A Sign of the Times in San Antonio

A version of this story ran in the June 2012 issue.

China and Japan are two very different countries. The City of San Antonio knows that.

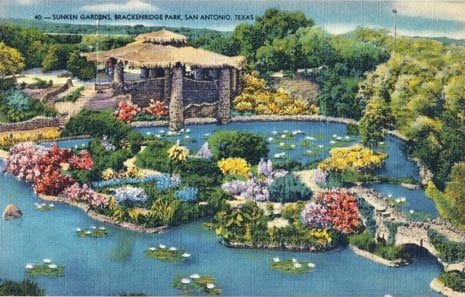

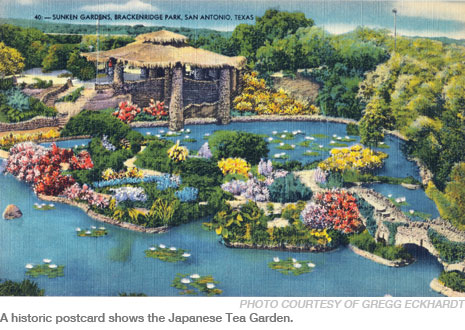

But a visitor to the Japanese Tea Garden in Brackenridge Park could be confused. A sign at the entrance to the garden, with its pagoda-style pavilion, koi pond and stunning 60-foot waterfall, reads “Chinese Tea Garden.”

It’s not a simple mistake. The story behind the sign weaves together the fates of two families, a local artist and paranoid public officials during World War II. While technically incorrect, the entry sign is historically accurate in its reflection of the reactionary wartime mentality.

It is, quite literally, a sign of the times. Today, it serves as a reminder of an attempt to rewrite the history of a San Antonio landmark.

The garden was the unlikely vision of Parks Commissioner Ray Lambert. Around 1915, he surveyed the trash-filled quarry that had operated on the site and decided it would be perfect for a Japanese-style garden with a lily pond. Lambert’s enthusiasm wasn’t met with funding, so he used prison labor to construct the pavilion and a pond laced with walkways and bridges.

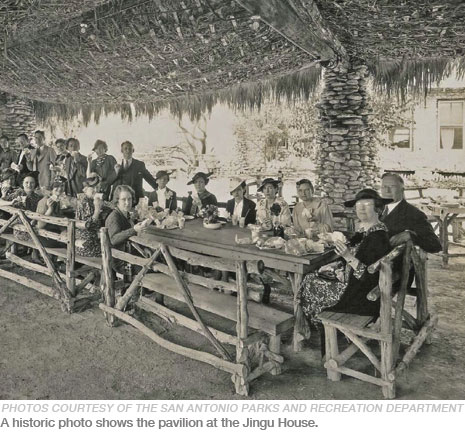

Like any good creator, Lambert realized the human element was missing from his garden. He invited Kimi Eizo Jingu, a Japanese watercolor artist, and his family to move into a house on the grounds to add authentic atmosphere. “Here tea and wafers will be served by a real Japanese lady and in real Japanese style,” gushed the San Antonio Express in October 1918. “Mr. Lambert has been successful in securing the services of a woman, fresh from the land of Cherry Blossoms, who, together with her husband and two children, will make their home right on the park, where a cozy Jap [sic] house will be built for them, and tea will be served by this little lady dressed in her graceful flowing kimono, with all the fixin’s.”

Mr. Jingu continued his artwork and also began to import tea. In 1926, the Jingus opened the Bamboo Room, which served light lunches to garden visitors. The couple ultimately had eight children, five of whom were born in the house in the garden. The first to be born after their arrival was a daughter they named Rae, after commissioner Lambert.

Surrounded by the gardens, the zoo and the river in Brackenridge Park, the Jingu children had what 86-year-old Mabel Jingu Enkoji today describes as “the best backyard anyone could ask for.” She grew up playing on the three-foot-wide lily pads in the pond, eating lemons and doing her homework in the garden, and watching performers rehearse at the nearby amphitheatre.

Once a monkey escaped from the zoo next door and appeared at the Jingu House doorway, where Enkoji fed him a cookie before notifying the zookeeper. “Every time I’d go visit the zoo after that, he’d move his lips like he was chewing a cookie,” she remembers.

Mabel and her siblings walked through the park to the public elementary school, where she was in the same grade as lifelong friend Terrellita Maverick, whose father, Maury Maverick, was a Democratic congressman and later served as mayor of San Antonio.

When they played in the garden, “[Mabel] had to wear a sign that said ‘Do not feed this child,’” Maverick remembers. “People were always giving her candy or cookies, and then she wouldn’t eat dinner.”

A German gardener and a Mexican harpist were also fixtures in the surprisingly multicultural garden. The Jingu children grew up speaking English and Spanish, not Japanese.

In contrast to this idyllic childhood, conditions were challenging for Japanese Americans in the United States. The situation in Texas was less tense than on the West Coast, where the Japanese population was larger and employment-related anti-immigrant prejudice was stronger. Perhaps this was why Mr. Jingu came to San Antonio from the West Coast; the Jingus were among only 519 Japanese Texans recorded in the 1930 U.S. Census.

