Fight for Wright

In a town haunted by its racist past, a mysterious death prompts a search for justice.

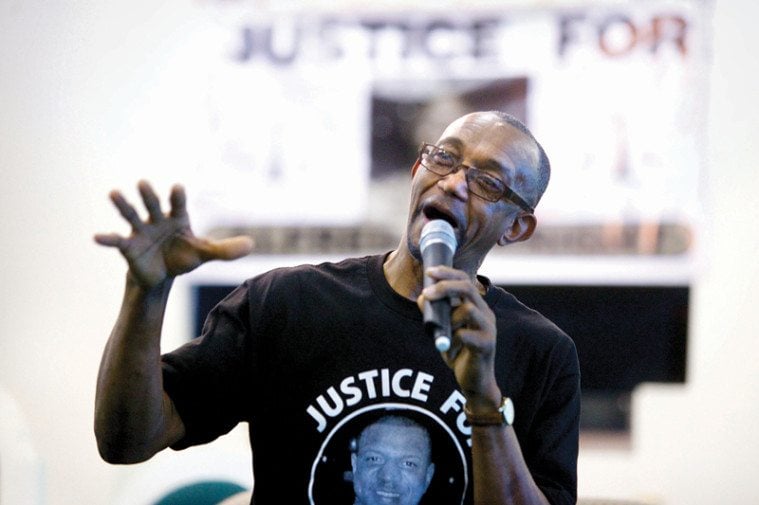

Above: An armed "Justice for Alfred" protest through downtown Hemphill in February, with New Black Panthers marching alongside members of Alfred Wright's family.

On a rainy day in late November, shortly before Thanksgiving, a group of volunteers gathered near a thickly wooded stretch of State Highway 87, just south of the deep-East Texas town of Hemphill. A private investigator named Chuck Foreman, an Army special-ops veteran with a rugged, road-ready biker look, divided them into groups of four and handed a walkie-talkie to each team leader. On a U.S. Forest Service map, he assigned each team a route, pointing out the ponds and streams they’d encounter along the way, and the two-track hunting road where they’d regroup. A little after noon, bundled up against the stiff northeasterly wind, they fanned out into the woods in search of Alfred Wright.

These were the same woods volunteers had combed a decade earlier, after the Space Shuttle Columbia broke up in the sky over Texas—a museum in Hemphill memorializes the tragedy. A fruitless search for Wright, led by the Sabine County Sheriff’s Office, had penetrated nearby woods just two weeks prior. Dogs, volunteer firefighters, local cops, federal agents and even the mayor of nearby Jasper flying his own airplane scoured the woods for days.

Wright was a 28-year-old physical therapist from Jasper, about 45 minutes away, on his way between jobs when he pulled his overheated truck into a liquor store parking lot outside Hemphill. He stayed outside, passed small talk with a sheriff’s deputy who’d gone in for some beer, and called his wife for a ride. When Wright hung up, the store’s clerk saw him sprint up the highway toward Hemphill. He called his wife one more time, breathing heavily and sounding worried before hanging up. An hour later, his parents came to pick him up, but he was gone. Officials found Wright’s clothes scattered around a field and tangled on a barbed-wire fence, but the dogs lost his scent at a nearby creek. Wright went missing on a Thursday, and by Monday the search was called off. Wright’s family and friends, along with a growing number of local residents, said the search wouldn’t have been abandoned so soon if the missing man weren’t black, but Sheriff Tom Maddox promised his investigation would continue after the ground search ended. Weeks later, the sheriff had said little about the case.

Wright’s family found other signs that local officials weren’t taking the case seriously. Volunteers from Jasper had been turned away from the official search, told they were too late or weren’t in good enough shape or were wearing the wrong clothes. Over that first weekend, a Hemphill cop joked on Facebook that Alfred was probably just laying low, enjoying a beer on the beach somewhere. Sheriff Maddox remarked that he was missing out on good hunting to lead the search, then outlined an elaborate scenario in which Alfred was out on a bender and wouldn’t resurface for a week or two. Despite the strange circumstances, and the trail of clothes and belongings around the pasture, Maddox said nothing suggested foul play, just “red flags.” Alfred’s truck still hadn’t been searched, nor had any family members been asked for sworn statements.

