Observatory Podcast No. 5: Fatal Attraction

Genevieve Keeney discovered her life’s work after a series of untimely deaths.

Transcript:

GENEVIEVE KEENEY: We can’t cheat death. It’s going to come for us. It’s inevitable.

From the Texas Observer, I’m Jen Reel, and you’re listening to Observatory: true stories of life in Texas. Each month, we bring you personal stories told by the people who live in the Lone Star State. Stories about love and murder, addiction and forgiveness. And in this episode, we hear from a 45-year-old woman who’s made her life’s work about death.

***

I met Genevieve Keeney because a Groupon convinced me I should visit a museum about death. “You can’t spell ‘real fun’ without ‘funeral!’” it said. Genevieve works at the museum, which is in Houston, in a plain, one-story brick building with its name in big white letters — The National Museum of Funeral History. To get to the exhibits, you have to walk through a gift shop that has everything from wooden crosses and books about the Arlington National Cemetery to T-shirts and coffee mugs that say “It’s better to be over the hill than under it.” Maybe this was the real fun my Groupon promised me.

But as the name suggests, the museum isn’t about death itself, but about the histories and traditions surrounding it. There’s a behind-the-scenes look at what happens when a Pope dies, a display of fantasy coffins from Ghana, and an exhibit on how people mourned in the 19th century. This exhibit was my favorite. Did you know people used to fashion jewelry out of their dead loved ones’ hair and wear it as a sign of grieving?