While Miyoshi Jingu, Mabel’s mother, eventually earned her citizenship, Kimi Jingu, her father, never did. A 1790 federal law barring those who were not “free white persons” from naturalization wasn’t amended to allow Japanese to apply for citizenship until 1952. Mr. Jingu died in 1938.

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, conditions worsened. About 120,000 Japanese, mostly from the West Coast, were forced to live in internment camps for the duration of the war. More than half were American citizens. The nation’s largest camp for families was in Crystal City, only 100 miles southwest of San Antonio. It held more than 3,000 internees of Japanese, German and Italian descent.

Many Japanese Americans who lived inland avoided confinement in the camps but were arrested and interrogated. According to historian Thomas Walls, author of The Japanese Texans, San Antonio mayor C.K. Quin ordered interrogations of everyone of Japanese descent in his city.

In 1937, an article in the San Antonio Light had called the Jingus “one of San Antonio’s unique assets.” But after Pearl Harbor, the city perceived it had a public relations problem, if not an actual threat, in the Jingus: The showpiece city park was inhabited by the enemy. In July 1942, the city told Miyoshi, by then a widow, that she and her children had to leave. When she didn’t comply immediately, the house’s utilities were shut off.

“Evidently the city didn’t feel it was ‘safe,’ and I put quotes around ‘safe,’ for us to be there,” Enkoji says. “Though at the time I didn’t feel any different than anyone else I went to school with.”

It’s difficult to learn much about the city’s decision. The most detailed information comes from correspondence between the city manager and the parks director in 1974. The memo references a 1942 city council resolution “Authorizing and directing the City Clerk to advertise for bids for the privileges and concessions on the premises known as the Chinese Sunken Garden (formerly the Japanese Garden) for the term of one (1) year.”

Parks Commissioner Lambert was unable to advocate for the family; he had died in 1927.

Although newspaper accounts paint a bleak picture of the family’s fate, Enkoji’s daughter Peggy Nishio describes her grandmother as a warm, witty woman with a loyal cadre of friends she’d made through her children and the Travis Park Methodist Church. The church helped the family find housing, and the older children took jobs to replace the income from the Bamboo Room. Mabel, then 16, became a gift-wrapper at Joske’s department store.

“Customers would say, ‘My, you speak such good English,’” she remembers. “I’d say, ‘So do you.’”

With the Jingus gone, the city changed the garden’s name to “Chinese Tea Garden” and invited Ted and Rose Wu, a Chinese American couple in the grocery business, to take over the park concession. The entry sign Kimi Jingu had designed in the style of a torii gate, a portal marking the entrance to sacred space in a Shinto shrine, was removed and replaced with a city-commissioned entryway by Dionicio Rodríguez and Maximo Cortés. Rodríguez, whose work was already in public and private collections throughout the United States, had brought his distinctive artistic medium with him from Mexico. The work, which uses sculpted concrete to mimic the curves and texture of wood, is called “faux bois”— fake wood—or “trabajo rustico,” rustic work.

The sign, which reads “Entrance to Chinese Tea Garden” in faux bois letters, still greets park visitors today.

Barbara Wu Yu, the Wus’ daughter, a retired real estate professional in San Antonio, was old enough to work in the garden restaurant when the operation changed hands.

“The only reason we were there was that during the war, the Japanese were our enemies, so they had to be removed as the caretakers,” she says. “Because Daddy was so well known in the Chinese community and was a businessman, he was asked if he would like to take it over, and he did.”

Yu points out that, at the time, Japan had also invaded China and gotten as far as Shanghai.

Despite the awkward situation, there was no animosity between the families in San Antonio’s small Asian community. “It was strange because they were friends,” Enkoji remembers. “It affected both parties a lot. The Wus more or less apologized to my mother because it wasn’t their idea.”

Did the city perceive Chinese and Japanese cultures to be interchangeable? On one hand, despite the Jingus’ deep ties in the community, their Japanese origin instantly associated them with the enemy. On the other, the quick change to the garden’s name—without changes to its design—suggests the city leaders didn’t perceive the distinctions between the two cultures.

“People don’t really know the difference between Japanese and Chinese,” Enkoji says, “so to the public it didn’t make that much difference.”

The lack of discernment affected other Asians who felt Japan-directed wrath during the war, historian Walls explains. People wore buttons reading “I am Chinese” or posted signs at their businesses declaring “I am a loyal Filipino.”

Even today, Nishio says, “many people of non-Asian descent don’t know the different surnames and can’t distinguish Filipinos versus Japanese, Chinese or Thai. We come from distinctly different countries, and each country has characteristics that are singular to their country, but how much of the general public says, ‘Well, they’re all the same’? Probably less today, because the world has become much smaller, but back then what Texan could tell the difference?”

After the Wus left in the ’50s, the garden went through a number of changes. The café was replaced with a snack bar; for a while an aerial tram went over the garden. By the early ’70s the city was discussing an evening curfew to curb nighttime criminal activity. During this time the park was often referred to as the “Sunken Garden.”