So on the 18th day after the disappearance, Alfred’s family and friends from Jasper took up the job, combing private land adjacent to the site of the official search, which the owner said had never been inspected. It was a popular hunting spot at the start of deer season, but the volunteers braved it. Tearing through briars, sliding down hillsides and splashing into muddy creeks, they pushed across the terrain. Three hours in, a strong wind blew past one of the team leaders, an ex-Marine from Jasper named Yahtorah Kupenda, and with it came an unmistakable scent. “You could smell death in the woods,” he said later.

Kupenda followed the smell to a wall of thick bushes and thorns and pushing through, he emerged into a small clearing. In a ditch to his right, he found a man’s body, face down and stripped to his underwear, shoes and one sock. The skin was ashy gray with patches of white, the neck discolored, dark like a bruise. The left ear was gone. Kupenda yelled into his walkie-talkie: “I found a body here!”

The small clearing was surrounded by bushes and young trees, with just one path out, leading to the pasture officials had searched weeks earlier. Rev. Douglas Wright Sr., the missing man’s father, rushed in to see the body. Wright recognized the angel wings tattooed across his son’s shoulders. “They killed my boy,” he said, “they killed my boy.” By then it wasn’t even a surprise.

Douglas Wright was the fourth of 14 children raised on a farm outside Hickory, Mississippi. The family home was little more than a big shack, with a leaky roof and holes in the floor. He could watch the chickens walking underneath. But the household was a nearly self-sustaining operation, raising farm animals and growing hay, cucumbers, peppers and cotton. With his siblings, Wright sold the crops at the market in town and delivered milk around the county.

At night the kids gathered around the TV and watched the civil rights movement unfold on the news. Before Wright entered eighth grade, Mississippi’s schools began racial integration under a “freedom of choice” policy, and he and two older sisters decided they’d be the ones to break the color line at Hickory High School. They waited until a few days after the school year started, then walked in together. “I tell my kids now” he says, “‘Y’all don’t understand.’ The word, the N-word, nigger, was a song for me every day. They sung it to me, they called me nigger so much.” Students spat on him. Teachers explained that the white students were smarter than he was, and for four years, Wright and his sisters were the only black students in school. By the time he graduated, though, some of the kids who’d been the meanest at first had become his friends. After watching white students in class, he realized they weren’t really smarter, despite what he’d been told. “People wonder how I could be strong,” he says today, “and it’s because I know what hope and perseverance bring. It actually brings about change.”

Wright’s father, Clovis, was a pastor who preached for a time at Mount Zion Methodist Church near Philadelphia, Mississippi. In 1964, the church was a gathering place for civil rights activists aligned with the Congress of Racial Equality, one of the nation’s most influential civil rights groups at the time. Sometimes when Wright rode home with his father—a black man and his 10-year-old son on a remote 40-mile stretch—white men in cars would ride their bumper, flashing headlights. Threats like that happened often enough that Wright’s father kept a pistol under his seat. Then he got reassigned to a new church. Only later did his father explain: “Those peckerwoods was picking on me, and either I was gonna hurt one of them or they was gonna hurt me. So I asked to be moved.” Clovis was transferred to another nearby church, and a few months later the Ku Klux Klan set fire to Mount Zion. As a symbol of resistance, the congregation rebuilt the church, and the Klan burned it down again. It was burned and rebuilt three times in the 1960s.

That first church burning touched off a brutal period that became known as the Freedom Summer of 1964, when three civil rights workers were shot and killed while investigating the arson. Two were white men from out of state and one was a black man from nearby Meridian named James Chaney. Officials wouldn’t release the autopsy results, but suggested that all three had simply been shot. Civil rights activists suspected the crime had been even more savage. It took a pathologist in New York, hired by a civil rights group, to perform a second autopsy and confirm that Klansmen had beaten Chaney, shattering his bones, before he died.

“Law enforcement was working with the locals. Even the FBI was working with the locals to try to keep things hush-hush,” Wright says. “And when they did convict them, and it was obvious that they’d done it, they still got life sentences. And it was a fight to get it done. And so I knew the history, this thing has been a revolving door all through the years. I’ve kept up with every race case that has come up through the years. And it’s been a fight, it’s been a fight to get justice in every case.”

The rest of the searchers gathered in the open field. Pastor Ray Lewis, Alfred’s godfather, who had posted “missing” flyers from Hemphill to Jasper, broke down in tears. Someone brought Lewis’ church van back down the dirt road so the volunteers could warm up inside. A few men built a fire. Jasper City Councilman Alton Scott called 911, and they waited for investigators to arrive.

