Lawrence Goodwyn, A Man of Words and Ideals

Remembering Larry Goodwyn—reporter, historian and champion for civil rights and populism.

A version of this story ran in the November 2013 issue.

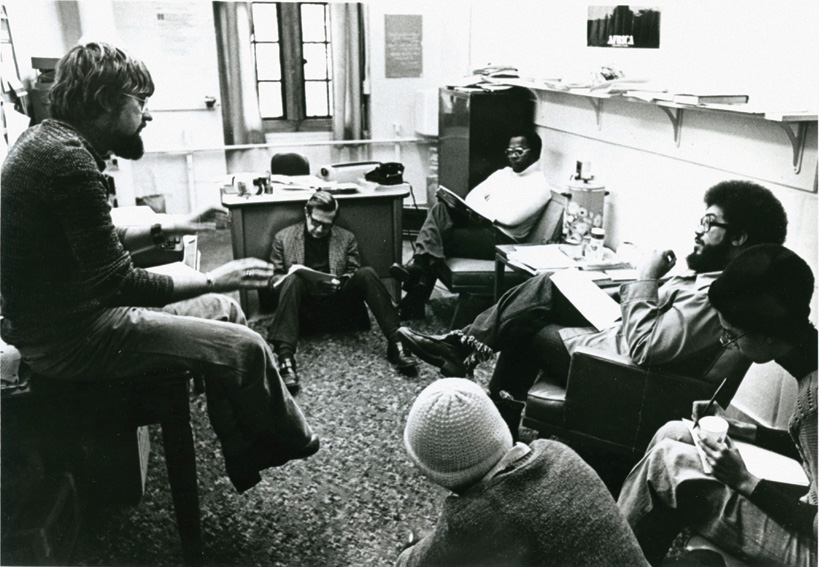

Above: Lawrence Goodwyn, sitting on the floor, during interviews for Duke University’s oral history project in the mid-1970s.

Lawrence Goodwyn, the celebrated, controversial author of the definitive history of south-midwestern late-19th-century American populism, and an important editor and writer for The Texas Observer for decades, died at 85 of long-suffered emphysema at home with his family in Durham, North Carolina, on Sept. 29. He taught history for 32 years at Duke University, where the flag was at half mast upon his death. A memorial is scheduled for him at Duke on Nov. 9.

His scholarly work about the Farmers Alliance of the 1880s and 1890s, Democratic Promise: The Populist Moment in America, published in 1976, was shortlisted for the National Book Award and has been a standard textbook ever since in many universities’ classes. In this book (and in a shortened version, The Populist Moment, in 1978), Goodwyn recounted and analyzed the radical revolt of U.S. farmers, starting in Texas, against railroads and banks in the Northeast. The farmers, converging in nonviolent rebellion, sought to devise their own banking system, broke white racist tradition in their political cooperation with blacks, and succeeded in electoral politics to an extent until they dissolved back into the Democrats in 1896.

Later in his life, in 1991, again in a controversial book, Goodwyn analyzed the vital theories and actions of the workers in Gdansk in Solidarity, the historic revolt against communism in Poland that tipped off the domino-like collapse of the Soviet empire.

Goodwyn’s lifelong societal passion was the cause of black people in the United States as victims of slavery, and subsequently of social and economic oppression. After his period as an editor and essayist with the Observer in the late 1950s, he became a principal staffer with Ralph Yarborough as Yarborough juggernauted through several Texas campaigns into the U.S. Senate. Meantime, Goodwyn was one of the theorists and leaders of the Democratic Coalition, comprised of blacks, Hispanics, unions, and white liberals in Texas, whose candidate for governor, Don Yarborough, was neck and neck in the prospective 1964 race on the day the incumbent, John Connally, was shot in the car with John F. Kennedy in Dallas, an event that assured Connally’s re-election and also ended the big-city-based liberal political revolt of that period in Texas.

“By word and deed, Goodwyn rewrote the textbook story of our nation by focusing on the enormous potential of grassroots people,” said Jim Hightower, former Texas Agriculture Commissioner, former editor of the Observer and publisher of the populist Hightower Lowdown. “He revealed that real progress comes from the mavericks and mutts who dare to challenge ‘the great men.’ From his muckraking days as a fiery editor of The Texas Observer, and then as a passionate organizer for the civil rights movement, he didn’t just read history, he experienced and practiced it on dangerous turf.”

