How Texas Failed to Catch a Geography Textbook’s Glaring Slavery Error

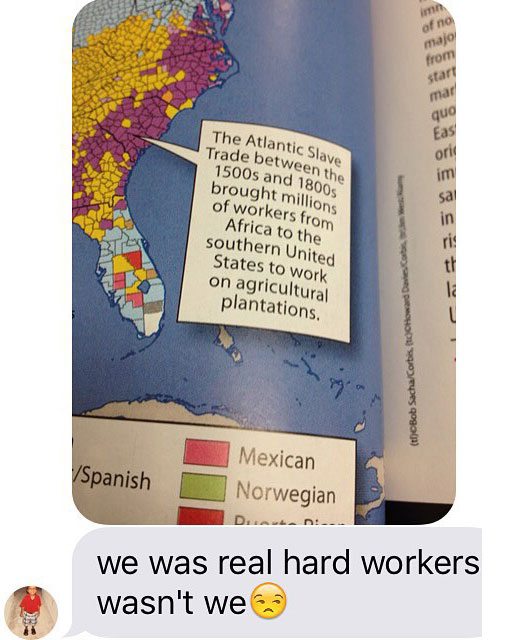

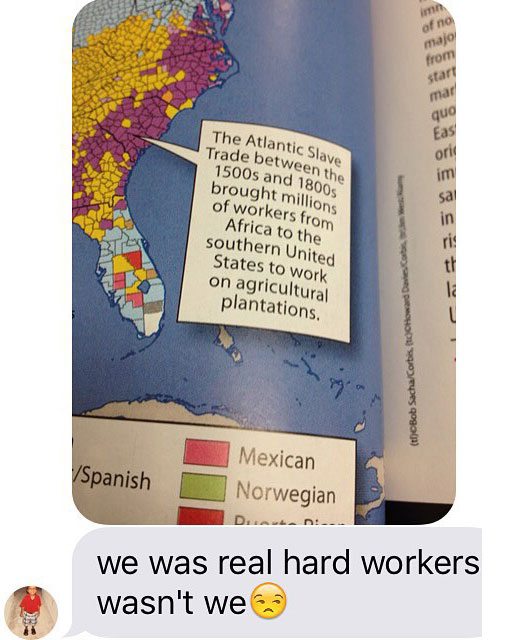

Above: Roni Dean-Burren's son, Coby Burren, sent her this message after reading a passage in his McGraw-Hill World Geography book.

A University of Houston doctoral student and former English teacher has sparked a national conversation about how public schools teach geography, history and race after suggesting a correction to her son’s world geography textbook.

In a video Roni Dean-Burren posted to Facebook on October 1, Dean-Burren says her son Coby Burren, a student at Pearland High School, first pointed out a page in his book under the heading “patterns of immigration.” It included some seriously inaccurate phrasing:

“The Atlantic Slave Trade between the 1500s and 1800s brought millions of workers from Africa to the southern United States to work on agricultural plantations.”

Burren texted his mother an emoji-accented photo of the page, adding [sic]: “we was real hard workers, wasn’t we.”

The word “slaves” — so clear, so accurate — was right there, but an author chose “workers” instead, and even after months of textbook reviews, it seems nobody thought to change it. At the start of her video, Dean-Burren lingers for a moment on the book’s first few pages, which list dozens of authors and reviewers hired by the book’s publisher McGraw-Hill — “All of these people who are seemingly wise people, all of them have that little ‘Ph.D.’ behind their name,” Dean-Burren notes — who signed off on that passage.

Many of you asked about my son's textbook. Here it is. Erasure is real y'all!!! Teach your children the truth!!!#blacklivesmatter

Posted by Roni Dean-Burren on Thursday, October 1, 2015

Her video, and a separate image with the wording in the textbook, spread fast and generated a swift response. A day after her video went up, McGraw-Hill Education posted a mea culpa, also on Facebook, agreeing that the book’s original language was mistaken and pledging to update the book online and in future printings. “We can do better,” the post said.

The passage from the book has become national news today, steeped in a larger conversation about how Americans talk about race, whose history gets taught in schools, and how those decisions shape the country we’ve become and will become. As Dean-Burren — who is pursuing her doctorate degree in education — put it in a caption below her video, “Erasure is real y’all!!! Teach your children the truth!!! #blacklivesmatter.”

