End of an Error

East of Brownsville, an unassuming patch of ground hosted the final, pointless battle of the Civil War.

A version of this story ran in the April 2015 issue.

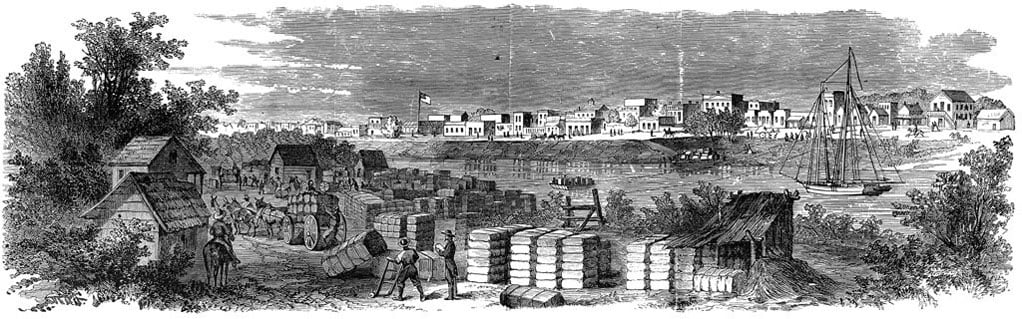

Above: Brownsville occupied by the Union army under General Nathaniel Prentice Banks, November 1863.

War is full of ironies, not the least of which is that infantrymen are asked to spill blood for the sake of occupying a piece of earth that wouldn’t be worth a glance on any other day.

“We go to gain a little patch of ground that hath in it no profit but the name,” complains a captain marching off to war in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. “To pay five ducats, five, I would not farm it.”

So it was with an unremarkable patch of salt prairie to the east of Brownsville, where on May 12 and 13, 1865, a Union advance was beaten back by Confederate artillery fire. About 800 troops were involved at what came to be called the Battle of Palmito Ranch.

Fights for otherwise useless ground were common during the American Civil War, but the Battle of Palmito Ranch stands out for several reasons. For one, it took place 34 days after Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia and 29 days after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination—in other words, about a month after the war had effectively ended.

Furthermore, the clash on the open coastal plain was a decisive rout for the Confederates. The last gasp of the rebellion was a victorious scream.

May will mark the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War at Palmito Ranch, near Brownsville, a battle derided by historian Bruce Catton as a “final, lonely, meaningless little spatter.”

Perhaps the greatest irony of Palmito Ranch was that the final land battle of the Civil War was fought in Texas, a teenage state whose relationship with the Confederate States of America was never especially strong, and whose role in the four-year conflict was mainly logistical.

May will mark the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War at Palmito Ranch, a battle derided by the eminent historian Bruce Catton as a “final, lonely, meaningless little spatter.” The sesquicentennial will likely pass unnoticed by all but the most diligent of Civil War fanboys.

Curious about the largely forgotten spot east of Brownsville and its status as an unlikely footnote in American history, I went to visit the property one day in the company of Wilson Bourgeois, an easygoing IT technician and ex-Navy man who also happens to be the chair of the Cameron County Historical Commission.

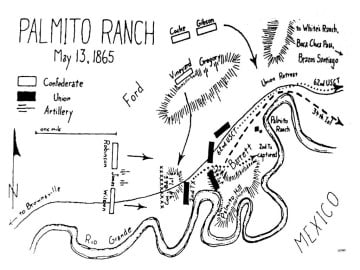

Bourgeois pointed to some trees that concealed the north bank of the Rio Grande. “Those small rises over there? That’s where you had the first skirmishing,” he said, then turned toward open field to the east. “Now that,” he continued, “was where the Confederates were coming on the road from Brownsville. As you see, there’s no cover. The Union had to stay hiding in the chaparral. Then the Confederate artillery came out and rained hell on the Union.”

A modern observer can, in fact, easily see how the rebels won this final engagement of the war. The battlefield has remained practically untouched since 1865, because its value as farmland—or anything else—is virtually nil. It sits today square in the middle of the South Texas Refuge Complex managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and is further protected under the National Register of Historic Places. Texas can therefore boast not just the scene of the war’s conclusion, but an unusually well-preserved battlefield unobscured by marble obelisks or Waffle Houses.

