Party Crasher

Can Houston's king of right-wing talk radio bust into the Texas Senate?

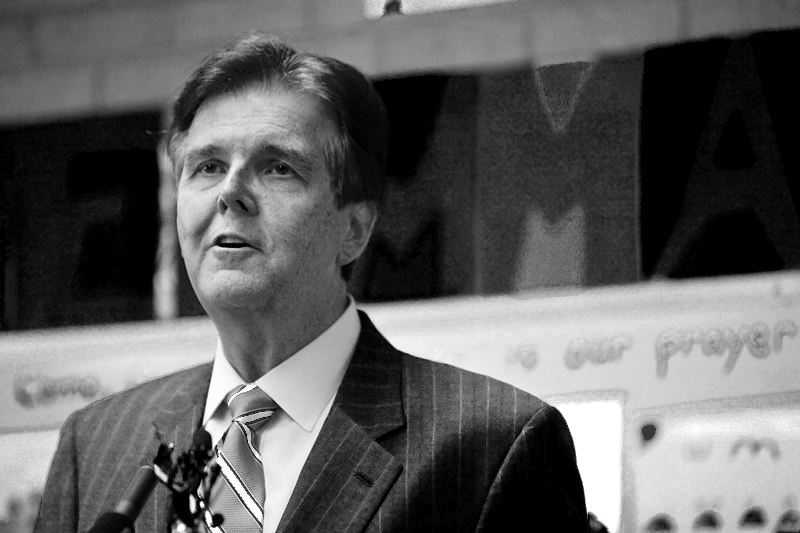

Above: Dan Patrick

It’s a bright winter morning at the Champions Golf Club in Northwest Houston. A touch of frost flecks the fairways as golfers make their way toward the clubhouse. This hardly looks like a political hot spot. Yet, at a well-appointed function room here, a battle for the soul of the Texas Republican Party is on the breakfast menu.

Some 30 members of the Northwest Houston Executive Club are gathered to hear Dan Patrick, a radio personality-turned-politician who, handicappers say, is the candidate to beat in a four-way race for an open seat in the Texas State Senate. Patrick is up against two members of the Texas Legislature—Reps. Peggy Hamric and Joe Nixon—as well as former Houston city councilman Mark Ellis in the March 7 primary. If no candidate clears 50 percent, a runoff is set for April 11. The winner in this hyper-Republican district in the sprawling Houston suburbs is expected to coast past the Democratic candidate in November.

Tall and lanky with a ready smile, Patrick sports a thatch of brown hair, parted toward the middle in the style of an Irish bartender. At 55, despite some graying at the temples, he projects a youthful demeanor. A graduate of the University of Maryland Baltimore County, Patrick—whose given name was Dannie S. Goeb—came to Houston from WTTG in Washington, D.C., in the 1970s as a local sportscaster. He went bankrupt as a restaurateur in the mid-1980s. Then he reinvented himself, becoming owner of a radio station, a millionaire, and the host of a Houston drive-time talk show on KSEV-AM (700).

For the past 17 years, Patrick’s show has filled the airwaves with a volatile brew of talk-radio populism. He combines a take-no-prisoners stance on pocketbook issues—railing against rising property taxes, public subsidies of sports arenas and ballparks, and what he depicts as out-of-control government spending—with an aggressive, born-again Christian message on social issues such as abortion and gay marriage. In 2003 he formed Citizens Lowering Our Unfair Taxes, or CLOUT. During the legislative session that year, busloads of CLOUT protesters journeyed to the Capitol in Austin to rally for a cap on property tax appraisals.

At the golf club breakfast, in a practiced and smooth delivery, Patrick inveighs against the “Robin Hood” plan that takes money from property-wealthy school districts and redistributes it to poorer ones. He promises to put an end to politics-as-usual in Austin, attacking the power of lobbyists as well as the clubby atmosphere of the Texas Senate. Taking a stand that sounds uncontroversial here but is jolting to Austin insiders, he calls for elimination of the Senate’s two-thirds rule, which requires the consent of 19 of 31 senators before a bill can be considered on the Senate floor. The rule tends to encourage cooperation and collegiality between the GOP and the Democrats; to Patrick it requires the Republican majority to bargain needlessly with the enemy.

