That Sinking Feeling

Is indicted Attorney General Ken Paxton a political aberration or a symptom of a larger sickness?

A version of this story ran in the September 2015 issue.

On a muggy summer night outside the fortress-like Cottonwood Creek Baptist Church in North Texas, Valerie Herrington, a member of the McKinney Tea Party, wants the world to know she’s made up her mind about Attorney General Ken Paxton’s legal difficulties, which seem, at the moment, to be multiplying. “There’s nothing to it,” she says disgustedly. “It’s a witch hunt.” How does she figure? “I know Ken Paxton. He’s a good man. And I also know that there’s witch hunts going on in Austin. So I know it’s a witch hunt.” With that, she ambles off into the darkness.

Earlier that day, July 28, a grand jury at the nearby Collin County Courthouse had added two first-degree felony charges to a third-degree felony charge issued against Paxton earlier in July. The three sealed indictments alleged that Paxton committed securities fraud and failed to register as an investment advisor. On Aug. 3, the indictments became public, and Paxton was booked at the courthouse, slipping in and out of a back entrance via black SUV. He had marked a new milestone in his audacious career as a public servant, becoming the third of the last five Texas attorneys general to be indicted on criminal charges. He now faces the possibility of conviction and disbarment. Given the dearth of support he’s received from his fellow statewide officials, he may be pressured to resign before his first term is up in 2018. Over the last few months, the headlines have been growing more ominous for Paxton, and talk in Austin has turned to whom Governor Greg Abbott might appoint to replace him. Regardless of what happens, he’s still poised to become the first of the Texas tea party heroes to fall from grace.

McKinney’s proudest son is in serious peril, and the questions raised by his case implicate local officials and prominent citizens of Collin County. But inside Cottonwood Creek, the attention of the McKinney Tea Party is on distant horizons. Standing in front of Sunday school ephemera and a tropical beach backdrop made from brightly colored paper, a doctor gives a presentation on the evils of marijuana. Later, a square-jawed candidate for sheriff rises to speak about his 2014 trip to the Rio Grande Valley, showing the crowd videos of helicopter, boat and car chases while members of the audience ask incredulously why authorities aren’t using more lethal force.

Tea party activists like these helped turn Paxton from a middle-of-the-pack state representative into an up-and-comer with a magic touch whose rise to statewide office seemed almost foreordained. They are citizens who claim to loathe dishonesty, corruption and business-as-usual politics above all else, and their loyalty to Paxton insulated him as his moneymaking schemes grew more and more audacious and his public persona became less and less sincere. Paxton learned early how to earn and keep their respect, allying with their favored groups and adopting their dogma as his own. The respect of the tea party faithful has sustained him and, despite the indictments, the love many feel for him is undimmed.

It must be a strange time to be Ken Paxton. He has been facing the prospect of felony charges for nearly a year and a half, even as he floated effortlessly to victory in the 2014 Republican primary and general election. It is a strange time, too, to be a citizen of Texas, and thus implicated in the question of how such a manifestly compromised figure could become the state’s top law enforcement officer. Paxton’s rapid ascent from state representative to state senator and then to the attorney general’s office in the span of just three years has been an object lesson in the dysfunctions of contemporary Texas politics. Voters had every opportunity to see him for what he is, and still he succeeded.

Ken Paxton may eventually fall and fade. But the scaffolding that lifted him to the upper echelons of state government remains in place. As the effort to prosecute him builds, media and public attention will focus on the particulars of his case. But the most pressing question posed by Paxton’s example won’t be resolved in court. It’s this: How do we end up with men like Ken?

There are two parts to the case against Paxton, which will be tried by special prosecutors Kent Schaffer and Brian Wice in Fort Worth. The third-degree felony charge relates to behavior Paxton has already admitted: Beginning in 2004, and as recently as 2012, Paxton funneled his legal clients to an investor friend named Frederick Mowery, who kicked back a commission to Paxton. He didn’t tell his clients he was benefiting from the deal, as any reasonable sense of ethics would dictate, and he didn’t register with the Texas State Securities Board, as the law mandates.

The two first-degree felony charges relate to similar behavior, on a larger scale, alleged to have taken place in 2011. In those charges, Paxton is accused of helping induce investors to buy into a tech company named Servergy Inc., which is currently the target of a federal investigation. In that case as well, Paxton allegedly got a cut for referrals. The charges allege that he failed to disclose his role in the deal to two investors, one of whom is state Representative Byron Cook. The indictments hint at a broader narrative about Paxton: Soon after he won public office in 2002, he began to involve himself with business ventures that skirted the line between propriety and impropriety, and sometimes crossed it. As time went on and he failed to suffer political or legal consequences, he grew more brazen.