Bourgeois is a methodical historian who wrote a master’s thesis on Palmito Ranch and once walked every inch of the battlefield with his legs tied together with a 2-foot cord so as to maintain the exact stride of a 19th-century infantryman. He is also waging a campaign to celebrate the upcoming sesquicentennial with the huzzah it deserves. A symposium and a battlefield ceremony have been planned. But the governor’s office declined a gubernatorial appearance and the Fish and Wildlife Service said no to a uniformed reenactment—too much possibility of introducing invasive plant species via horse dung, according to the agency. So the reenactment will take place on an ersatz battlefield behind a former shopping mall called Amigoland on the other side of Brownsville.

Perhaps the small-scale remembrance is appropriate, because the slaughter was wholly unnecessary to begin with, and was almost certainly hatched as a vanity project by a hotheaded Union colonel eager for some 11th-hour valor and undiscriminating about where to pick a fight.

A 30-year-old Minnesotan named Theodore Barrett had been given command of the 62nd Regiment of U.S. Colored Troops—composed of free blacks and former slaves—and ordered to stand guard, along with a regiment of Indiana soldiers, on Brazos Island at the mouth of the Rio Grande. There wasn’t much to do on Brazos Island in the spring of 1865 except count the days and swat mosquitos. The war’s end was a certainty. An unwritten truce along the Texas coast had already been brokered by Union Gen. Lew Wallace.

On May 11, Barrett ordered a detachment to the mainland to “round up cattle.” For reasons unexplained to this day, those troops began marching toward Brownsville, where they encountered a line of Confederate cavalry. Shooting started early on the morning of May 12, and Union soldiers advanced slowly through the gunfire to a ranch, where they burned buildings and made camp.

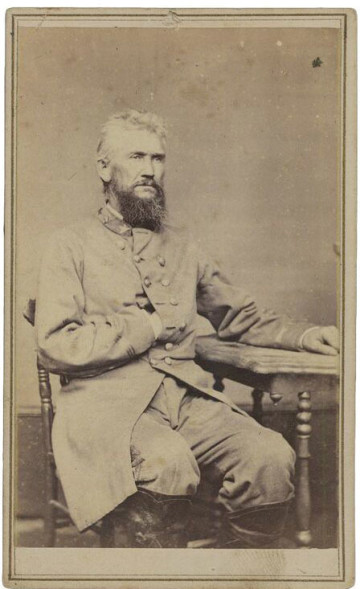

Word of the skirmish reached the rebel commander in Brownsville, a leathery former Indian fighter named John Salmon Ford, who as a Texas Ranger had earned the nickname “Rip” for signing so many death notices with the initials R.I.P. He was also a frontier newspaper editor who loved a good brawl. That night at dinner, his commanding officer, James Edwin Slaughter, told him he saw no point to resisting the Union advance, preferring a retreat into the interior to prevent useless bloodshed. Copies of the New Orleans newspaper, The Picayune, containing news of Lee’s surrender had made their way to Brownsville, though no official orders had yet materialized.

“You can retreat and go to hell if you wish,” Ford told Slaughter, according to books by historians Jeffrey Hunt and Phillip Thomas Tucker. “These are my men and I am going to fight. I have held this place against heavy odds. If you lose it without a fight the people of the Confederacy will hold you accountable for a base neglect of duty.”

“You can retreat and go to hell if you wish,” Ford told Slaughter. “These are my men and I am going to fight.”

Brownsville, however, offered easy access to the wide-open Mexican city of Bagdad, a grimy port that had sprung up to meet the smuggling demand. The federal navy could not touch it. Local profiteers, including Richard King and Mifflin Kenedy of King Ranch fame, got rich shipping mile-long wagon trains full of cotton to Brownsville and exchanging it for gunpowder and medicines to sell to the Confederate army. Within a few years, the price of cotton soared from 16 cents to more than $1.25 a pound. But as Hunt has pointed out, the cross-border trade was always hampered by bandit attacks and high Mexican tariffs; it was not nearly the lifeline the Confederacy had hoped it would be.

Neither was Brownsville a hotbed of secessionist fervor. No cotton was grown in the Rio Grande Valley back then, and there were just seven known slaves in the entirety of Cameron County. When the U.S. Army seized control of the Mississippi River in July 1863, splitting the Confederacy in two, Texas was effectively closed off to the rest of the sputtering rebel economy. Brownsville was therefore only a symbolic prize. But Barrett had broken Wallace’s gentlemen’s agreement not to march on the town, and he would pay.