But Patrick saves his most hard-edged oratory for illegal immigrants. He blames them for a rising crime rate, overcrowded schools, an overburdened health-care system, and runaway growth in the state budget. “The number one problem we are facing,” he tells audiences, “is the silent invasion of the border. We are being overrun. It is imperiling our safety.”

“The crime rate is soaring,” he says, “and most of it can be tracked to illegal immigration. There are terrorists and drug runners coming into Texas and the sheriffs in 15 border counties are being asked to stop them with only a .45 on their hip and a shotgun in the trunk. They’ll tell you it’s the federal government’s responsibility,” he adds, “but the cavalry is not coming. It’s up to us to protect our borders.”

Illegal immigrants, moreover, are walking pathogens. “They are bringing Third World diseases with them,” Patrick asserts, citing “tuberculosis, malaria, polio and leprosy.”

Patrick’s message goes down well at the golf club with this largely middle-aged, white-collar, mostly male crowd. They include: a car dealer, a commercial real-estate broker, a sales rep for an office-furniture concern, the owner of an auto-repair shop, an insurance agent, a jeweler, and a banker. “I liked what I heard and agreed with Dan’s platform,” says Bob Steele, a retired ExxonMobil executive.

Several snap up free copies of The Second Most Important Book You Will Ever Read, Patrick’s inspirational book on reading the Bible, some of which he autographs. (A brief bio of Patrick on the back flap reports that his “number one goal in life is to serve the Lord in everything he does, spreading the Word of God as Jesus commanded.”)

As audience members depart, many carry yard signs, bumper stickers, and campaign literature. One Patrick loyalist vouches for his good character. “Dan’s the kind of guy,” says Steve Drake, an investment counselor in Houston, “that you’d call at three in the morning when you’re stuck out on the highway with a flat tire.”

Lying mostly outside Houston city limits in the northwest quadrant of Harris County and part of Waller County, Senate District 7 includes the communities of Spring, Katy, Cypress, Tomball, Jersey Village, and the Memorial Villages. Only about a quarter of the district is within Houston proper. The Almanac of American Politics describes this area as “a zone of rapid metropolitan expansion and growth, of commercial office space and upscale residential subdivisions rising on land that once held roadside stands and barbecues and unpainted farmhouses with water pooling on low swampy fields.”

Amid tall stands of pine trees, many of the tony neighborhoods here could double for Wisteria Lane of “Desperate Housewives” fame. The district has roughly 700,000 residents and, according to Capitol Inside, a political newsletter, there were 409,653 registered voters as of the 2004 election. In recent presidential elections, it has divided 75 percent to 25 percent in favor of the GOP, placing it among the most Republican districts in a Red State.

Patrick has high name recognition among likely voters, the result not just of his radio exposure but of national television appearances on Fox News, MSNBC, and other media outlets. His work on religious and charitable causes helped win the support of the actor Chuck Norris, known for his role as “Walker: Texas Ranger.”

In a season with no significant contested statewide races on the Republican ballot, the race for the seat vacated by retiring Sen. Jon Lindsay is emerging as a bellwether election. The winner will help determine the direction of the Texas GOP and, since Republicans rule the roost in the Lone Star State, the trend of state politics and policy. If Patrick wins, moreover, it may position him for higher office.

For his most ardent supporters, Patrick’s campaign is something of a crusade, generating excitement and passion. “Let me say from the bottom of my heart,” Guy Lewis, a cosmetic dentist, told guests as he played host to a reception for Patrick at his Spring home, “that I admire Dan and he is making this race for all the right reasons. When he goes to Austin, he won’t be influenced by the wrong people.”