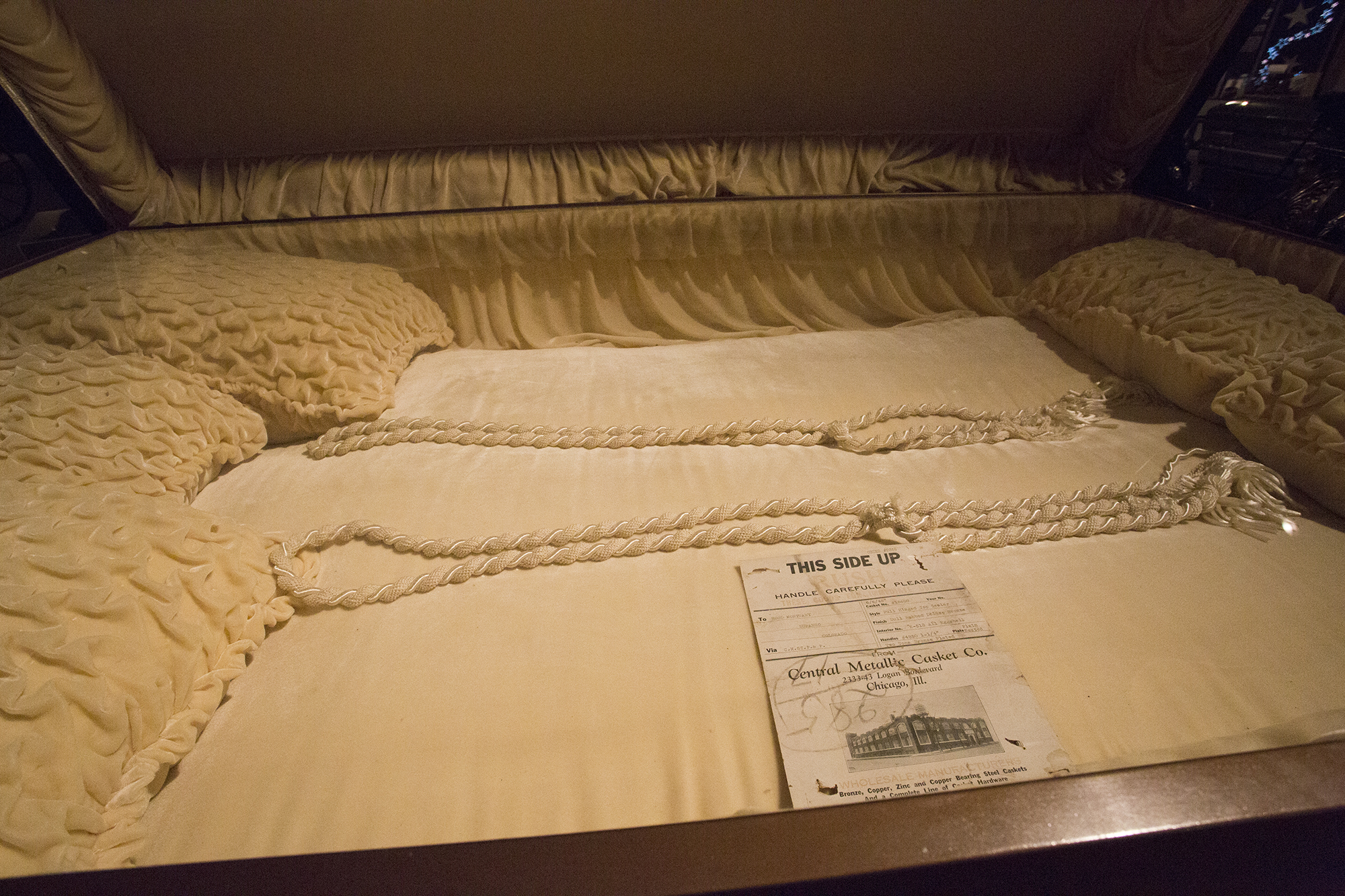

One of the most popular exhibits is a three-person casket from the 1930s. It was custom-built for a couple who felt they couldn’t go on living after their child died, but they never claimed it from the factory in Chicago where it was made. The story goes that the time it took to build this casket gave the parents enough time to work through their grief and eventually abandon their suicide pact.

KEENEY: I really find it to be very symbolic of grief.

That’s Genevieve Keeney, the President of the Museum.

KEENEY: A husband and wife lost their child to death and they were so grief stricken that they wanted to join their child in death. And then it also shows, because we have the casket, that with time grief will lessen. It will get a little easier.

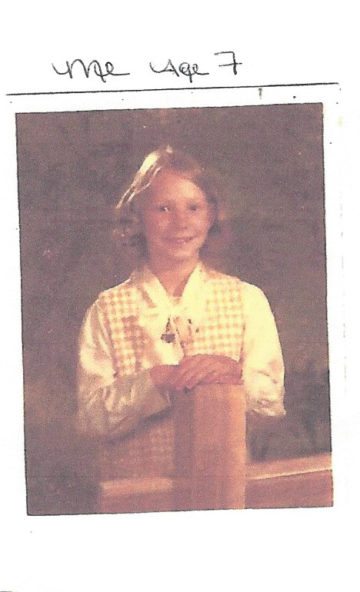

She’s worked here for nine years, but she says her interest in death began when she was just 7 years old.

***

KEENEY: So my younger brother and I would pop-can collect because it was a way for us to be able to get money for candy. And you know, we knew where the college kids lived and we knew that on the weekends on Friday night they’d have parties so there would be beer cans the next morning so we kind of got to know just by walking around where the hot spots were for the cans. And we actually had a competitor in our little area that we lived in. Of course his pop can collecting was more for his living where ours was just a little hobby for candy.

Though one day we decided not to go pop can collecting because we wanted to go play with our friends. I was laying in my bed that night and I could hear the news playing in the other room and over the station came the story about a dead infant that was found in a trash can. And it was found by our competitor, the pop can collector. I remember looking over the bed because my brother was on the bottom bunk and I was on the top and I looked over and said, “That could have been us. That could have been us. We could have found it.” After that, as morbid as it may be, not only was I looking for pop cans now, I was looking to see if I found something dead just so that I could understand it.

While growing up, Genevieve tried to find as much information as she could about death. She says her parents never really talked about it, and she couldn’t Google it — this was before the internet. So she spent a lot of time in the library, and while other kids were preparing school projects on things like cloud formations or the history of the Declaration of Independence, Genevieve used her assignments to talk about death.

