Progreso ISD Fights State Over Students’ Residency

A version of this story ran in the September 2015 issue.

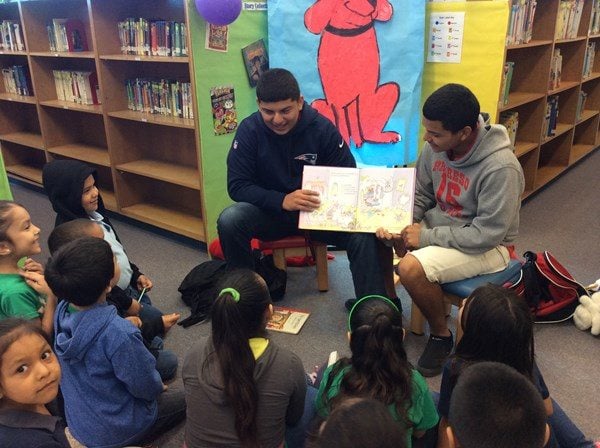

Above: Students at Progreso High School — "home of the Mighty Red Ants" — read to elementary schoolers in the district.

State investigators have wrapped a nearly two-year investigation into the Progreso Independent School District in South Texas, revealing a wealth of embarrassing financial shenanigans under former superintendent Fernando Castillo. Texas Education Agency investigators found evidence that Castillo, for instance, sold his used Chevrolet Silverado to the school district for $21,000 and tried to hide his involvement by funneling the cash through a district accountant. They say Castillo steered thousands of dollars of the school district’s money to his family and friends and charged more than $3,600 to a school credit card for meals in a five-month stretch. Now, citing a “widespread and systematic breakdown in the district’s governance,” the state has proposed dissolving Progreso’s school board and appointing a board of managers.

This report is the worst news yet for the beleaguered school system of around 2,000 students. It’s a vivid tapestry of a small district being systematically bled by profiteers from within. While most of the state’s allegations against the district turn on misappropriated money, there’s one long-running battle between the state and Progreso ISD that’s centered on students: a fight over how many of the kids in Progreso’s classrooms ought to be there.

That dispute — which isn’t mentioned in the state’s most recent report — dates to late 2013, when TEA investigators reviewing the school’s attendance records found 119 students on the rolls who, according to state officials, couldn’t prove they lived in Texas and probably commuted to the schools from Mexico. They said Progreso ISD had essentially overbilled the state for its attendance from fall 2011 to spring 2013; to clear up that little accounting issue, state officials said they’d go ahead and keep $1.8 million that otherwise would have been sent to the schools.

The attendance fight moved to the courts in March when the district sued TEA and Education Commissioner Michael Williams in Travis County. The schools claim state regulators relied on “hearsay allegations” about where the students lived and ignored records from home visits conducted by district staff. According to the school’s lawsuit, state investigators tracked some students as they crossed back and forth across the border to Nuevo Progreso before and after class.

Darren Gibson, the Austin attorney representing Progreso ISD, told the Observer that the district was able to provide documentation supporting residency claims for all but three or four students on the state’s list. “Some have parents who are longtime residents [of Texas]. They did everything they’re supposed to do,” he says.

Progreso ISD first attracted investigators’ attention in late 2013, when school board president Mikey Vela was arrested on federal bribery charges for orchestrating a massive pay-to-play scheme with his brother Omar, then the mayor of Progreso, and his father Lupe, then the school’s maintenance supervisor. After mounting their own investigation into the district, TEA discovered a litany of shoddy accounting practices, including bogus claims of perfect attendance at one school, and began questioning the district about its students’ residency soon after.

State law gives schools latitude to set their own standards for proof of residency in the district and in some cases allows schools to accept students who spend most of their time living in Mexico. In 2009, Del Rio schools superintendent Kelt Cooper launched an unpopular crackdown on students coming to his schools from Mexico (“Child X-ing,” December 2009), but today Progreso finds itself in the opposite position, arguing to keep students on its rolls despite questions about their residency. Gibson said he hasn’t found any record of the state cracking down on a border district like this. “It seems like Progreso has been singled out,” he said.

“Some have parents who are longtime residents [of Texas]. They did everything they’re supposed to do.”

The district’s suit raises a more basic question about the state’s actions: While state law requires districts to adopt a residency policy, it doesn’t dictate what the policy should be. Gibson says the state doesn’t have a right to withhold funding for students that the district has decided meet its residency standards — the same standards, the lawsuit notes, that more than 700 districts in the state also use.

The state has responded in court with a total denial of the district’s claims. A TEA spokeswoman declined to comment on the attendance dispute, as did new Progreso ISD superintendent Martin Cuellar.

Gibson says the timing of the state’s latest report and its threat to dissolve the school board is strange, given that the state’s allegations refer to two-year-old events and officials who’ve since been replaced, and that state-appointed conservators have overseen the district for more than a year. “If the TEA’s own employees thought that this district should’ve been running differently over the last year and a half, they should’ve said that,” Gibson says.

The most recent developments before the state released its report last month, Gibson says, were his own depositions of two TEA investigators. In his opinion, the depositions were fairly bruising to the state’s defense against the district’s lawsuit, and they were done just three days before the state threatened to take over Progreso ISD’s board. A state takeover could dramatically alter the course of the suit. Should a new board of managers replace the district’s elected board, Gibson says those state appointees would have the authority to drop the suit.

In the district’s court filings, Progreso ISD appears committed to educating the students on the state’s list as the case proceeds — beginning yet another school year with the TEA threatening to withhold the funding for their education.

Read Progreso ISD’s petition for declaratory judgment against the TEA below.