Goodwyn mentored, among many others, Ernesto Cortes when Cortes was an upcoming social champion of the Latino poor.

Young Ernie, emerging from helping poor people in the St. John’s slum in North Austin, went door to door through the Mexican-American West Side of San Antonio, talking with about a thousand people, making notes on three-by-five cards, and then organized those people as “COPS,” Communities Organized for Public Service, the neighborhood-based political-pressure powerhouse that was a model for such assemblies of the poor in other U.S. cities and to this day commands the attendance and concessions of elected officials.

Now 70 and national co-director of the late Saul Alinsky’s Industrial Areas Foundation, Cortes has spent his life organizing and mentoring leaders among the poor on behalf of needs and causes specified by the poor themselves so that “it’s their thing, not your thing,” as he told me recently. He expressed “my great debt” to Goodwyn, for teaching him how to overcome “the culture of deference and acquiescence.”

“He was a deep, good friend, important to me before I decided what I wanted to do,” Cortes said. Goodwyn helped him to read critically and thoughtfully. While urging Cortes to be sharp and tough for social justice, Goodwyn also told him, “never lose your love words, your capacity for tenderness, your capacity to care about other people.” Cortes granted that Goodwyn could be irascible, “but I regard that as endearing. I am forever in his debt.”

Dr. Max Krochmal, a student of Goodwyn’s at Duke and now assistant professor of history at Texas Christian University and Summerlee Fellow in Texas History at Southern Methodist University, said Goodwyn was a man “frequently way ahead of his time,” whose importance as a historian followed from his assiduousness as a reporter. “He had a unique ability to examine current events, dig to the bottom and locate their origins, and speculate in a remarkably prescient manner about their often vast implications.”

Former Observer editor Lou Dubose, now editor of The Washington Spectator, was taken by Goodwyn’s idea of a “democratic conversation where every party has to have the freedom to participate as an equal.” Most of Dubose’s serious conversations with Goodwyn over the years, he said, were catalytic—“one of his finely honed ideas would transform the way I thought about a subject.” Goodwyn once told him about a transformative moment during the attempt of a young white organizer and three black women, one in her 80s, to register to vote in Mississippi. As they got out of a car and walked to the courthouse, Goodwyn remembered, the black women’s courage in the face of oppression and their “understanding of the ways of the white man” somehow transformed the young organizer, himself, for his future work.

When Larry was 15 and I 14, we bonded playing pool in a bookie parlor in the basement of a building across the street from the San Antonio Express. We were sports writers on the paper while the grown men were away killing and dying in World War II. Now and again we made small illegal bets down there with the boss of the place, who was named Travis, on the far-away horseraces. Betting dimes and quarters against each other at the raised edges of the green velvet, we got so good we felt like sharks. He was a little better than me, but in a spell of them I could skin him a game or two.

Born in 1928 in Arizona where his father, an Army colonel, was posted, Larry majored in English at Texas A&M, was himself a captain in the Army in the Korean War and then worked in the oilfields in Texas. When his wife of 55 years, Nell DeReese, told him one day that she had registered him in the Ph.D. program at the University of Texas at Austin, he said OK and went ahead and earned it. He turned up for the second time in my life in the second half of the 1950s when I hired him as one of my series of associate editors at the Observer.

Covering the Legislature, Goodwyn concentrated on the domination of Texas politics by the oil industry. Dr. Krochmal, re-reading the Observer issues for a book on Texas political and societal history during that era, recalls a few of Goodwyn’s pieces in the 1960s “that demonstrate his ability to see beyond the day-to-day story and look ahead.”

In one entitled “New Shapes in Texas Politics” after the 1962 general election, Goodwyn saw and analyzed “the dramatic shift of conservative Democrats into the Republican Party,” while observing that the civil rights movement was quickening in still-racist Texas. He argued that white liberals needed to catch up and commit to complete racial integration. The next year, Goodwyn wrote a seminal report on La Raza Unida, the militant Chicano movement in the tiny Texas town of Crystal City, entitled “Los Cinco Candidatos.” In 1965, Krochmal recalls, Goodwyn and another 25 white liberals supported a student-led civil rights movement in Huntsville and were arrested.