When Paxton was elected to the Texas House in 2002, his yearly personal financial disclosure form was essentially a blank slate, listing little more than a membership with the Collin County Bar Association.

By 2011, he was reporting a stake in 28 companies and a variety of other investments. Paxton’s prominence in Collin County provided him opportunities and connections, and as the years went on, he took advantage. A full accounting of Paxton’s business history would require an article much longer than this one, but a number of instances that raise serious questions about Paxton’s judgment have already been public for some time.

Take the 2004 case in which Paxton and a coalition of investors — one of whom was Paxton’s friend Greg Willis, who became Collin County’s district attorney in 2010 — purchased two plots of undeveloped land on Eldorado Parkway, in eastern McKinney, for some $700,000. The land was quickly rezoned by a city board, whose vice chairman Don Day, was a friend of Paxton’s. The rezoning opened up the area for development, and a small portion of the land was sold to Cornerstone Development Corporation, a Dallas real estate company, for $1 million. That site later became the offices of the Collin Central Appraisal District.

Then there’s Paxton’s investment in WatchGuard, an Allen company that hoped to meet local and state governments’ growing demand for police dashboard cameras. The company seemed to be aware of the benefit that government connections could provide when it advertised to potential investors. As the Associated Press first reported in 2008, company documents made sure to emphasize that WatchGuard was “privately funded and closely held by an influential shareholder group that includes three state representatives,” including Cook, who was elected to the Legislature the same year as Paxton, and had invested in property with him in central and north Texas. (The two men invested in a number of ventures together before the relationship turned sour over the Servergy deal, and Cook became a complainant in one of Paxton’s felony charges.)

In 2006, the Texas Department of Public Safety selected WatchGuard to outfit the agency’s fleet; the selection followed a bidding process that one of the company’s competitors charged in a letter to a state agency was designed from the start to select WatchGuard. Paxton and Cook later voted for a state budget that funded WatchGuard’s new contract. As WatchGuard’s prominence and profits rose, Paxton and Cook sold some of their stock in the company. Paxton told the AP in 2008 he’d owned only a small part of the firm, but WatchGuard’s CEO claimed that Paxton was a personal friend and original investor whose ownership stake was “not insignificant.”

The Texas Constitution bars legislators from benefitting “directly or indirectly” from contracts authorized by the Legislature. But Paxton told the news agency that the WatchGuard contract, in the context of the state budget he voted for, was as insubstantial as a “flea on an elephant.” Paxton also asserted he “didn’t even know [WatchGuard] had contracts with the state of Texas,” but even after confirmation that it did, he maintained an investment in the company. As of his latest available personal financial disclosure form in 2014, he continues to own an interest.

The problem with the WatchGuard cameras is that they didn’t match up to the competition, according to Aaron Smith, a Navy veteran and engineer who oversaw the McKinney police fleet. An officer with the department for 12 years, he said he got a directive from the police chief: The city would rip out its patrol fleet’s well-performing Panasonic cameras and replace them with WatchGuard models. Smith says the WatchGuard cameras failed frequently and featured much weaker safeguards against unauthorized editing of footage. The whole thing weighed on Smith’s conscience so much that he left the force in December 2013.

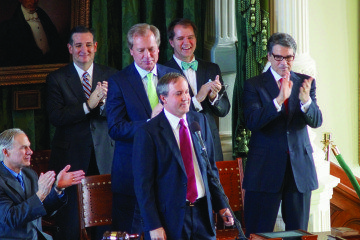

His inauguration was attended by a who’s who of Republican VIPs. Perry, Abbott, Cruz, Dewhurst, Patrick and Texas Supreme Court Justice Don Willett came to speak to an audience packed with notables.

Ken Paxton is not the first state representative to discover that the prominence of public office can deliver benefits in the private sector. But he continued to engage in business activities that exposed him to accusations of conflicts of interest even as he plotted running for higher office.

Consider the McKinney Economic Development Corporation (MEDC), a city agency that deploys a portion of the city’s sales tax revenue as subsidies to companies that are considering locating inside city limits. Two companies that received MEDC subsidies have been the targets of investigations by the federal government, and both have ties to Paxton. One, RMCN Credit Services, agreed to a $2.35 million settlement with the Federal Trade Commission after being charged with using improper tactics in attempting to improve clients’ credit scores. The company’s founder, Doug Parker, has been a legal client of Paxton’s and donated to his campaigns.

