Now You See It

Artist Mel Chin revisits home in Houston.

–

by Michael Agresta

March 9, 2015

The poster for the original incarnation of Mel Chin’s career-retrospective exhibition, presented in New Orleans in February 2014, features two photographs of Chin: One shows a sexagenarian artist of international repute, the other a 13-year-old child of immigrant grocery store owners in Houston’s Fifth Ward. The images face off as if advertising a boxing duel. In between is the exhibition’s title:

RE

MATCH

Chin tells me the title reflects his approach to the retrospective, less as a celebration and more as “a marker to say, ‘We must move forward.’ Dylan-style, you know. Don’t look back.”

“I know she was an artist,” he adds, referencing the famous Bob Dylan lyric. “I’m an artist too, so it’s all good.”

That said, as Chin’s traveling rematch enters its third round (the second was St. Louis), “Don’t look back” is easier said than done. Houston is his hometown, the land of his birth, youth and emergence as an artist. Here, Chin faces off against not just his past self and work, but the city that made him who he is.

Trying to succinctly summarize Chin’s lifetime body of work is like trying to fit a grid to Houston’s famously unzoned sprawl. And yet here it is, on display for city dwellers to examine and make of what they will.

“Sometimes, because you have a history with a place, it’s almost like you have a little bit of apprehension,” he tells me over coffee and eggs the morning after his exhibition opened. For instance, he says, “There’s a history of segregation politics. … We lived in a city that might have had some of the worst brutality. You’re apprehensive because you’re bringing ideas that are counter to that, which I feel are options to the norm.” Chin says he has long felt welcomed by Houston’s art community, but he’s speaking of “the Houston beyond those already pre-attuned.”

Chin’s retrospective will dominate the Houston museum world for the next two months, with major exhibits at Blaffer Art Museum, Asia Society, Contemporary Arts Museum Houston and the Station Museum of Contemporary Art. There’s no comparison for it in terms of number of institutions involved since the Robert Rauschenberg retrospective in 1998. Trying to succinctly summarize Chin’s lifetime body of work is like trying to fit a grid to Houston’s famously unzoned sprawl. And yet here it is, on display for city dwellers to examine and make of what they will.

Much of Chin’s art is overtly political. He insists that all of it adheres to the essentially political practice of “researching to destroy preconceived notions,” though he can’t always predict if the end result will be explicitly political or not. He has worked in many genres. In the 1970s and ’80s he favored paint, ceramics and especially sculpture; then, in the ’90s, he eschewed object-making for installations and Joseph Beuys-style social interventions. In the new millennium, he has frequently returned to sculpture, along with animation and video game design. My favorite description of his work comes from Chin himself as he finishes his eggs, his hepcat twang just barely rising above the din of brunching Houstonians: “It’s almost like they’re incidents in confronting the delusion that accrues.”

Prominent examples of such incidents include Chin’s “Revival Field” (1990-97), a scientifically significant land-art project that has helped identify plants that can remove certain toxic metals from contaminated soil; “The Name of the Place” (1995-97), a collaboration with fellow artists and the producers of Melrose Place to embed socially progressive product placements and images in the props and sets of the TV soap opera; and “Operation Paydirt” (ongoing since 2006), a multistage “social sculpture” aimed at curtailing childhood lead poisoning in New Orleans’ most impoverished and crime-ridden neighborhoods.

