more privileged, scornful of the Dells, refused to use them. After three months of mayhem and muddle, Ryan’s students have tabled the tablets and are again, like students in far more advanced Finland and Japan, using paper and pen.

The costs of technological magical thinking extend far beyond landscapes littered with torched tanks and darkened Dells. There is also our passionate attachment to standardized tests. In Texas, administrators cling to the STAAR—the State of Texas Assessment of Academic Readiness—with the same desperate conviction that Douglas Haig, Britain’s commander at the Somme, applied to Heavy Artillery Reserves (HAR). Just as the makers of munitions always emerge from war victorious, it is the corporate education complex and its legion of consultants who benefit most from these tests. Given that Pearson Education, the maker of STAAR, charges Texas taxpayers $90 million a year, is it surprising that Ryan must lead his students over the top and into the test? His students’ futures and his own rest on this test, and the twining is doubly tragic: Ryan risks his job if his students don’t test well, and his students risk missing the true rewards of reading and writing if they’re only taught to test well.

Just as all war gives the lie to words like “honor,” “duty” and “sacrifice,” so too has teaching undermined Ryan’s belief that few professions are more honorable than teaching and his willingness to make financial sacrifices on behalf of duty to a literate citizenry.

This massive investment has birthed a new literary genre in Texas—the 26-line STAAR essay, for which students are drilled relentlessly—at the expense of genres like the novel and drama. “Teaching the test,” Ryan told me, “comes at the cost of teaching literature.” Even the path to the test is mined with difficulties. All of Ryan’s classes include special-education students. The state rightly compels schools to mainstream these students, but in a cost-saving strategy about which many parents are unaware, nearly half of the students in some of Ryan’s classes have special needs. To attend to the dizzying array of needs in these classes requires daily miracles as great as that of the Battle of the Marne.

When Ryan is not careening through one class to the next, he is mired in paperwork, and here lies the true pity of his situation. Though he works 60 to 65 hours a week, he has barely any time to meet with his students, the ostensible beneficiaries of his labor.

But do we parents really care? Like family on the home front who find comfort in the official version of events—WWI gave us the modern spin on the word “propaganda”—we gaze at the facades of our schools and are reassured by the medals, like “Exemplary” and “Recognized,” they have earned. We turn our gaze elsewhere, convinced we are on the road to victory. But when I listen to Ryan, I cannot help but think that such victories may be no less Pyrrhic than those of 1918, or 1950, or 2003.