Sheriff’s deputies came less than half an hour later. Three of them walked the path into the clearing and began taking photographs of the body. They said they’d take the body to a funeral home in Hemphill, but Wright refused, insisting on waiting for a Texas Ranger. When Ranger Danny Young arrived from Jasper after nightfall, Wright demanded a different ranger. Young was surprised—the two were hardly strangers, and Wright taught Young’s children in gym class at school. But Wright had learned that Young and Sheriff Maddox had once worked together at the Texas Department of Public Safety, and so deep was his distrust of Sabine County officials that he insisted on someone else. “It’s not about trusting you,” Wright told the ranger. “It’s about me having to live with this for the rest of my life.”

Ranger Steve Rayburn was the next-closest, hours away in Lufkin. He couldn’t arrive until the next morning, so Wright agreed to wait overnight beside his son’s body. Deputies unfolded two tent canopies, one over Alfred’s body, the other to shelter Wright, Kupenda and a new Sabine County Sheriff’s deputy who’d been assigned to the scene overnight.

Wright sat awake all night in a folding chair with his son’s body a few feet away. (He could see the light from the house across the pasture, where weeks earlier the old farmer and his wife fixed dinner for him and his wife, Rosalind. The farmer had offered them a place to sleep inside, but he and Rosalind had spent those nights outside in the car.) With rain splashing the mud and tapping on the canopy, Wright waited out one more night in the field, sustaining himself with a few peanuts he’d stuffed in his jacket pocket. The three men stayed awake talking as the dark hours passed. They spoke about Alfred, a high school football star who was still modest after he returned from college in Memphis, who took his new job as a therapist, traveling to appointments miles from home so he could buy a new truck for his family. And they spoke about Jasper.

The deputy was new to town, but any conversation about Jasper’s reputation has an easy starting point: the 1998 murder of James Byrd Jr., the black man who accepted a ride from three white men—two with ties to a white supremacist prison gang—who drove him to a field, beat him, chained him to their truck and dragged him for more than 3 miles. Along with the 1955 murder of Emmett Till, it’s one of America’s most notorious hate crimes. While the murder led to a period of soul-searching and frank talk about Jasper’s racial dynamics—much of it broadcast for the benefit of the worried world outside—it’s also an incident the town’s white leaders have grown weary of hearing about. The men who killed Byrd were swiftly caught by local authorities and severely punished, after all: one executed, one on death row, the other serving life in prison.

While some in town find the attention unfair, a series of recent incidents suggests that Jasper has lingering racial tensions. In 2011, after a majority-black City Council hired Jasper’s first black police chief, a group of white community leaders—including the mayor—complained the chief had been hired over better-qualified white candidates. They organized a special election to recall three black council members, and succeeded in recalling two, who were promptly replaced by white candidates. The black police chief was fired. In 2013, two white police officers were caught on camera beating a black woman inside the Jasper police station. Once again, many whites dismissed the idea that the beating reflected anything about the town—it was a violent aberration, they said, and the officers responsible were fired.

Wright moved his family to Jasper in 1988 and took over as pastor of Jasper Circuit Memorial United Methodist Church. A few years later, he joined the Jasper school district as a gym coach. Even before Byrd’s murder, he was an outspoken critic of the town’s racial divisions; after a black basketball coach was fired without explanation, Wright joined a student walkout and spoke at a rally. The town still runs, he says, like a Southern plantation; blacks are punished for stepping out of line. He saw the way black students were intimidated, and he worried for Alfred, who was always bold, who was childhood friends with the white girl he’d go on to marry. And now, a few days before his 60th birthday, Wright sat outside on a cold rainy night, facing the prospect that the violence he’d known from his childhood in Mississippi had claimed his son too.

Ranger Rayburn arrived in the morning, along with other law enforcement officials, to document the scene. Wright made a soggy trek to the farmer’s house, where he got a dry pair of socks and warmed up by the fireplace. He regrets those hours now, when he left his son’s body alone with the officers.

They took Alfred’s body to Beaumont, where John Ralston, a pathologist contracted by Sabine County, performed the autopsy. Ranger Young supervised. Wright—remembering Freedom Summer, when the truth about the civil rights workers’ murders came only after a second autopsy—hired a pathologist from Houston to conduct an independent examination.