Patrick’s earnestness may give him an air of credibility when he’s at his best. But on the stump there’s also an inflammatory and even paranoid style at work—and not much fact-checking. On the threat of immigrants bringing “Third World diseases” across the border, for example, Patrick’s information doesn’t check out.

Tom Betz, a physician with a master’s degree in public health who serves as the top epidemiologist at the State Health Services Department, says there is not a known case of polio in the Western Hemisphere “and we haven’t seen it in decades.” Malaria is a tropical disease spread by the anopheline mosquito. It is easily treated and remains “a rare disease in Texas and not a huge problem.” Leprosy is known today as Hansen’s disease and “we have no more than 50 cases a year that are reported, but it’s not on the rise.” As for TB, “We’ll have 1,500 or so cases in Texas this year, which might be a slight increase, but we’ve got very effective TB-control programs in every local health department in the state.”

Patrick is energizing a new group of primary voters. Many are from evangelical churches or are CLOUT members, or are avid listeners to his radio show. Even some disaffected Democrats are responding, Patrick says. Recently, Patrick insurgents have been taking over positions as precinct chairs. So much so that, bolstered by a bevy of new recruits, Patrick claims endorsements from more than 100 Republican precinct chairs in the senatorial district, as well as backing from the State Republican Executive Committee.

At the same time, however, his candidacy is loathed by a significant segment of the party regulars, as well as by powerful business interests. The voters who used to be called “rock-ribbed” Republicans, the party stalwarts who once were the backbone constituency for the late Senator John Tower and former President George H.W. Bush, now find themselves disdained by Patrick as “RINOs,” shorthand for “Republicans In Name Only.”

The acrimony on both sides is palpable. “He’s a radical right-winger,” says Kay Shillock, past president of the Greater Houston Council of Republican Women and a longtime party activist. Shillock is self-assured and well dressed; she wears a flowing prismatic scarf about her neck, and an “I’m for Peggy” button. Interviewed after a candidates’ forum sponsored by a Republican women’s group, Shillock says that she no longer calls herself “conservative;” these days, she prefers the moniker “traditional Republican.”

Shillock expresses irritation that during Patrick’s appearance at the political forum he made several references to his born-again religious convictions. That, she thinks, could have been a turn-off for any Jewish voters who might have been present. True Christianity, in her view, does not mean foisting religious beliefs on others or legislating morality. Though she is a self-described Protestant, Shillock has little truck with fundamentalists who inject their religious beliefs into the political process. “I have a problem with that,” she says. “I don’t think it has a place in the political spectrum.”

Her anti-Patrick sentiments are shared by Senator Lindsay, the 70-year-old incumbent and former chief executive of Harris County. “I think he would be terrible in the Senate,” Lindsay says of Patrick in a candid telephone interview. “He’d be a difficult person for the lieutenant governor and the leadership to work with. I don’t think his agenda would be good for the state of Texas.”

The senator holds little regard for Patrick’s proposal to make the Senate operate more like the House and enact legislation by a simple majority. “I think the two-thirds rule is something that keeps the Senate stable,” he says. “You can’t just steamroller people. It makes sure that the minorities are represented.” By “minorities,” Lindsay explains, he doesn’t mean members of ethnic groups but “the rural guys and members of the party out of power.”

It also galls Lindsay that Patrick has made illegal immigration a front-and-center issue in the campaign. “This is really not a state issue,” Lindsay says, “and you don’t hear him explain how he’d fund it. He’s misleading folks into thinking it’s a black-and-white issue that’s easy to fix, but it would be expensive.” Although Lindsay would have preferred to stay neutral, he’s now backing Hamric. “I’m not a Dan Patrick fan,” he says. “He’s an extremist. And if Joe gets into the runoff,” he adds of Rep. Nixon, “I’ll support Joe.”

But Hamric has emerged as the senator’s favorite. Lindsay worked closely with her on knotty problems involving municipal utility districts and groundwater and surface-water issues back when he was Harris County’s chief executive. “And I’ve worked with her at the Legislature,” he adds. “She knows the district well and knows what needs to be done, and she’s not a carpetbagger.”