Servergy, the company associated with Paxton’s first-degree felony indictments, was approved for subsidies from MEDC as recently as July 2014, even though the SEC had begun investigating the company in August 2013. The SEC alleges that Servergy is, in essence, a fake company that pulled in $26 million by selling stock based on fraudulent purchase orders and a bogus product. In October 2013, the SEC began issuing subpoenas for company emails. Some of the search terms indicate a narrow field of interest, including specific email addresses, Doug Parker’s among them. Other search terms cast a much wider net by, for example, including any and all internal communications with the word “Paxton.”

The indictments issued by the Collin County grand jury allege that Paxton was compensated by Servergy for helping to sell company stock to his unwitting friends and connections in North Texas. One of the men Paxton is charged with luring to Servergy is Cook, his old business partner. Cook claims that Paxton lied to him about his involvement with Servergy, neglecting to tell him that he was being paid to bring in investors. Another Servergy investor, Joel Hochberg, says the same thing happened to him.

The arguments offered by Paxton’s defenders speak volumes about the state’s political culture. His spokesman during these recent travails has been the wily Anthony Holm, who once physically pulled a San Antonio Express-News reporter away from his candidate at a public campaign event rather than have Paxton submit to the indignity of being asked a question. While Paxton has admitted the impropriety of referring his legal clients to Mowery, for instance, Holm argues that the violation is a civil matter, not a criminal one.

That claim and other Holm defenses presuppose that avoiding technical criminality is all that should be required of elected officials. It negates the idea that elected officials — particularly the attorney general — should voluntarily hold themselves, or be held, to higher ethical and moral standards than are codified in law. If it’s the latter standard to which we should hold officeholders, Paxton has already failed spectacularly.

So how has Ken Paxton been able to succeed regardless? While his business entanglements were growing in number and complexity, he was undergoing a parallel personal transformation. An unremarkable politician in many respects — he lacks the charisma and political aptitude of many of his contemporaries — he nonetheless positioned himself fortuitously at the forefront of the rising tea party tide in Texas politics, for which the attorney general’s office was a sort of reward.

The funny thing, Laura Kayata says as she sits on a bench in the hallway of the Collin County Courthouse, is that Paxton used to be a pretty good representative. The grand jury is meeting downstairs, and Kayata is here because it feels like the end of a chapter for McKinney.

Kayata is the founder of McKinney Watchdog, a nonpartisan political action committee and news organization that tries to keep an eye on the city government. McKinney Watchdog is primarily interested in local officials, but over time developed an interest in Paxton, too. Kayata first dealt with Paxton in 2005, when she worked for the town’s chamber of commerce. Former McKinney police officer Aaron Smith came to work with the group after leaving the force over the WatchGuard camera controversy.

Paxton was friendly and well liked, Kayata says, a “small-town boy made good.” People in McKinney thought he had political promise. He helped McKinney make small and unglamorous changes in the law, the bread-and-butter work of a state representative. The chamber of commerce wanted to broaden the ways McKinney could use revenue from the hotel occupancy tax. “We wrote up some talking points for him,” she says, “and then, there he was, reading our talking points on the floor.”

building in McKinney.

BOTTOM: WatchGuard’s police dashboard camera. Google/Watchguard

As attorney general, Paxton has gained national notoriety for grandstanding on immigration, gay marriage and abortion. He presents himself as a fierce and unrepentant champion of the Christian right, and has seemed intent on following Greg Abbott’s culture-warrior path to even higher office. But he began his political career as something of a moderate. In his first campaigns, he urged increased state spending on public education to alleviate local property tax burdens, and he advocated expansion of the area’s light-rail network farther into the North Dallas suburbs.

Before the 2004 general election, the Dallas Morning News issued a breathless endorsement of Paxton, so “impressed by his determination” it deemed him a model for all lawmakers: “We need more consensus builders like Paxton.” The next month, Paxton told the paper his constituents recognized him as a pragmatist. “I think I’ve gotten to know both Republicans and Democrats,” he said. “I think people understand I care about the district. It doesn’t have to do with whether I’m a conservative or whatever.”

But over the next few years, the political culture of the North Dallas suburbs that Paxton represented — and the state at large — changed significantly. Hatred of rising property taxes and government spending came to the fore, and Paxton moved to the right on budget issues, sometimes as a lone conservative voice opposing proposals favored by Governor Rick Perry. Wedge issues such as gay marriage and immigration gained greater political currency. By 2006, Paxton was earning tut-tutting editorials from newspapers around the state for his efforts to repeal the Texas DREAM Act and require benefit recipients to prove citizenship.