“Finally, in Larry’s Dec. 31, 1965, piece, ‘The Caste System and the Righteousness Barrier,’” Krochmal observes, Goodwyn argued “that white liberals carried what has later been called ‘an invisible knapsack’ of power, privilege, and, in his words, ‘unconscious white supremacy,’” a problem “not one of maliciousness, but a divide between ‘the politics of the future’ and ‘the politics of the present.’” Participants in the latter sought to win the next election, while adherents to the former wanted to destroy the caste system. And at a more fundamental level, Goodwyn had continued, black and white activists did not know how to talk to one another and shied away from candid conversations in interracial crowds, uttering “polite banalities to avoid speaking difficult truths lying by omission,” the white liberals not understanding that blacks could be the new leaders.

In 1971, Goodwyn published in the American Historical Review a remarkable realization of his blended reportorial skills and historical scholarship, exhibiting as well his uncompromising militancy against white domination of black people in U.S. history. This was his report and essay, “Populist Dreams and Negro Rights: East Texas as a Case Study,” which focused in detail on the victories of a local of the People’s Party (the political arm of the Farmers’ Alliance) in Grimes County, 60 miles northwest of Houston, throughout the 1890s. Goodwyn reports that an estimated 30 percent of Anglos in the county teamed up with the majority of black voters to win local elections through that decade. But then, in 1900, there were outright murders of some of the allied whites and blacks, and after a formal threat and a large armed rally of the White Man’s Union that had formed in reaction, “a black exodus began by train, by horse and cart, by day and by night.” The governing black-with-white coalition was bulleted, shotgunned, and then threatened out of the county, and in the ensuing election, the People’s Party local was smashed and “that part of the constituency that was black” was eliminated.

“Populists in East Texas and across the South—white as well as black—died during the terrorism that preceded formal disfranchisement,” Goodwyn wrote in this paper.

“[M]uch of the Realpolitik of the South, from Reconstruction to the modern civil rights movement, rests on legal institutions that, in turn, rest on extralegal methods of intimidation.” What was needed, he concluded, was oral history from the memories of the blacks oppressed and suppressed. Goodwyn said to Max Krochmal, his former student remembers, that they would “explore how Southern history was written by a monoracial base of sources, with memoirs of Democrats who had slaughtered their opposition, and the least we can do as historians is gather the oral histories of blacks.”

At Duke the year his paper on Grimes County appeared, with the backing of North Carolina Gov. Terry Sanford and $250,000 from the Rockefeller Foundation, Goodwyn and senior colleagues founded the university’s Oral History Program, through which students, a majority of them black, according to the Duke Department of History, have “helped transform the way civil rights history is written in America” and is taught in universities. The director of Duke’s Center for Documentary Studies, Wesley Hogan, said that although “most of us have been culturally organized by society not to rebel,” Goodwyn’s work “encouraged us to dream democracy anew” by showing that “farmers, steelworkers, day laborers, and sharecroppers found stunning new ways to act democratically.”

Goodwyn, along his way at Duke, helped lead a successful campaign to keep the Nixon presidential library from being established there. Duke history professor Bill Chafe, with whom Goodwyn set up the school’s Center for the Study of Civil Rights and Race Relations, said Goodwyn was “always challenging, provocative, and sometimes abrasive,” and always said “the way we’ve been taught history is crap and we need to reconceptualize the whole way democracy works.”

The next-to-last time I talked with Larry, six or eight months ago, I passed a remark or two critical of President Obama and was buzzsawed from the other end of the line. Larry was a ferocious champion of our first black president. Although in the spirit of our long friendship, I rang off rather quickly. When I phoned him back a month or two later, we both avoided the subject, talking together happily an hour or two about ourselves, about his and Nell’s biology-teacher daughter Lauren and son Wade, who is a national correspondent for NPR, about my family, too, and anything else under the beclouded sun. Both times, though, I could hear on the phone that he was having real trouble breathing, and I made note in my mind to go over there for some time with him before he died, but I didn’t.

He is no longer here to contend sharply when challenged or irked. But in Democratic Promise, in The Populist Moment, and in his other best work, Larry Goodwyn will go on speaking for himself and for others long after his death.