Was he branding Patrick a carpetbagger? “There’s no telling where Dan Patrick’s coming from,” Lindsay says.

Rep. Joe Nixon has assumed the role of Patrick’s chief antagonist. He regularly lambastes Patrick for continuing his radio show after his October 17 campaign announcement. Patrick signed off the air in late December, just days before the January 2, 2006 filing deadline. Under a rule of the Federal Communications Commission, his opponents would have to be given equal time if he continued broadcasting. (Patrick is reporting in-kind contributions from the radio station valued at $119,000. He has also lent his campaign more than $300,000, according to his campaign manager, Court Koenning.)

Nixon has all but accused Patrick of carpetbagging as well, noting at every opportunity that “one candidate in the race” bought a condo in the Senatorial district in September 2005, which narrowly qualified him for residency in the district. “If you don’t want to be my neighbor,” Nixon says, “why would I trust you to represent me in Austin?”

Big and burly and occasionally brusque, Nixon tells voters that he’s the one who has been laboring in the Republican trenches on issues that Patrick has only talked about. It was he, the 49-year-old Nixon says, who proposed legislation to specify citizenship on Texas driver’s licenses and to block “sham marriages” by foreigners. It was he, Nixon says, who introduced a bill to restrict the growth in property-tax appraisals to 3 percent each year—legislation that passed the House only to fail in the Senate. Indeed, Nixon says on the campaign trail that he voted 250 times to cap property taxes. “I’m the guy,” he says, “who has been doing the work in the House that everybody else is campaigning on.”

It is hard to gauge whether voters are warming to Nixon’s argument that his legislative record merits him a Senate seat. He faces hurdles, among them that his House district is only partially located in the Senatorial district, which means that he must introduce himself to a large chunk of primary voters. But as the best-funded candidate in the field, he’s got the war chest to do it.

A graduate of Texas A&M in economics and a lawyer, Nixon serves as chairman of the House Civil Practices Committee, where he has built a reputation as a hard-nosed, political tough guy (“There’s a new sheriff in town,” he famously told trial lawyers) and a leading champion for business interests. He pushed a 2003 law that proponents call “tort reform,” which places draconian restrictions on a Texas citizen’s ability to seek civil damages and jury awards for personal injuries and other wrongs.

As the darling of big business, Nixon raised $477,000 in the last six months of 2005, according to the Houston Chronicle. And political observers expect him to raise and spend $1 million on advertising—billboards, direct mail, and radio and television spots—promoting his image as a person with “integrity, leadership, and results.”

But it may be a hard sell. At the same time that he has fenced off the courthouse to people seeking redress for grievances, Nixon has been demanding compensation for wrongs done unto him. In 2003, Nixon got roughly $13,000 from Farmers Insurance Group in a claim for mold damage to his residence. When an employee of the insurance company charged that the payment was made because of favoritism, she was fired. Whistleblower Isabelle Arnold later was awarded $260,000 in lost wages by a California jury, according to the Houston Chronicle.

Richard Murray, a political scientist and elections expert at the University of Houston, thinks Nixon’s reliance on advertising media and his roughhousing with Patrick may contribute to a negative image. “And he’s got some heavy baggage from the tort legislation he carried, but then benefiting himself from lawsuits.” (Nor does Nixon’s baldness help, says Murray. “There are exceptions, but not many bald candidates have fared well since President Eisenhower,” Murray says.)

There are, of course, kinder and gentler moments on the campaign trail when Nixon can come off as “gruff but lovable,” in the view of Jon Taylor, a political scientist at the University of St. Thomas. At a recent campaign forum a questioner observed that Texas shamefully ranked 48th in the country in spending on mental health and asked the candidates how they could justify cutting taxes when, as Houston news media report “every other day,” people suffering from mental illness regularly commit acts of violence that intervention and treatment could have prevented.