That year, Michael Quinn Sullivan founded the right-wing advocacy group Texans for Fiscal Responsibility, which began playing an active role in internal GOP debates. Sullivan soon took a shine to Paxton. In 2007, he won the group’s Texas Taxpayer Hero Award. His positions evolved. When Dallas state Senator John Carona offered a bill to help towns represented by Paxton join the Dallas rail system in 2009, the representative whom the Morning News once lauded for his commitment to transportation issues declared Carona’s bill dead. “Rail doesn’t carry that many people,” he told the paper.

His general election campaign consisted mainly of avoiding public attention. None of the institutions or constituencies that normally hold people accountable in a healthy political system were factors.

It was a turbulent time in the Legislature. Democrats did very well in the 2008 election, but that success would prove short-lived. Despite early press coverage indicating that Paxton might join the 2009 rebellion against then-House Speaker Tom Craddick, he ultimately picked the losing side, voting against the rebel leader, Joe Straus. But it was the right move for Paxton. He’d thrown in early with the anti-Straus coalition, a faction held together in part by Sullivan. In 2010, the year the tea party revolution took effect, Paxton launched a fairly hapless bid against Straus for the speaker’s gavel. Failure again positioned him for later success. For the last six years, the battle between the right and Straus has shaped nearly all aspects of Texas political life, and was responsible in part for the 2014 tea party wave that elevated Paxton to the attorney general’s office.

The tea party had transformed Texas. A comparatively small network of activists — many from the suburbs around the Metroplex — gained an outsize role in the state’s politics. Statewide general elections are uncompetitive in Texas. So the meaningful decisions are often made in the Republican primaries, where a vanishingly small number of people can make the difference. New to power-brokering, distrustful of outsiders, and valuing tribal affiliations above all, many of these tea party activists were perhaps unwilling to ask tough questions of those who sought their support and espoused their positions. Paxton, with the backing of Sullivan and his allies, won an open state Senate seat in 2012, the same year Ted Cruz shocked Texas with his defeat of Lieutenant Governor David Dewhurst in the race for U.S. Senate.

Two years later, Paxton ran for attorney general. The tacit support of Ted Cruz was about all he needed to win. An opposition researcher connected to his right-wing opponent, Barry Smitherman, began shopping a story about Paxton’s violation of state securities law, but when the story was published in the Texas Tribune, it landed with a thud. Texas media — either not read or not trusted by the conservatives whose votes swing primary elections — was essentially irrelevant in the 2014 cycle, and there was no better example than Paxton’s campaign. He wiped the floor with state Representative Dan Branch in his primary runoff, despite the possibility of felony charges.

His general election campaign consisted mainly of avoiding public attention. It was a remarkable way to run for the state’s top legal office, but why should he have done anything else? None of the institutions or constituencies that normally hold people accountable in a healthy political system — the media, the opposition party, an interested public — were factors.

His inauguration was attended by a who’s who of Republican VIPs. Perry, Abbott, Cruz, Dewhurst, Patrick and Texas Supreme Court Justice Don Willett came to speak to an audience packed with notables. Sullivan stood against a wall on the House floor, beaming. In his benediction, Patrick told the audience that he knew Paxton would be “first and foremost a servant to his lord and savior, Jesus Christ.” Paxton stood at the dais with a goofy smile, drinking in the applause and praise. His wife sang the national anthem.

Weston Hicks, a blogger with AgendaWise, which serves as part of Sullivan’s messaging machine, wrote just after Election Day that Paxton’s “honest outsider leadership” and triumph over the haters and doubters should be remembered by all. The subtext seemed to be this: Stand fast as our kind of conservative, and you can get away with nearly anything. So important was Paxton’s victory, the site opined, that Paxton offered “hope for all Western governments.” He had joined the pantheon of the great defenders of Western Civilization, and his name would be written in the stars: Charlemagne, Churchill, Paxton.

Whether or not Paxton is ultimately convicted, he has already shown judgment so poor as to render him unfit for public office. Indeed, a political system with a healthy immune system might have rejected him as far back as 2008, when his casual attitude toward conflicts of interest in the WatchGuard case raised what should have been red flags.

We may be rid of Paxton soon, but what will prevent the next Paxton from winning high office? Genuinely competitive general elections, or at least genuinely competitive Republican primary elections, might help. An overhaul of the way Texas legislators do business might also be prophylactic. In some states, lawmakers are paid a decent wage and are strictly regulated in the kinds of non-legislative business they can take part in. None of the above seems likely in Texas’ short- to medium-term future. A weak ethics bill called for by Abbott died a humiliating death in the closing days of the 84th Legislature.