On Nov. 30, hundreds of friends and family filled the Nehemiah Life Center in Jasper for Alfred’s funeral. Photos of Alfred, his wife Lauren and their sons were projected on the wall. Wright spoke, as did Lewis and a handful of other leaders from Jasper’s black community. They buried Alfred in a dark-blue casket, and while marking the end of Alfred’s life they started something new: a fight for justice—or at least to understand what happened—and to keep Alfred’s memory alive.

The strange details of the case, and Jasper’s reputation, attracted civil rights activists from Houston to the cause, like former New Black Panther leader Quanell X, who met with Sheriff Maddox and marched outside the department. “For some reason it seems like African-Americans are still suffering like it was in the ’60s,” Quanell X explained at the time. “East Texas is the last bastion of great hate that has not been dealt with by the mass of Texans.”

The Bernsen Law Firm in Beaumont—which was handling civil rights suits on behalf of Jasper’s fired black police chief and the woman beaten by Jasper police—took on the Wrights’ cause as well, and hosted a December press conference in Beaumont that kept local media attention on the case. On a map, attorney Ryan MacLeod pointed out where Alfred’s body had been found and just how close it had been to the original search, wondering how so many law enforcement officers could have missed it. Having just visited the site a few days earlier, he set the scene: “I can’t explain it in any other way, but it is a creepy, creepy road. It is a dark road. God bless those who live out there, but I’m not going to. It’s not a place that I would be by myself at night, and it’s not a place that Alfred Wright would be on his own at night either.” Perhaps most disturbingly, he said Alfred’s body had been found in precisely the area his family asked the sheriff to search during that first weekend, but they’d been told it was off-limits to the volunteers. Though local officials had consistently said they found no evidence of foul play in Alfred’s death, the Wright family’s hired pathologist, Lee Ann Grossberg, announced that she had a “high index of suspicion of homicidal violence” after examining Alfred’s body.

Grossberg delivered the message to a row of TV news cameras in a room filled with Jasper residents who’d driven an hour to hear the news firsthand. Some spoke of how heartened they were at the outpouring of support from Jasper; others spoke of how dangerous Hemphill was if you’re black, more so than Jasper. Hemphill too had one brutal event in its recent past that served as shorthand for its violent reputation: the killing of Loyal Garner Jr., a Louisiana man beaten to death in jail by Hemphill’s police chief and two sheriff’s deputies on Christmas Day 1987. Prosecutors had to get the trial moved to Tyler to secure convictions. Today, the Sabine County Sheriff’s Office is housed in a building named for the sheriff at that time, Blan Greer.

After the press conference, a Christmas Eve vigil in Jasper followed, then a march in Beaumont featuring the Wright family and an empty white coffin with a framed photo of Alfred inside. At a 5K run fundraiser—collecting money to support Lauren and her boys—Wright’s family sold lime-green T-shirts with a name for their cause that reflected their nonspecific, abiding frustration: “P.U.S.H.—Push Until Something Happens.” The gatherings became a chance to share other stories as well: intimidation, beatings and disappearances that were discussed in the black community but never considered newsworthy in the white community; cases in which families suspected a police cover-up or lax investigation, but could never prove their doubts, and the cases just quietly went away. Though no one knew what had happened to Alfred, his case drew out the tales of other injustices visited on the black community, the way Byrd’s and Garner’s murders had.

In January, the Texas Department of Public Safety released the official autopsy results, which noted no signs of trauma on Alfred’s body. The autopsy attributed his death to a lethal dose of cocaine and methamphetamine. To those who’d been convinced of a cover-up, the results were no surprise. The report noted Alfred’s missing ear, along with missing eyes, tongue, three teeth and a fingernail—which Ralston attributed to decomposition, wild animals and insects, but which the suspicious saw as signs of torture. Citing their ongoing investigation, state investigators refused to comment further on the case. In the absence of official answers, new theories grew.

