The Houston Kid

Writing from the Roots.

Success made Rodney Crowell,but in a roundabout way. The Texas musician, known as a songwriter’s songwriter, has written a memoir about his childhood in Jacinto City, a working-class neighborhood on the Houston Ship Channel. Crowell’s literary voice is witty and down to earth, but Crowell had to swing in the opposite direction before he came back to his roots. Some people have to hit bottom to find themselves, but with Crowell it was the opposite. After 10 years of making his name as a songwriter for people like Jerry Reed and Emmylou Harris, Crowell hit it big in 1988 with one of his own albums, Diamonds and Dirt. Five songs on the album went to No. 1 on the charts, but Crowell wasn’t comfortable in his success.

CROWELL: It felt good at first. The first single off of Diamonds and Dirt was a duet between myself and Rosanne Cash called “Such a Small World.” It went straight to No. 1, and I thought, “Wow this is really validating.” But I didn’t expect the album to become such a commercial success, and it made people turn and look at me in a different way.

I started creating a persona, with the bolo tie and the tight jeans. I didn’t wear the cowboy hat. But you know Dwight Yoakam just does that a lot better than me. He turned it into a sexy persona. Dwight Yoakam has that knack, and I just didn’t have that. I see him doing it, and it seems real. I saw me doing it, and it didn’t seem real.

The moment where I realized that I wasn’t the artist that I wanted to be actually took place at a cocktail party in Nashville, Tennessee. It was one of those country music events; I was nominated for, maybe, vocalist of the year or something. I walked in, and all eyes turned to me, and I just felt like the emperor had no clothes. I just felt empty. I was thinking, “Wow, how do I be the guy that they’re looking at? How do I embody whatever it is they’re projecting on me?” And at that moment I realized if I buy into this and start trying to manufacture an image of what I think people see, it’s gonna be the death of the artist. My instinct for survival was telling me, “Oh, you gotta change this!” It really was an instinct for survival. Oh, I’m becoming fake, and if I stay with this, I’m not gonna create anything lasting. Self-consciousness is the enemy of performance arts.

The record companies pressured Crowell to replicate the sound of Diamonds and Dirt, but his heart wasn’t in it. In 1994, he took a break to simplify his life. He let go of the cook and housekeeper. He started staying home and driving his kids to school. He stopped playing music, and he started writing the book that would become Chinaberry Sidewalks.

CROWELL: That book started forming inside of me around 1997-98 when I was being quiet. I knew it had to come out of me, and I knew I had to dedicate myself to figuring out how to create it, how to write it. I can write songs instinctively, but I had to actually consciously learn how to write sentences. And it was guesswork for a long time.

The notion that I had to write this book sustained me when I just had no idea what I was doing. There are some things you just know. You know when you love somebody when you see them the first time. Love at first sight happens all the time, and you just know. You can’t explain it. I just knew that first time it tugged at me, “I have to write a book.” With songs, it’s often inspiration coming to me and I know what to do, “I’m gonna write this song.” But to write a book, it just grows up organically from inside of you, and you know you have to tell this story, and you figure out some way to do it. It took me a while. The most challenging part was stamina and to have the courage and the faith to spend a month on one paragraph, to get a month deep in one paragraph and not be able to unlock its mystery. Then, you know, after a month’s work, you remove two words, and there it is. Strange how you realize those two words were blocking the whole process. It’s a beautiful life, it’s a monastic existence, and I find it suits me. I kind of thrive in that singular existence of getting up every day and working on writing, and then in the afternoon go ride my bicycle for a while, and then hang out with my wife in the evening, get up and do it again. It’s a good life, a really good life.

Crowell worked on the book for more than a decade. After a five-year hiatus, Crowell released The Houston Kid in 2000. The songs were semi-autobiographical and contemplative. None aimed at mainstream country radio. The album marked a new sound for Crowell.

Crowell’s book, Chinaberry Sidewalks, is written in the same vein. Crowell takes an unvarnished look at his childhood in Jacinto City. His folks are the types who get drunk and take their kids for a ride during a hurricane, but Crowell’s love for them comes through on the page.