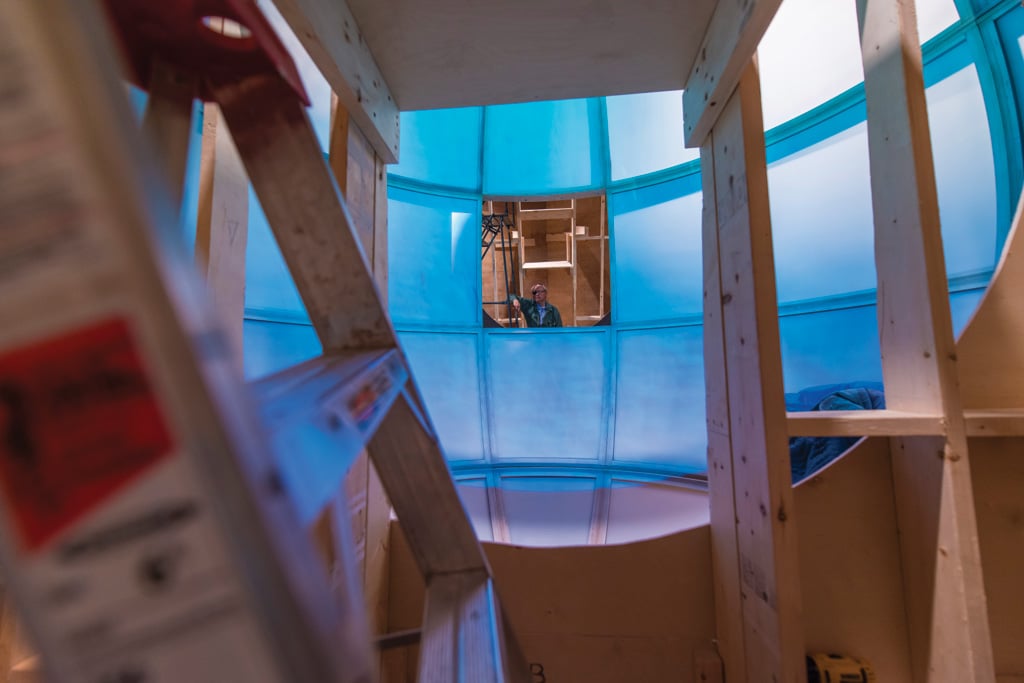

“Operation Paydirt” dominates Chin’s last 10 years of artistic practice. It includes several ongoing subprojects. “The Fundred Dollar Bill Project” invites schoolchildren and museumgoers alike to illustrate their own paper hundred-dollar bills. This artistic currency will eventually be hauled to Washington, D.C., where Chin will demand an equivalent dollar amount of government funding to remediate New Orleans’ soil. “Now You See It,” an educational animation on the dangers of lead poisoning, has shown on the Los Angeles public bus system, among other venues. “Sous Terre,” an armored truck for transporting fundred-dollar bills, has taken Chin’s show on the road across the country. “Safehouse” was a temporary art space and project headquarters in New Orleans designed as a bank vault, complete with a giant steel door mounted on a formerly derelict house.

In an introductory essay to Chin’s retrospective catalog, his friend and champion Andrei Codrescu puts the “confronting the delusion that accrues” concept another way, with special reference to the thread of environmental activism in Chin’s art. “If the future historian is a good one,” Codrescu writes, “he or she will be able to divine from Chin’s works the kind of toxins, both ecstatic and deadly, that the second half of the twentieth century distilled through human bodies and minds in order to reach the first half of the twenty-first century with a healing program for the future.”

Long before he became the sort of artist from whom one could attempt to piece together a “healing program for the future,” Chin was a mischievous preadolescent knocking around his parents’ store, Wholesome Foods Market, in Houston’s historically black Kashmere Gardens neighborhood. Young Chin preferred to work the meat counter because butcher paper could be repurposed for drawing. He also showed an early knack for sculpture, carving a memorial bust of John F. Kennedy out of meat soon after the president’s death in 1963. Customers were disturbed, and Chin’s father instructed him to stop making meat sculptures.

“It’s almost like they’re incidents in confronting the delusion that accrues.”

Chin remembers Clifton Chenier, the “King of Zydeco,” visiting the store to hang posters for an upcoming show. “It’s not always the art. It can be the wealth of what you’re living in,” Chin says when I ask how Houston shaped his work. “To go to the dance and see how fantastic and rare that is, to have original music and voices coming up. Maybe it’s a lesson about how we must diversify our experience at every opportunity.”

