Texas Border Sheriffs: There is No Crisis and We Don’t Want Trump’s Wall

Despite Trump’s attempt to paint the Texas-Mexico border as a war zone, border counties are safer than the president’s own backyard. And local lawmen don’t believe a wall will do any good.

President Trump visited McAllen earlier this month to drum up support for spending $5.7 billion to build more border wall segments on the U.S.-Mexico border. He staged a press conference surrounded by piles of confiscated drugs, guns and cash, describing the situation at the border as “a national emergency.” With the government partially shut down over Trump’s funding dispute with Congress, the president is trying to prove that there’s a new, growing “crisis” on the border to pressure Democrats to cave. But law enforcement leaders in at least two border counties, including the sheriff who patrols McAllen, say the picture Trump is painting of the Texas borderlands is inaccurate.

Hidalgo County Sheriff J.E. “Eddie” Guerra, who is in charge of policing the largest and most populous county in the Rio Grande Valley, said that crime rates in his county are at record lows, and that illegal immigration has very little effect on the safety of residents. Meanwhile, Brewster County Sheriff Ronny Dodson, who is responsible for policing the largest county in Texas, said he doesn’t support the construction of a wall along any part of the 192-mile stretch of border in Brewster County, which includes Big Bend National Park.

“Because we’re on the border, the perception is that there’s murders every day and there’s shootings every day. Yet here in our county, we don’t have that going on. It’s very, very safe,” Guerra told the Observer.

But don’t take the sheriffs’ word for it. In 2017 (the latest year for which data is available), there were 4.4 murders per 100,000 people in Hidalgo County — about half the rate of other metro areas in Texas and a quarter of the murder rate in Washington, D.C. It’s also lower than the 6.3 murders per 100,000 people in 2017 in Palm Beach County, Florida, where Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort is located.

In addition to fewer murders, the violent crime and property crime rates in Hidalgo County are less than half of what they were in 1999. Guerra, a Democrat who has lived in the RGV his entire life, said the majority of immigrants entering the county without papers are Central American asylum-seekers fleeing violence and poverty who turn themselves over to Border Patrol agents as soon as they can.

“They’re averaging, here in the Rio Grande Valley sector, about 600 apprehensions a day. Most are family units. These family units and unaccompanied children pose exactly zero security threat in the county,” Guerra said.

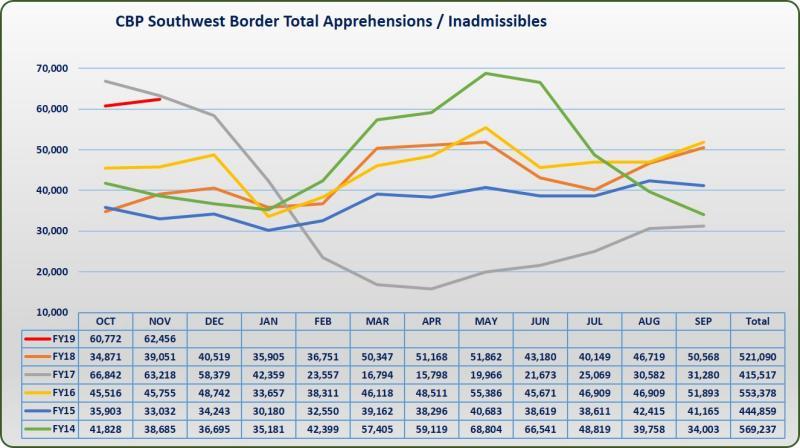

Guerra’s observations are reflected in Customs and Border Protection (CBP) data: Since September, families and unaccompanied children have made up more than half of Border Patrol apprehensions. And apprehensions across the entire U.S.-Mexico border are down significantly over the last 20 years, with the number of migrants apprehended in the Rio Grande Valley falling by 44 percent from 1997 to 2017.

“This is what’s been going on for years. I’m not going to argue that we have a secure border, because we don’t, but to say that all of the sudden we have a crisis going on is wrong,” Guerra said.

Five hundred miles northwest, Brewster County Sheriff Ronny Dodson says he’s seeing a similar trend. Dodson, a Democrat who has been in the post since 2001, said the migrants apprehended in his county tend to be asylum-seekers from Central America fleeing some of the most dangerous countries in the world. In 2017, the number of apprehensions in the Big Bend sector, which includes Brewster County, was less than half of what it was in 2000.

“The Guatemalans and Hondurans are not carrying drugs,” Dodson said. “For the most part, they just go on through.”

Trump has claimed in speeches and tweets that a wall would “have a huge impact on the inflow of drugs coming across” the border. But data shows this is unlikely. The majority of hard drugs, like cocaine, fentanyl and heroin, are smuggled through the mail or through ports of entry, not by individuals crossing the border illegally. The amount of marijuana seized along the U.S.-Mexico border has dropped in recent years, especially in California, where voters legalized the sale of cannabis in 2016. In other words, a wall wouldn’t do much to stem the trafficking of drugs into the United States; however, it would require the federal government to seize land along the border, a move Dodson vehemently opposes.

“We have a river, and we don’t want to cut ourselves off from that river. I know there’s a better way,” said Dodson, who told the Observer in 2014 he wished politicians like Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick would “shut up” about the border.

“These family units and unaccompanied children pose exactly zero security threat.”

In Hidalgo County, about 20 miles of wall already exist. Funding for 33 more miles of border wall (25 of which will be in Hidalgo County) was approved by Congress in March, and construction is slated to start as early as next month. Guerra said that spending billions to build more border wall in his county would be a waste, partially because migrants would still find a way across.

“First of all, we already have one physical barrier, that’s the Rio Grande. To cross it, [migrants] use a raft. To cross a 22-foot-high fence, they’ll use a ladder,” Guerra said, adding that federal money would be better spent on improving technology at ports and hiring more Border Patrol agents.

Both Guerra and Dodson believe that hiring additional qualified Border Patrol agents, who work with local law enforcement, is the best way to bolster border security. The number of Border Patrol agents along the U.S.-Mexico border nearly doubled between 2000 and 2017, turning the area into one of the most surveilled and policed parts of the nation.

But recruiting new Border Patrol agents has been a challenge for CBP in recent years. Trump signed an executive order in January 2017 requiring the agency to increase its numbers by 5,000 agents. Despite “aggressive” recruiting, thousands of positions still remain open. In fact, CPB is now losing more agents than it can hire annually, thanks to competition from other Department of Homeland Security agencies, like Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which pays agents more and places them in more desirable locations.

Ironically, with the government shut down over Trump’s border wall beef with Congress, at least 200 Border Patrol agents have been furloughed in the RGV, where Guerra says they are desperately needed. Nationwide, more than 54,000 CBP employees are working without pay.