Neither Democrats nor moderate Republicans have a clear path to power in the coming years. That leaves the state in the hands of the tea party, more or less. Could Paxton be a lesson for the activists who helped crown him? Is the tea party in Texas a matter of mere tribalism, or is it endowed with a real commitment to its members’ avowed principles of anti-establishment, hose-the-decks politics that can be harnessed for the public good?

Kayata isn’t especially hopeful that the Paxton case will change things for the better. “I’m from Washington, D.C. We had Marion Barry as our mayor,” she says with a laugh. “Like, how did that happen? The guy did hard time in a federal penitentiary, got out and got elected.” Closer to home, former Texas Attorney General Jim Mattox, a populist Democrat, was indicted during his first year in office, beat the charges, then served two full terms. Criminality, proven or merely suggested, isn’t always anathema to voters. Paxton’s supporters feel deeply persecuted by the existing political order, and many of them see his travails as part of that persecution.

Paxton’s rapid ascent has been an object lesson in the dysfunctions of contemporary Texas politics. Voters had every opportunity to see him for what he is, and still he succeeded. How?

If Paxton resigns, Abbott’s appointee may well hail from a different tribe of conservatives than the one the tea party favors. So the groups that helped elevate Paxton to the attorney general’s office — particularly those associated with Sullivan — are working hard to keep him there. The charges against Paxton, they say, are just like those against Perry: politically motivated and easily dismissed.

Some Sullivan allies have even suggested that Byron Cook, who happens to be an enemy of the tea party and an ally of House leadership, is, in effect, perjuring himself in order to destroy Paxton. That fits with the Texas tea party’s official cosmology, in which all things are part of the battle between the forces of good and the forces of House Speaker Joe Straus.

Julie McCarty, leader of the Northeast Tarrant Tea Party, wrote on Facebook that Paxton can now “add his name to the list of innocents attacked through the courts by slimy scumballs who manipulate the system at any cost to keep good men down.” If Paxton intends to fight to stay in office, he’ll have to depend on loyal true believers to pressure influential GOPers such as Abbott, who might otherwise be tempted to abandon him.

There is at least a glimmer of hope, though, that even Paxton’s staunchest defenders may be coming around to the idea that the man they’ve been standing by might be less than perfect after all. Back at Cottonwood Creek Baptist Church, McKinney Tea Party member Fred Gonzales said his wife had been a grassroots Paxton supporter from the beginning of his career, and though he, too, thinks the case is baseless, he wishes Paxton had been smarter about things.

“I would have hoped that Ken, knowing the political atmosphere that we have in Texas today, would have been aware of the need, if he made an error in judgment, to have had that situation resolved prior to his election,” Gonzales said.

And on Facebook, after the indictments became public, Mike Openshaw, a prominent figure with the North Texas Tea Party, called Paxton a “friend,” but urged him to “step aside” from his day-to-day responsibilities and put the Office of the Attorney General in the hands of his deputies while the case is ongoing.

The deputies already handle the hardest work. Paxton provides direction and delivers red meat to the Republican base. But in this, too, he is handicapped by his legal difficulties. The day after the McKinney Tea Party met at Cottonwood Creek and word of the grand jury’s existence was leaked to a local news station, Paxton was appearing before a meeting of the Senate Health and Human Services Committee in Austin. The hearing was convened on short notice to discuss fallout from the secretly taped videos of Planned Parenthood staff discussing fetal tissue donation that were released in mid-July.

In response to the videos, Paxton had launched what he described as a civil and criminal investigation into Planned Parenthood’s activities in Texas. He was at the meeting to provide a patina of seriousness to the hearing, convened largely so that senators could express their hatred of abortion. But he seemed distracted and unprepared. He cracked jokes and restated his principles: “The true abomination in all of this is the institution of abortion,” he mumbled. But he was unable to answer basic questions about his investigation. When Senator Donna Campbell, a physician, asked about the techniques Planned Parenthood employs to perform abortions, Paxton asked for her help going forward. “We need doctors helping us think through some of these issues,” he said.

Later that day, the Republican Party of Texas issued a press release about Planned Parenthood. The mere allegation that the group had engaged in unethical behavior should be enough to banish the organization from political life until Paxton’s investigation is complete, it claimed. “They should immediately cease from all political activities in Texas,” said party chairman Tom Mechler. Never mind presumption of innocence; political actors should be held to a higher standard.

On the day Paxton was booked, and his smirking mugshot released, the GOP was more circumspect, releasing a statement saying he should be judged not “in a court of public opinion,” but “by a court of law.”

Paxton will have his day in court. But his credibility as the state’s top law enforcer is already damaged beyond rehabilitation.