Earlier this summer, Dean-Burren proposed a discussion at next year’s SXSWedu conference about how the Black Lives Matter movement is taught in schools. (And if that suggestion hadn’t caught organizers’ attention before, they’re probably listening now.)

But there’s a separate thread to this story, which is Texas’ shameful tradition of turning the state’s curriculum-writing and textbook-review processes into fierce culture war battlegrounds. This fall, public school students are also being taught from new books that downplay the harm of segregation and minimize slavery’s role in the Civil War.

Those lessons are the product of years of politicking around the truth at the State Board of Education. So are the subtler ways in which the state curriculum encourages children to question global warming and evolution, or not to consider Native American history or the LGBT rights movement much at all.

But the state curriculum doesn’t describe victims of the trans-Atlantic slave trade as “workers.” Nor was that page in McGraw-Hill’s World Geography the subject of debate during last year’s messy, drawn-out fight over new social studies texts. The language Cody Burren found in his textbook is the result of something else — it’s what we get when the state’s official review is too busy shoehorning the cast of the Old Testament into U.S. history to pay attention to much else.

“They do not do a thorough job,” said Dan Quinn, a spokesman with Texas Freedom Network, which tracks conservative efforts to introduce biased or inaccurate language into the textbooks. “That’s of course been the problem from the beginning. The State Board of Education does very little review of the textbooks. … The ability and the will is there if they want to do it, but they’ve created such a mucked-up process that it’s almost impossible for them to do an in-depth review.”

Quinn has observed the state’s textbook review in action, over the course of one week at an Austin hotel, with three to four people assigned to each text. The qualifications required to serve on the review panels might surprise you. State Board of Education members, who are elected in partisan races, often use nominations to these review panels as political favors or chances to cement their own conservative bona fides. Two Republican board members nominated David Barton — who rose to prominence by recasting American history in evangelical terms — to review the state’s standards in 2009, and former SBOE chair Barbara Cargill volunteered now-state representative and then-used-car-dealer-and-pastor Mark Keough to review the U.S. history books last year.

You can review the books for the state even without serving on the panel, and in fact, last year was a record year for citizen participation. In a single week last fall, the state board got over 1,500 emails about the books before it voted on them. Most of that correspondence was driven by a new group called Truth in Texas Textbooks, which concerned itself mostly with ensuring that the books were sufficiently pro-Christian and anti-Muslim. That group was critical of McGraw-Hill’s World Geography, calling it “so flawed that it is not recommended for adoption,” mostly for its supposed “agenda-based Islamist revisionism of the history of Israel.”

The passage from the book has become national news today, steeped in a larger conversation about how Americans talk about race, whose history gets taught in schools, and how those decisions shape the country we’ve become and will become.

Quinn told the Observer that last week was the first time he’d seen the infographic on “workers” brought to the United States in the slave trade. His group’s reviewers, who also read McGraw-Hill’s World Geography, also missed the book’s use of the word “workers” instead of “slaves,” a failure he attributes to having limited resources for such a monstrous task. With many books to review at once, he says TFN focused its World Geography review on the particular hot-button issues of climate science and religion, enlisting experts to provide narrow critiques.

In other words, the few people who took the time to read the book before it was approved were entirely focused on a handful of narrow political questions, and the book’s treatment of slavery was not among them.

Of course, the language is in the book in the first place because someone — many people, really — at McGraw-Hill screwed up. In an email to employees and members of the press on Monday, McGraw-Hill Education CEO and President David Levin admitted as much, saying he is “deeply sorry that the caption was written this way. While the book was reviewed by many people inside and outside the company, and was made available for public review, no one raised concerns about the caption. Yet, clearly, something went wrong and we must and will do better.” Levin pledged that new internal controls would be coming, along with greater diversity among the company’s textbook reviewers.

“They should be criticized,” Quinn said, “but we should also keep in mind that human beings make some mistakes sometimes. … It could have been found way earlier in the review process if the state had a review process that actually made sense. This is a perfect example of how the state board isn’t exactly telling taxpayers the truth when they say they’re doing such a thorough review of the textbooks. It’s a fraud.”

By failing to correct the passage before McGraw-Hill’s World Geography was printed and shipped to schools across the state, the company and the state ensured that students will be learning from books that downplay the violence of the slave trade for years to come. Dean-Burren has noted that for all of their apologies, McGraw-Hill officials stopped short of replacing the books with corrected versions.

“They can recall those books,” she told the Washington Post. “Regardless of whether you’re left-leaning or right-leaning, you know that’s not really the story of slavery.”