Despite the illogic of the pride in play, Ford was likely having the time of his life on the morning of May 13, when he sent men out to halt the Union advance. It wasn’t the first time he had seen an incursion along this road—his forces had beaten back an earlier federal attempt on July 30, 1864. This time, he was aided by the incompetence of his adversary, Col. Barrett, who had unified his columns and was advancing at dawn into Confederate rifle fire. The march was hot, slow and dangerous.

“It was all walk and fight, walk and fight,” said Bourgeois. “It was an all-land movement, which was their mistake. As you can see, there’s no place to hide. They had to lie flat in the chaparral.”

The closer Barrett’s line drew to Brownsville, the more he cut himself off from his supply base. Morale among his 500-man force was waning. At around 3 p.m., when “Rip” Ford arrived on the field with 12-pound artillery guns on caissons trundling behind him, the Confederates got a new burst of energy. “Men,” Ford yelled, “we have whipped the enemy in previous fights and we can do it again!”

He ordered a flank attack, which struck Barrett’s men from the north—a tactic that had always worked against the Comanche—and dozens of Texans screamed the Rebel Yell for the last time. Coordinated artillery fire and a cavalry charge added to the blanket of confusion surrounding the hapless Union soldiers. “Never before had these Federals, veterans or rookies, been more unready for battle than now,” according to Tucker.

Union soldiers both white and black were driven to the banks of the Rio Grande, where, incredibly, French soldiers then occupying Mexico under the puppet emperor Maximilian I began taking potshots at them from across the river. At least a few French officers were said to be on the north side of the Rio Grande helping the Confederates aim their cannons.

The casualties were never accurately counted, but there were reports of blue-uniformed corpses choking the river. The Union lost up to 30 soldiers that day, compared to none for the grays, and Barrett was immediately held up for blame. One of his men wrote to a Nashville newspaper that the young colonel had ordered the foolish attack “to establish for himself some notoriety before the war closed.” Palmito Ranch’s second day of fighting coincided with the day that Texas’ governor agreed to the surrender of his state, and Brownsville was quietly passed to the control of the U.S. Army just three days after the last shots were fired.

Barrett tried to shift attention from himself by calling a court-martial against a junior officer. Before disappearing to Indiana and a failed political career, he left some gracious words of praise for his African American troops, who had refused to panic under heavy fire. Ford retired to a quiet life as a newspaper editor. “There were reasons on both sides that made it preferable to forget” the battle, “and so it was,” concluded historian T.R. Fehrenbach. The Union was embarrassed about the ingloriousness of the pointless carnage, and while the Confederates drew some pride in giving the Yankee interlopers one last licking, it happened in the twilight hours of their dying national dream.

That the Confederacy should have flickered out in Texas was, in its own way, a testament to how far the state was from the Confederacy’s primary theaters. Other than its supporting role as a smuggling base for cotton and a supplier of horses for cavalry, the state was mainly an object of future hopes. Jefferson Davis wanted to use it for a railroad to the Pacific and an extension of slavery into California. Texas produced only one native-born general—Felix Robertson—and never wielded much influence in the Confederate capital of Richmond, though it is worth noting that the only Confederate cabinet member who did not desert Davis was Postmaster General John Reagan, a Texan who fled the capital at the president’s side in front of advancing Union troops and was captured with Davis in a grove of trees near Irwinville, Georgia, on May 10, just days before the shooting started at Palmito Ranch.

The casualties were never accurately counted, but there were reports of blue-uniformed corpses choking the river.

The state’s comparatively light experience with battle on its own soil meant that Texas was spared the worst psychological blows of defeat.

Texas would soon be concerned with other matters. With a proud tradition of independence behind it and oil, technology, urbanization and space exploration yet to come, the state never really got caught up in the Lost Cause narrative that still haunts the collective memory of the other separatist Southern states. Had the Battle of Palmito Ranch been fought in Alabama or Mississippi, the place would likely have been turned into a shrine littered with monuments and gift stores. Instead, it lives on mostly in the memoir of Jefferson Davis, who wrote, “Though very small in comparison to its great battles, it deserves notice as having closed the long struggle—as it opened—with a Confederate victory.”

In Texas, meanwhile, the site of the struggle’s close remains nearly forgotten, accessible by a secondary road near the Brownsville Ship Channel and marked with a roadside plaque.

For Bourgeois, the legacy of Palmito Ranch is broader than its significance as an asterisk:

“This was the end of a really terrible time,” he told me. “This was the end of disunion.”