At age 14, just months after his parents moved the family to the suburbs, Chin experienced an unexplained psychological episode, entering an ambulatory catatonic state that would last for 13 months. His parents explored hospitalization but decided against it. Chin woke from his stupor to find he had lost three years of memory. He had to reteach himself to draw. (Before and after this episode, Chin attended after-school art classes at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.) Years later, as a 20-something just beginning to share his art with the public, Chin would exhibit a series of paintings titled “I Live in a Suburban Cell,” in which he re-imagined his parents’ living room as a padded cell in a psychiatric institution.

Chin left Houston for college, studying art at George Peabody College for Teachers in Nashville, Tennessee. Almost immediately upon his return, he submitted his “Western Dynasty Urns” (1974) to James Harithas, then curator of the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston. Chin had crafted the urns in college according to ancient Sung dynasty-era Chinese pottery techniques, adding the kitsch flourish of Texas longhorns. Chin proposed that the urns be buried underneath the museum for 100 years, where they might eventually revise the archeological record and situate the Chinese as aboriginal founders of Texas. Harithas didn’t bite on the urn proposal, but he did become Chin’s friend and one of his earliest collectors and champions. An urn from the series is finally on display at the museum as part of the current retrospective.

Chin took on odd jobs in the Houston art world. “I handled everything from Matisses to pieces by Goya, Titian and Warhol,” he has said. “I saw firsthand all the great art that came through Houston.” He also saw most of the homegrown art of the era after moving out of his parents’ garage and into the heart of Houston’s young creative culture. His reputation as an artist grew, too, and he began to earn commissions. In 1978, he installed (and by some accounts briefly lived inside of) “Manila Palm: An Oasis Secret,” a 50-foot-tall steel-and-fiberglass palm tree emerging from a pyramid that has stood sentry outside the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston ever since. It is the forward-looking museum’s only permanent installation.

Chin has written of his friendship with the grande dame of Houston art, Dominique de Menil, for whom he worked as an art handler in the early 1980s. When he nearly hit her with his car in the Rice Museum parking lot, driving drunk with his eyes closed, Menil took him aside and, instead of firing him, gave him a cryptic warning: “We must be vigilant!” Years later, in what Chin calls a “prodigal moment,” the museum bearing Menil’s name gave Chin a solo show in 1991. Chin, by then living in New York City, returned to Houston for the exhibit. He recalls Menil talking the day before his opening about “the difficult job of exposing the perps of unjust sufferings.” Then she stared at him, as she had a decade before, this time with sly pride in having helped him launch a career of socially responsible art-making, and repeated, “We must be vigilant!”

Chin had left Houston for New York in 1983, never to return as a full-time resident. Before he left, he was commissioned to create the canvas “Untitled (Terra Infirma).” That work, which Chin calls a “departure painting,” speaks to a reckoning with his hometown that would inform his later environmental activism. The enormous encaustic painting, currently hanging at Blaffer beside the “Safehouse” vault door, depicts a sickly bayou landscape populated by a pair of palm trees, a dark pool suggesting oil, and a building located on Allen Parkway that Chin found interesting. He tells me that an early version of the canvas featured a human figure: the “Sulking Lady” from a short story by Houston experimental writer Donald Barthelme. The “apprehensive creature,” as Chin calls her, was eventually removed and the landscape left to speak for itself. “I was observing the petrochemical history we’re all part of, watching it come crashing down in that period,” he tells me.

Indeed, by the mid-’80s Houston was in an oil-glut recession, but Chin was long gone, having set up shop on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Chin says his motivations for leaving Houston were philosophical: “My practice promotes extinction, sometimes of a certain lifestyle. Remove yourself from a social system, have a deep return to internal discourse.”

As for his current relationship with Houston, Chin says it’s defined both by roots and by entrenched systems he still wants to confront. “It’s not the heat. It’s the humanity,” he says, attributing the quote to songwriter Townes Van Zandt, another sometime Houstonian who had a complicated relationship to the city.