EXCERPT FROM CHINABERRY SIDEWALKS: Not long after my second birthday, Hank Williams made his next-to-last public appearance at Cook’s Hoedown, East Houston’s premier hillbilly nightspot. Rejecting the notion that I was too young to enjoy the experience, my father appointed me his preferred companion for the evening. Hoisted high on his shoulders, my legs straddling his neck, I felt my senses dawning in this new world like the first few pieces being fitted into a puzzle. The eddy of cool air wafting down from overhead awakened the feeling I was somewhere very different from my usual surroundings, the hush of anticipation in the audience stirring the suspicion that I was part of something incomprehensibly great. A thunderous man-made roar tested the building’s rafters for structural weakness and overwhelmed my fledgling sensory receptors even further, but somehow I was made to understand that this kaleidoscope of sound, color and chaos was nothing I need fear. And then there was the light. Two weeks shy of fading away forever in the backseat of a powder-blue Cadillac convertible, Hank Williams was suddenly spotlit and burning on center stage, the embodiment of the lone flaming star. Visions of a distant paradise bobbed in the wake of his brilliance. I’d have joined the light then and there were it not for the scent of hair tonic and Old Spice aftershave that tethered me to my father’s shoulders.

The pulse of the music matched my beating heart perfectly, and I took comfort in this. And yet it’s the memory of my father that holds in place the memory of seeing and feeling a Hank Williams performance.

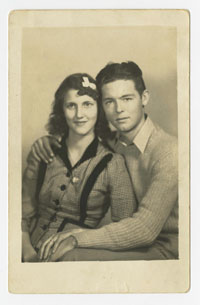

My father idolized him, and reminding me I once saw “ole Hank” sing was something he never tired of. It was the part of his legacy he savored the most. Knowing he’d exposed his only son to the greatness in another man that he imagined in himself served to soften the hard fact that his own dreams would never materialize. Hank Williams was what my father wanted to be—a Grand Ole Opry singing star. Taking me to see him perform was his way of saying, Look at me up there on that stage, son, that’s who I really am. This is the truest picture of my father that I own, though at times I strain to see it.

Rodney Crowell and his dad, J.W. Crowell photo courtesy Rodney Crowell

Crowell tells the history of his parents, from their hardscrabble childhoods through their 50-year marriage. It’s a portrait of alcoholism, bad decisions and redemption, but Crowell is never judgmental or condescending. It’s a testament to Crowell’s skills that this portrait never descends to a white-trash stereotype.

CROWELL: I knew right away that the most vivid material I had were these blessedly tragic and crazy and funny and beautiful and heartbreaking and sweet stories of my childhood. I had people say, “How can you love your parents?” I’m like, “How can I not love my parents! Look what they gave me!” What a gift for me to be able to experience these two absolutely over-the-top crazy people who find a way to reel their lives in and actually stay together 50 years.

I realized pretty early that if I was going into the really sort of despicable things my father did, and if I tried to manipulate the reader to feel sorry for me or to draw attention to myself, then it would have become all stereotype. But my goal was to get you to love them the way I love them. I knew if I stayed with that, then there’s a good chance that I wouldn’t make stereotypical characters out of them. Also, love and humor are so close, you know, and when you’re really trying to capture love, humor is so close and accessible. Often times I found it very easy to describe despicable things either my parents were doing in a very funny way because, to me, they were funny. It’s like “What on Earth are you thinking!” They had good hearts. They were good people. They were just misdirected.

I realized pretty early that if I was going into the really sort of despicable things my father did, and if I tried to manipulate the reader to feel sorry for me or to draw attention to myself, then it would have become all stereotype. But my goal was to get you to love them the way I love them. I knew if I stayed with that, then there’s a good chance that I wouldn’t make stereotypical characters out of them. Also, love and humor are so close, you know, and when you’re really trying to capture love, humor is so close and accessible. Often times I found it very easy to describe despicable things either my parents were doing in a very funny way because, to me, they were funny. It’s like “What on Earth are you thinking!” They had good hearts. They were good people. They were just misdirected.

My mother’s wicked, wicked sense of humor was really redeeming, and her indomitable spirit that even my arrogant, egocentric father couldn’t ultimately hammer down. It was a big spirit. And my father just had this big heart. He was this big-hearted guy who just needed adulation so bad that he got tricked into thinking that he needed adulation more than he needed to give this big-heartedness that he had. He was a very generous guy, but he just needed steady attention. If he didn’t get it, he found a way.

The truth of the matter is, my mother and my father and I were white trash when you get right down to it. It was a white trash house there, and the lives we were living were white trash. The redeeming thing about my parents is that they were pure white trash and they evolved out of it. They became pretty evolved people.