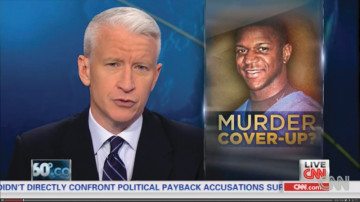

In mid-January, CNN’s Anderson Cooper 360° introduced the Alfred Wright mystery to the world with the words “Cover-Up?” floating over the newsman’s shoulder. In the report, Lauren Wright, strolling across the Sabine County pasture where the first search came up empty, recalled her last phone calls with Alfred. Attorney MacLeod described how unhelpful law enforcement had been, and from outside the sheriff’s department in Hemphill, reporter Deborah Feyerick pleaded unsuccessfully for Maddox to answer her questions. Feyerick recalled the strange trauma to the body, quoted Grossberg’s suspicions and added a dramatic new detail: “It seemed his throat had been slashed.” Though Ralston hadn’t mentioned making the cut in his report, and Grossberg never observed it either, Texas Rangers apparently told Feyerick that the incision was part of the first autopsy. Alongside Anderson Cooper in the studio, the show’s medical expert explained that, based on the animal and insect activity, Alfred’s body had likely been outside for only a matter of days, not weeks. The stories ran over three nights, culminating with a tantalizing theory about a dime Kupenda found in the dirt a few feet from Alfred’s body—Feyerick explained it could be a warning against snitches—and an interview with Maddox’s ex-girlfriend Brenda Chastain, who told a spooky tale of having found dimes in her home and car when she and Maddox were dating.

The CNN story broadcast other suspicions that had existed, to that point, only in local rumor: hotel receipts from Alfred’s stays in a Jasper hotel while his family was out of town, and a possible tryst with Sheriff Maddox’s daughter, who booked home health appointments with Alfred and other therapists. Maddox’s daughter denied it, but locals wondered: Could Alfred have been killed by an older white man enraged that his daughter was dating a black man? Another suspicious figure emerged apart from Maddox: a white former prison guard in Hemphill named Nathan Ener, whose daughter Ashley had worked with Alfred. Ener’s Facebook page was full of photos and news links about Alfred’s case, with comment threads where others mocked the “Justice for Alfred” protests. In another widely shared photo from his page, a group of white men in masks and camouflage sit holding rifles, as if about to go for a hunt.

After the CNN story, the media attention intensified thanks to an odd coincidence. Alfred’s younger brother Savion happened to be a contestant on the Fox show American Idol at the time, and in February he dedicated a song to Alfred on the broadcast, saying only that his brother had recently died. The mention sparked huge new interest in the case from entertainment sites and even Good Morning America. Trumpeting their “EXCLUSIVE” report, London’s Daily Mail repeated the mysterious tale, dressing up the family pathologist’s cautious suspicion with tabloid drama: “An ‘affair’ with white sheriff’s daughter, drugs and claims of a race crime cover-up: Disturbing death of American Idol star’s brother who was found naked, with his tongue missing and throat slit on Texas ranch.” There was still no news from state investigators, nor solid leads from local tipsters, so news and entertainment sites rearranged familiar suspicions into macabre fables under headlines like, “Cops Blame Drug Overdose For Death Of Black Father Found With Throat Slit & An Ear Missing,” and “The lynching of Alfred Wright in Texas proves Black History Month is still imperative.” Beyond the click-bait hyperbole, though, the stories reflected something Alfred’s family and friends in Jasper were grappling with too: the need to find meaning in his confounding death.

Fifteen years ago, in the months when James Byrd’s killers stood trial one after another, Ray Lewis was building a new church. Standing beside one of Jasper’s public-housing projects, Lewis’ Faith Temple Church of God in Christ is a plain metal-sided building with plush green carpeting, a balcony inside, and seating for several hundred. In 2011, when Lewis led a counter-recall effort to remove Jasper’s white mayor, someone broke a window and ransacked his office. On a Saturday morning in February, the church hosted a peace rally for Alfred Wright.

Supporters streamed into the pews, and New Black Panther Party members stood outside, distributing flyers calling Wright’s death a murder and a cover-up. Jasper’s new police chief, Bob McDonald, helped direct traffic. “Rebranding the department” was one of his biggest jobs now, McDonald told me, so he was there to meet people, and a few hours later Jasper police would escort a caravan of cars from the church to a demonstration in Hemphill. In his first few months on the job, McDonald bought cameras for officers to wear on duty and ordered stickers for the police cruisers that read, “Unity in our Community.”

“You know, my heart goes out to the Wright family, because they’re looking for answers and they’re getting pulled in all different directions,” McDonald told me. “The family is going to get justice. It’s going to happen. It’s just going to take time.”