During the most recent legislative session, Nixon noted, he authored a bill to require that insurance companies cover mental health problems at the same reimbursement rates as physical ailments. And he declared that he has been trying to secure earlier treatment for the mentally ill in Houston through greater funding for the Texas Department of Mental Health-Mental Retardation. “There are people—even Republicans—working for that in a compassionate way,” he said.

Mark Ellis, at 44, is the youngest candidate in the field. He exudes the collegiate heartiness and good-natured charm of a student body president. Educated at a Jesuit high school and the University of Houston, where he majored in political science, Ellis is a certified financial planner. In his tenure on the city council where he chaired the Fiscal Affairs Committee, he compiled a record of winning tax reductions for homeowners amounting to $60 million. One Austin lobbyist familiar with Bayou City politics, says: “Around city hall, they say he’s a class act.”

Ellis also gets credit for an innovative proposal to require homebuilders and contractors to hire private-sector building inspectors—certified, licensed, and monitored by the city—rather than saddle the municipality with more bureaucrats. “With our civil service laws, we could hire inspectors in a housing boom and have them on the payroll permanently,” he says, “and that wasn’t cost-effective.”

Last November, however, Ellis floated a trial balloon that a scathing editorial in the Houston Chronicle labeled a “political stunt.” He suggested that the police should enforce immigration laws and that the City of Houston should check on the immigration status of persons receiving taxpayer-funded social services. Chronicle editorialists saw it as Ellis’s “transparent tactic to win support for his senatorial bid.”

Ellis is drawing support from the Houston police, whose union has endorsed him, but his campaign has had difficulty raising money, reporting less than $200,000 in contributions over the past six months. The fact that most of the Senatorial district is situated outside Houston proper and that the district’s suburban voters remain distrustful of city politicians also put him at a disadvantage. But Ellis, for his part, pluckily contends that, although city residents make up only 30 percent of the electorate, they turn out in higher numbers in primary elections.

Even so, he is not given much of a chance by party professionals. His presence in the race, though, could be just the ticket to deprive any candidate of 50 percent, thus forcing a runoff.

Peggy Hamric has laced up a pair of brand-new running shoes, driven her sport utility vehicle nearly an hour north of her House district, and commenced block-walking in the town of Spring. In a pleasant neighborhood of tall trees, neat lawns, and large but not imposing houses, she rings doorbells, passes out campaign literature, and chats with prospective voters.

Accompanied by a campaign volunteer with a computer printout of names and addresses, Hamric is an adroit, experienced campaigner. She senses quickly whether to engage a prospective voter in conversation and, if so, whether talk should be about the gentle Texas winter or politics. Yet few of these households actually merit her attention. Rather than knock on every door, Hamric only calls on domiciles where, according to her campaign’s database, a proven primary voter dwells. That means neglecting scores of handsome homes, smiling at a stray citizen on the street, but visiting only the targeted audience. “It’s totally retail politics,” she says.

Many people are not at home, so Hamric writes “Sorry I missed you” on a leaflet and hangs it on the door. Yard signs for Dan Patrick are abundant and Hamric usually pays them no mind. But if a Patrick-backer is on her list, she gamely strides up the walk—yard sign or not. “If I can’t be your first choice, I hope you’ll make me your second choice,” she tells one homeowner, who seems doubtful but polite.

Even among these likely voters, few seem aware of the campaigns or the date of the election; in a number of instances it is news that the incumbent senator is retiring. “We know Jon Lindsay very well because he goes to church with us,” a couple standing in their driveway tell Hamric. “Well, he’s endorsed me,” Hamric says, which impresses them. When they announce their support, Hamric exclaims: “I knew this was a smart household” and enlists them to put up a yard sign.

At 65, Hamric is a 14-year veteran of the Texas House of Representatives and a key cog in a Republican leadership that has dominated the body in the last two sessions. She has made a name for herself as not only an energetic team player but as a person liked on both sides of the aisle. As chairwoman of the House Administration Committee, of course, it behooves a House member to get along with her: she is in charge of assigning office space, furniture, and even parking places.