“The psychological weather of Houston, Texas, has been extreme, and the forecast remains the same,” Chin has written. “I have learned it’s not about ‘making it here’ (or anywhere), but ‘making it through’ with some empathy, some dignity, and some critical reason for being. That seems to be what matters.”

In Houston, I talked to several experts on Chin’s work and on the local art world, including retrospective curator Miranda Lash and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston curator of contemporary arts Alison de Lima Greene. Neither would go so far as to define Chin as a Houston artist, but both spoke of the importance of the city to his work and, conversely, of Chin’s importance to Houston, especially now that he is an artist of international stature.

“Mel has always been a beloved native son,” Lash told me at the Blaffer opening. “I think it took him going away to New York to be more recognized. This is a special moment for him. He’s now done projects all over the world, and people get a chance to see it and celebrate their own.”

Greene suggested that Chin’s sensibility has been shaped by Houston’s troubled racial history, including the violent police invasion of Texas Southern University campus in 1967 and the police murder of Joe Campos Torres in 1977. But Chin has rarely chosen Houston-specific incidents to protest or call attention to, especially after he left for New York. “When he did do images that were about outrage and torture and suppression, he did it on a world stage,” Greene said.

Many such images can be viewed at the Asia Society Texas Center and Contemporary Arts Museum portions of the retrospective. For instance, the monumental “Our Strange Flower of Democracy” (2005) replicates a 15,000-pound “Daisy Cutter” bomb in bamboo and coconut twine. The work references World War II Pacific Islander cargo cults that tried to lure U.S. military planes through sympathetic magic, not knowing what terrible gifts the planes could bestow. The video game “KNOWMAD” (1999) presciently contrasts the textile-based mnemonic traditions of central Asian tribes with the ultra-high-tech vehicles that increasingly police the region on behalf of world powers. Players sit at a driving simulator and race through various desert tents festooned with dazzling rug patterns, trying to find a MacGuffin. The sleek, phallic “Night Rap” (1994) responds to Rodney King’s beating by police and celebrates the hard-edged Los Angeles rap music that followed in its wake. The sculpture is a real policeman’s baton retrofitted as a directional microphone with an onyx hard-on for a handle.

“It’s not always the art. It can be the wealth of what you’re living in. … Maybe it’s a lesson about how we must diversify our experience at every opportunity.”

If there’s a fault to be found with Chin’s work, it’s that it’s too deeply based in obscure geopolitical conflicts, environmental crimes and historical trivia. Indeed, the Times-Picayune review of Chin’s New Orleans retrospective warned that the artist’s work “will appeal mostly to those museum goers who are able to answer Jeopardy $1000 questions before the television contestants do.”

This line of criticism is not entirely fair to Chin’s process. He has spoken and written in various venues of his practice as a “catalytic structure,” with research as the first and most necessary step. Over brunch he tells me, “It’s not about you as an artist changing the world. That’s disingenuous and probably not for real, and it’s silly and it’s not where you need to spend your time.” Instead, he says, “You need to understand that you have to do your homework and have a critical dynamic that’s going to enlarge the conversation to a degree where you are better informed.”

Such homework can take many forms. Sometimes it leads Chin down strange and obscure cul-de-sacs, like the time he measured the trajectory of shrapnel from cluster bombs to create jewelry mimicking those geometries on the human body (“Cluster,” 2005-6). Such works are intellectually demanding, and to view so many side by side in a retrospective can overwhelm. Just as often, however, Chin’s works do the opposite, offering stunning clarity. Many of his simplest-looking works contain whole histories of inequity, not to mention hours or years of sincere striving for solutions and new ways of thinking.

For instance, he foresees the final, museum-ready form of “Operation Paydirt” as nothing more than “a single clean drop of blood from a child no longer suffering from lead poisoning.”

Similarly, despite the vast breadth of Chin’s work, it’s easy for any museumgoer to see which pieces are coming to define his legacy. These are on display at Blaffer, and run in a direct line from “Untitled (Terra Infirma)” through “Revival Field” and into the ongoing magnum opus “Operation Paydirt.”