Douglas Wright began the rally inside by reciting the strange circumstances of his son’s death, describing how superficial the investigation seemed and how it was singularly focused on establishing Alfred’s death as a simple drug overdose. He said Sabine County officials had been guarded with the evidence they found—like Alfred’s clothes, which the family had never been allowed to see—and indifferent to any information the family offered. No one in the Wright family, nor any of the volunteers who found Alfred’s body, had been asked for sworn statements. Even if it were an overdose, he said, there were still so many mysteries, like why Alfred’s legs weren’t scratched when all the volunteers’ clothes had been torn up during their search. Or the perfectly rectangular piece of Alfred’s medical scrubs police found hanging on a barbed wire fence. “I’m a country boy from Mississippi,” Wright said, “have about 10 scars on my legs from jumping barbed wire fences. Never in all of my jumping and tearing pants did I ever tear a rectangular piece off and leave it hanging on a fence. My son always did a lot better than me, I guess.”

The media attention on the case had attracted an improbable lineup of do-gooders to headline the rally, and they took turns discussing the case. These included the private investigator Chuck Foreman, a Fort Worth lawyer who represented the comedian Steve Harvey in his divorce, a self-described “celebrity realtor” from New York, a Houston radio host who’d been following Wright’s case, and a motivational speaker named Johnny Wimbrey.

Wimbrey had made his first trip to Jasper weeks earlier in a friend’s private plane, arriving at a 5K run fundraiser in a black stretch limo and promising that someone was on the way from Dallas with his books—all the money from sales, he said, would go to Wright’s family. He promised his international connections could raise even more money for the cause, and his fans would help keep pressure on local officials. Some of Wimbrey’s followers came from a travel club called WorldVentures, a direct-selling business that’s been criticized as a pyramid scheme because members get big rewards for enrolling new members. One woman wore her WorldVentures shirt to the rally at Lewis’ church. She carried flyers and began conversations with, “You look like a traveler…” Still, Wimbrey had already donated thousands to the Wrights’ cause, helped raise thousands more, and paid to fly in many of the guests.

Strolling around the church with a microphone, Wimbrey was a font of good vibes, expounding for the people of Jasper on the power of positive thinking. And he played on Wright’s last name to make his points. To him, the case wasn’t about race, he said, but about what’s right—“W-R-I-G-H-T.” He led the crowd in a callback chant:

“We’re here to get justice for who?” he prompted.

“Wright!”

“By doing what’s…”

“Right!”

Audience members stood and asked the panelists about theories they’d heard, possible avenues for investigation, or suspicious characters in Hemphill. One man from Sabine County said he’d known, as soon as he heard Alfred was missing, that the cops had done something terrible. The panelists proclaimed their commitment to the cause, and though some had tenuous connections to the case, their messages sounded genuine. “We can’t be cowards with spineless vision,” said the Houston radio host Jeffrey Boney. “We have to be heroes to our children and our next generation. Forget those that don’t want to get on the train. You need to step up and you need to say something to reach out to your black press and let them know what’s going on in your communities.”

“This is the great beginning of unity for all of you,” said the Fort Worth lawyer, Bobbie Edmonds. “For all you young people, I want you to learn from this process because you see that the adults are seeking justice. And in reality, justice is not always in the place where you think it should be.”

Savion Wright, who’d been eliminated from American Idol just days earlier, played a keyboard and guitar, and sang alongside two other former Idol contestants. His sister Annilia made a special request—“A Jasper favorite,” she said—for Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come,” and he played as the church audience cheered him on. Annilia called the rest of her family to stand before the crowd and handed out award plaques to the panelists, the Idol contestants, and other supporters like Ray Lewis. Annilia summoned Alfred’s ex-girlfriend and his oldest son to stand with them onstage to demonstrate the family’s unity. And to show that they were looking out for Lauren, Annilia announced there was a new car waiting outside for her, the one Alfred never had the chance to buy his family.

It left the feel-good impression of a telethon, but one moment rose above the rest: when James Byrd’s sister, Betty Byrd Boatner, rose from a pew, took the microphone and offered a passionate prayer before the congregation. “When I heard, Pastor Wright, I got down on my knees and said, ‘Lord have mercy for the family,’” she said. “‘Lord have mercy on this family, because I know how you feel.’” She spoke faster and louder, her voice muffled in the church sound system, and then knelt at the feet of Douglas, Rosalind and Lauren Wright, shouting, “Glory be to God!” and hugging them as they all sobbed.

It was a startling moment, the outpouring of raw emotion from two families now well practiced at public grief. Savion at the piano laid down a stirring soundtrack as Boatner stood and handed over the microphone. Annilia proclaimed to the crowd: “That is what love does!”