A graduate of the University of Oklahoma who grew up in Portales, N.M., not far from the Texas border, Hamric has won passage of legislation affecting women’s health issues, such as requiring insurance companies to pay for at least 48 hours of hospital care for mastectomy patients. She has also made criminal justice and public safety a concern, authoring a bill that revoked the practice of mandatory releases and instituting a review process.

Her office specializes in constituent services—helping people negotiate their way through government bureaucracies, assisting communities with siting landfills and dumps, or keeping them out. She also has taken a keen interest in promoting transportation and public works. “The suburban area outside Houston would never have happened without the infrastructure,” she says, adding: “A lot of people move to this area for the good schools and the community college system.”

Before her election to the Legislature, Hamric was a homemaker, substitute teacher, and the president of her local women’s Republican club. In 2002, she oversaw the GOP’s get-out-the-vote drive in Greater Houston. “I’m part of the movement that built thisparty,” she says.

The party network, as well as a steady stream of endorsements from elected officials, could make her the best-positioned candidate to face Patrick if there is a runoff. In addition, political insiders say that the strength of Republican women’s groups in Houston should never be underestimated.

Patrick’s views and “shock jock” edginess—an anti-abortion, former sportscaster who once broadcast his radio show from a doctor’s office while he underwent a vasectomy—are not easily embraced by many women. “About three-quarters of the Republican women’s clubs are going for Hamric,” asserts Shillock, the Republican party activist. Demographic trends, moreover, could provide her with a political tailwind. “Hamric benefits from the fact that about 53 percent of the voters are women,” says political scientist Murray. “There are more women than men in their 70s and younger women are better educated than men and more likely to vote.” Adds a longtime Harris County Republican leader: “Republican women are very active and they yak—and if they’re talking, it gives a candidate good word-of-mouth.”

If elected, Hamric would be the first Republican woman to represent Houston in the Senate. Should that happen, there will be a welcoming committee. At least a dozen Senators served with her in the House and those relationships, she asserts, will aid her, the district, and Houston. “I’ll be able to work with the Senate as well as with my former colleagues over in the House,” she says.

Only about 40,000 persons are likely to go to the polls in the Senate District 7 primary, says a Republican Party source close to the Harris County Clerk’s office.

Based on the number of Republican voters in the 2004 presidential election, that would be about 13 percent of the district’s pool of registered voters who tend to vote Republican. An even smaller segment of the electorate is likely to decide the runoff, should one occur. That means that the most activist and intensely committed voters in the district will decide who represents nearly three-quarters of a million people in the state Senate. Using sophisticated marketing strategies, the campaigns are targeting the same narrow group and bombarding them with appeals to vote.

“In a big metropolitan area,” says Murray, “the media stays busy and they don’t cover the race very well. Hardly anybody knows what state Senate district they live in, so it’s become an election among insiders.” Among those most likely to cast ballots, Murray says, are older Anglos who are ideologically conservative and connected to the politically active churches, which will prod their congregations to go to the polls. That sounds like a natural constituency for Patrick and his CLOUT group, which in the weeks leading up to the primary were smelling victory.

Patrick says that, if elected to the Senate, he will resume his talk show, broadcasting from the Texas Capitol. Ethical issues aside (there are strict rules barring elected officials’ trading on their position as public servants for profit), that could further raise his profile and make him a major figure in the conservative wing of the Republican Party.

It’s just one seat in the Senate, but the stakes are high for Republicans. If the field narrows as expected and the race turns into a head-to-head slugfest between the traditional Republican wing of the party and the conservative wing, money will pour into the runoff from all directions.

“Patrick is essentially an entertainer,” Murray says. “It’s going to be terrific political theater.”

Paul Sweeney, a freelance writer living in Austin, is a longtime Observer contributor. He has worked at Texas newspapers in Corpus Christi and El Paso and has written for The Boston Globe, The New York Times, and Business Week.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the name of the top epidemiologist at the Texas Department of State Health Services. His name is Tom Betz, not Tim Metz. The Observer regrets the error.