But Maury Maverick, Jr., Terrellita’s brother and a former state representative, had launched a campaign to restore the garden’s original name. In the San Antonio Express and in correspondence with public officials, he pushed for the historical record to be corrected.

In July 1974 he wrote a letter to the editor of the newspaper urging the name change, which had been suggested by two of the Jingu sisters during a recent visit to San Antonio. Maverick sent a copy of the letter with a personal note to the director of parks, Ronald Darner, and at least one city council member, W. J. O’Connell. O’Connell replied that restoring the name seemed “fine,” and Darner told the city manager’s office the idea was “well taken.”

In 1983 the idea finally got traction when City Councilman Van Archer championed it. Archer, who lived within biking distance of the garden, had visited China.

“When I came back I got to thinking, ‘You know, there’s nothing Chinese about the place,’” Archer recalls. He researched the garden’s history and learned about the Jingu family’s eviction.

He wrote in a memo quoted by San Antonio newspapers: “I believe that officially renaming the sunken gardens will serve as at least a small and symbolic reparation for the wrongs suffered by an American minority group caught in the madness and hysteria of war.”

Maverick and Archer built their case partly on the principle of honoring the Japanese Americans who served in the war. They cited the honor of men who fought for tenets of freedom that weren’t extended to them at home. Both Jingu sons enlisted, and James received a Purple Heart as part of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, composed almost entirely of Japanese-American soldiers. The 442nd is often remembered for rescuing, against tremendous odds, the “Lost Battalion,” a group of American soldiers that in 1944 had been surrounded by German forces.

On July 7, 1983, the council voted to restore the name “Japanese.” Council member Frank Wing, himself part Chinese, had expressed some ambivalence to reporters, pointing out that many Chinese Americans also fought in World War II. He suggested perhaps calling the place the Oriental Sunken Gardens. But ultimately, the vote was unanimous.

The garden was rededicated in October 1984 during a ceremony attended by the Japanese ambassador to the United States and about 25 members of the Jingu family. City signs and documents were changed to read “Japanese Tea Garden,” but the Rodríguez entryway remained. A historical plaque was added nearby to explain the entry sign to puzzled visitors. But they still ask about it, says Caryn Hasslocher, owner of the catering company that operates the Jingu House.

“People are looking for something that really explains why the entrance of the Japanese Tea Garden is not stated as the Japanese Tea Garden. They are somewhat nonplussed because it’s not really a satisfactory answer, is it?”

The official name change wasn’t a panacea, either. A tight budget left the park’s maintenance fund short, and by the mid-’90s the garden was in disrepair. The ponds were dry, and part of the pavilion was propped up by 2x4s. Gangs and a large colony of feral cats called it home.

In 2004, the city considered privatizing the garden and the adjacent amphitheatre, a move that angered many San Antonio residents. But the only group that came forward was the San Antonio Parks Foundation and its membership group, the Friends of the Parks. With a combination of public and private funds, the group commissioned a master plan and restored the ponds, waterfall and walkways.

The garden reopened in March 2008 with a ceremony attended by Mabel Jingu Enkoji, by then one of three surviving Jingu children. Work (and fundraising) continued with the restoration of the Jingu House. For many years the house had been a restroom and storage facility, but it reopened in October 2011 as a tearoom and lunch café decorated with historic photos of the garden and the Jingu family.

Today, the garden is lush with green plants and flowers of all colors: indigo, scarlet, lavender, tangerine, ivory. Although the waterfall is turned off because of the drought, the ponds are full and are home to fat koi who smack their lips against the water’s surface. On weekends children scamper over the stone bridges, dodging brides taking wedding portraits. In the evenings, young couples sit on the rock outcroppings and listen as mockingbirds salute the sunset.

Will the sign remain?

Carlos Cortés, Dionicio Rodríguez’s great-nephew and Maximo Cortés’ son, learned the art of “trabajo rustico” and continues the family craft in his studio just south of downtown. He says that several years ago a parks group approached him about designing an entry that would be significantly larger than the current entrance and read “Japanese Tea Garden.” The cost was prohibitive, and the idea seems to have been shelved.

He says he can look at the existing sign two ways.

“It was definitely wrong that they pushed those people out, because that wasn’t fair. I’ve had people tell me, ‘That’s an injustice. You should really change it to say Japanese Tea Garden.’”

He shakes his head. “But I would not touch my great-uncle’s work to change it, because it wouldn’t be fair to my great-uncle or to his work. I don’t ever want to see it changed, even though it’s politically incorrect.”

Terrellita Maverick would like to see a compromise.

“They ought to take it down and have a picture of it,” she says. “The marker should say ‘For 50 years or more there was a sign that declared that this was the Chinese garden, and finally, at long last, it is properly named.’”

But Peggy Nishio says, “[The sign] adds to the sense of, ‘Wow, that’s disheartening that they changed it so quickly [after the start of World War II].’ My feeling is that it’s part of history.”