Hear Savion Wright play Sam Cooke’s “A Change is Gonna Come” at the rally in Jasper

At that moment about an hour away, there was distinctly less love in Hemphill’s town square, where members of the New Black Panther Party milled around. Some carried rifles, shotguns and flags, and greeted motorists with black-power salutes from the courthouse lawn. Krystal Muhammad, chair of the New Black Panthers’ Houston chapter, paced the street with a megaphone, explaining that hers would not be a peace rally: “You thought we were gonna sing a damn song, didn’t you? Thought we were gonna tap-dance and play basketball. Fuck that, you no-good racists. You no-good racist devils, you’ve killed a lot of people. You’ve spilled their blood in these streets.”

Gathered under storefront awnings and behind parked trucks, resting on the tailgates, a nearly all-white crowd of locals watched the strange scene unfolding. Some of them had been part of the original search crew, devoting their weekend to finding a man they’d never met. Kyle Newton, a young man from nearby Newton, told me he even shared suspicions about the case—why, after two weeks, the body hadn’t been devoured by scavengers, or how search dogs could have missed the body, close as it was to the search’s starting point. But he didn’t see what any of this protest had to do with Wright’s case. “They’ve been trying to get a riot started. They’ve been calling for the KKK to come out,” he told me, “threatened to burn this whole place down.”

Newton went on. “They always want to throw race into it and bring up slavery and all that shit. In all actuality, I don’t know if you’ve studied about slavery, but their own people’s the ones sold ’em into it. … I’m sure there were some that were treated bad, but the majority of them, they were treated very, very well. I mean, you have a tractor, and it’s the way you make your living, you’re gonna treat it well,” he said. “And they’re saying that all of us are guilty of it just ’cause we’re white. They don’t know if it’s a white man or a black man that did it. They’re trying to piss people off is what it is.”

Among the locals gathered to watch what quickly became the strangest Saturday afternoon in Hemphill in memory was a man in boots, brown hunting camo and a tall cowboy hat, towering over the crowd and chain-smoking cigarettes to calm his nerves. Nathan Ener, like many others looking on, had grown up in Hemphill and took offense at the accusations being leveled. Unlike the rest, as he saw it, he was prepared to do something about it.

Ener had worked in the oil business before he became a prison guard. In the late ’90s, he endured a string of prison riots at the Terrell Unit—“Mexican against the whites,” he says—that broke his spine and both legs. He got metal knee implants and metal supports in his legs and defied the odds by walking again. But the injuries forced him to retire from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice in 2001. He moved back to Hemphill.

He got wrapped up in the Alfred Wright case by accident, he says, after Foreman questioned his daughter Ashley about her friendship with Alfred. Ener suggested Foreman come to him if he wanted answers. Along with Sheriff Maddox, Ener quickly became the face of whatever dark secrets Hemphill hid. But Ener says the outsiders trying to paint Hemphill as some backwoods Klan haven are off-base—it’s a small town where folks get along. He can think of a handful of racists in town, and they aren’t white, he says. Ener was a third-grader when Hemphill’s schools integrated, and one of his best friends then was a black boy he nicknamed “Puppy,” because of his chubby cheeks. “He named me Sasquatch,” Ener says. Ener stuck up for him in fights, and he says they’re still friends today.

Though he’s argued with Maddox in the past, he says the sheriff has been treated unfairly. The search for Alfred went on far longer than the first weekend, for instance—days later, he saw a swarm of police cars parked on the road to search the area. A week after that, he heard DPS helicopters searching overhead. “That man’s got nearly 50 years of law enforcement experience,” Ener says of Maddox. “If that was a bad man, don’t you think in 50 years he would’ve showed it?”

But now here was Krystal Muhammad shouting at the county medical building, where a small army of cops and state troopers waited behind the doors, daring Maddox to face her in the street: “It’s a goddamn murder, and you’re part of a conspiracy to commit murder!”

Quanell X strolled the streets in a suit. Ener recognized him from TV, when he was on Bill O’Reilly’s show calling for white people to be killed. Quanell X recognized Ener from his Facebook posts.

“I know why you’re upset. You’re upset because of Ashley,” Quanell X taunted Ener as they met in the street. “’Cause your daughter likes black coffee, no sugar no cream. That’s why you’re upset. It’s eating you up, ain’t it? That she likes a black man?”

Ener called to a white man on the sidewalk.

“Ben, does any of my people—any of my family like black folks?”

“Not that I know of.”