The “Terra Infirma” canvas, painted when Chin was 30 years old, defines the content of this thematic thread, what he calls his “dark world perspective” of ongoing environmental and social crises that make life on earth miserable and, for some, impossible. The painting remains the work of a young artist, however. Chin’s mature practice—the work for which he is best known and which has brought him international acclaim—began eight years later, in 1989, after his first major solo show at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., when Chin decided to stop making art objects. That same year, he began work on “Revival Field.”

It’s hard to conceive today just how outside the art world mainstream “Revival Field” was in the early 1990s. Even the famous earthworks of the 1970s, such as Robert Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty,” had been focused on making an aesthetic imprint on the surface of the Earth, not a holistic remediation of the Earth’s invisible contents. John Frohnmayer, the chairman of the National Endowment of the Arts (NEA) at the time, personally withdrew a grant the NEA had made to Chin to support the work. The NEA informed Chin that Frohnmayer was “not persuaded … that the artistic aims as outlined in the application were sufficient to merit arts endowment funding.” In other words, Chin’s proposal was either too political or not sufficiently aesthetic to merit funding under the George H.W. Bush administration.

“[Frohnmayer] was trying to define art as a beautifully crafted object,” Greene tells me. “But art ended up developing in a very different direction. Mel was not the first, but he became the lightning rod for that necessary moment of change.” Thanks in part to vociferous support from artist organizations and museum directors nationwide, including Suzanne Delehanty of the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Chin was able to convince Frohnmayer to undo his veto. The only stipulation was that Chin better define the “aesthetics of the earthwork.” These attempts to reconcile his “social sculpture” vision with the museum- and gallery-based tradition, including drawings, diagrams and dioramas, can be seen on the walls of Blaffer in the current exhibition.

It remains to be seen if “Operation Paydirt”—the website of which defines its mission as nothing less than “to imagine, express and actualize a future free of childhood lead poisoning”—will be as successful as the more modest “Revival Field.” But through “Safehouse,” “The Fundred Dollar Bill Project,” “Now You See It,” “Sous Terre” and other subprojects, Chin has mobilized entire communities around his catalytic vision. That, to Chin, is a worthy end in itself.

“They are the artists. They’re the voice that is finally respected,” Chin says of the schoolchildren and museumgoers who provide much of the artistic production of “Operation Paydirt.”

“It’s not about me making change. I’m most overjoyed when we’re traveling in that armored truck, when we pick up a 9-year-old child who’s concerned about what he could do to protect himself from an environmental toxin and felt like he actually did something to respond to it. Because before, he thought he couldn’t do anything.”

It’s fitting that this exhibition began in New Orleans. More perhaps than any other city in America, New Orleans has had to confront man-made and racially biased environmental catastrophes head-on. Houston has been spared the worst, so far.

“It wasn’t at all coincidence that I had a very keen interest in Mel because of where I was and what my city was going through,” Lash said when I asked about her decision to curate the Chin retrospective. “Katrina, like the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan, makes you think: What is the role of art in all of this? These are desperate situations. Why do we still fight for art? Why do we care about art? Why is art important?”

Chin’s work is poised to grow more resonant as we move deeper into this troubled century. The issues that drive him, from racial crimes to environmental inequities, have often been as invisible to the art world as metal contaminants in ghetto soils. Through Chin’s work, as through the growing spate of 21st-century environmental disasters, we begin to see it.

As for the specific case of Houston, however, Chin allows himself a bit of optimism. The “rematch,” he tells me, has ended in a favorable decision. “I was kind of relieved,” he says. “There is a support for my methodology, the complexity of my case. There’s actually a surprise of how this city has turned into one of the most diverse and open cities, I think, in the country.”

“It’s kind of changed,” he adds. “Sometimes you just live long enough, you get ready to change again. That’s what it feels like. It’s a lesson to me.”