Quanell X goaded Ener: “Ashley does! Ashley does! Now let me tell you something, peckerwood. I will whup your ass. I’m that one.” He peeled off his suit jacket, stepped up inches from Ener’s face, and the two jawed to the crowd’s amusement. A line of uniformed troopers filed out of the county building and led Ener away.

Ener was told to wait behind the county building, and once he’d cooled off, another officer gave him a choice: Go back home, or go to jail. He’d only been inside his house for a few minutes when a dozen trucks pulled into his driveway with men asking him to organize a counter-protest the next weekend, because there were some groups anxious to help defend the town. Ener posted on Facebook a photo of himself in his kitchen, staring down the camera with one hand in his pocket and the other on the grip of a rifle. The caption reads, “I have one too!!” Then he announced a rally the next Saturday, encouraging locals to bring their families and their guns. “There won’t be any foul language used, there won’t be any threats made to anyone, we are not going to stoop down to the level of those Panthers,” he wrote. “There will be seven or eight groups, a few of the groups will be Redneck Mafia, Sacred Bones Society, Pineknot Mafia, White Nights of the Ku Klux Klan and a couple bike clubs.” He canceled it soon after, thinking better of starting something he couldn’t control. After James Byrd’s murder, while he was working as a prison guard, Ener had helped with security when the Panthers and the Klan faced off in Jasper. “All they said was the N-word and ‘I hate blacks,’” he says, “and I’m not like that.” His problem, he decided, was a personal feud with Quanell X. Sorry as he was for Wright’s family, it was hard to see how the Panthers’ protest helped.

After Ener left the square, the caravan arrived from Jasper. Panther leaders and Wright’s family marched a short distance around the block, returning to the courthouse steps where Anillia Wright presented Quanell X with another of the awards handed out at the peace rally. Douglas Wright took the megaphone and turned to the county building filled with deputies and state troopers. “He didn’t take the drugs, you put it in his system!” Wright yelled. “You know where you laid him at.” Wright recalled the Freedom Summer of 1964 and the fights for justice in his childhood. “We’re just letting you know that what our forebears took, we won’t take no more. What you got away with then, you will not get away with now.

“My son was only a sacrifice, and his sacrifices will not be in vain. He will live because he lives through my brothers and sisters that are here. … We will avenge his name. We shall love. We will show care and concern. We will not give up because we’ve come too far.” And then, along with his message of love, Wright leveled a warning: The fight for justice, he said, would come by any means necessary. “I don’t like Sabine County, and I don’t like Hemphill either. But I ain’t going nowhere. You’re gonna think I love you!”

Mystery still surrounds the death of Alfred Wright. Sheriff Maddox declined to comment for this story or to address the criticisms leveled at his office until after the final reports are released. Ranger Young confirmed that the Texas Rangers still have an open criminal investigation into Alfred Wright’s death. The FBI announced it would assist state officials if necessary, and at Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee’s request, the U.S. Department of Justice agreed in January to review state investigators’ findings. Sabine County District Attorney Kevin Dutton told the Observer he’s passed his file along to the U.S. attorney’s office. The only suspect so far is a 28-year-old black man from Jasper, who’s already facing separate charges for dealing drugs.

“Danny Young has spent most of his time trying to discredit Alfie by finding drug dealers and all that,” Douglas Wright says, “to try to do whatever he needs to do to make the picture that has been painted, to make it a full picture.” Wright believes authorities are covering up what happened to his son, and he sees officials in Hemphill are circling to protect their own. He sees Maddox and Young in that circle, and Ener, and the deputy who saw Alfred outside the liquor store that night, and the son of the liquor store’s owner, a city cop Wright saw hobbling in the field, nursing an injured leg, during the official search.

What heartens him now are the people who have helped his cause: white people from Hemphill who sound scared but tell him he’s on the right track, strangers—whatever their ultimate motivations—who lend credence to his fight and spread the word. Wright and his family are mobilizing an army of Alfred’s friends and high school classmates and Jasper church leaders and motivational speakers and American Idol fans and celebrity realtors, and he believes—he has to believe—that their work has just begun. “We’re in a fight,” he says. “We’re in a fight for justice.”

Update on August 8, 2014: In the first official word on the case in months, the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Beaumont announced the indictment of 28-year-old Shane Dewayne Hadnot of Jasper. Wright’s family has protested, saying the news is in keeping with an official cover-up. You can read more about the news here.