KEENEY: I was nervous about speaking, but it transformed into, “Oh my God, are people going to think I’m weird? Who does a cremation presentation in high school and brings their brother?”

He died before I was born, he only lived for 30 minutes. Baby John. There was talk about him but not enough to really put the pieces together and it wasn’t until we moved back to California and I started being very interested about death that my mom told me I had an older brother. My older brother was cremated and he was in a cemetery, never to have been placed in the ground or had a marker because my parents couldn’t afford it. My mom had to go retrieve him. And I told her that I would raise the money to get him out because they had to pay a storage fee. So it was nice to bring him home.

I remember being very careful in carrying him to school with me that day. Had him in the palm of my hand, keeping him safe all the way there. That’s how little he was, you could fit him in a little Q-tip box but it was clear and my whole purpose was to make it clear so people could see. I guess I kind of felt like if I had this curiosity other people may also possess that same curiosity.

***

After high school, Genevieve joined the Army, and was eventually stationed in Schweinfurt, Germany. She worked at a medical clinic that provided health care for the soldiers and their families, and when someone died — which wasn’t all that often, actually — she took care of the bodies.

KEENEY: You know, alcohol poisoning, you know, murder suicides. Over there that’s what takes people. Or childbirths, that unfortunately the child doesn’t make it.

The bodies were then sent for a post-mortem examination to a hospital in Landstuhl, more than 150 miles from the clinic. Genevieve had never witnessed an autopsy. So when the clinic received the bodies of a couple who had died in a murder-suicide, she convinced her commanding officer to let her follow them to Landstuhl.

KEENEY: So now here I am on my first autopsy, and I’m in the room and I’m completely dressed with the face shield and the boot covers and the gown. You know, everything you’ve got to wear, all the protective equipment that you have to put on. And I’m like, “OK, Gen, this is it. You’re here. This is what you’ve been waiting your whole life for.” I guess I was just becoming what I felt was overcome with my emotions. Unbeknownst to me I was standing near the drain where the embalming fluid actually goes, and I guess the fumes of that was making me dizzy. So I left and went in the bathroom. I remember myself being in that bathroom sitting down and putting my head between my knees and saying, “Genevieve, you can not pass out. You need to pull yourself together. This is your moment and get yourself back in that room.”

But after leaving the restroom, Genevieve took one last moment to collect herself in a small waiting room next to the reception area. She could hear humming behind a set of double doors next to the autopsy room.

KEENEY: And this short, older gentleman pops his head out and he’s wearing an apron, and he’s talking to the gentleman at the typewriter. And he looks over at me and he says, “Do you want to come in?” I don’t understand or I don’t know how or why it happened, but when I walked in that room, on that table was an infant. And he was preparing the infant for shipment back to the United States. And he was singing the infant a lullaby. And at that moment I felt like my whole life came full circle. And I said, “This is the infant I’ve been looking for since I was 7.” And I looked up at him and I said, “May I ask what do you do?” And he looked at me and he said, “I’m a funeral director.” And I said, “I want to be a funeral director, this is what I need to be.” And at that moment it was such a, I don’t know. It transformed me from that moment on.

***

Genevieve and her family eventually came back to the United States, where she enrolled at the Commonwealth Institute of Funeral Services in Houston. The museum was on the same campus as the school, and sometimes the museum’s staff would ask the school for volunteers. The CEO of the museum, a guy named Robert Boetticher, was afraid of heights. Genevieve was not. So one of her first volunteer jobs was to help hang new lights. Boetticher was a certified funeral director and had been in the Army, and he and Genevieve bonded over their connections — she even worked for his pet crematory service for a brief period, but when someone showed him a sculpture that Genevieve had done for the Institute, he asked her to interview for a job at the museum.

KEENEY: You have to put together an entire face of a human body. We’re given this plastic skull and a jar of wax and we’re told to make a face, whomever we want. So since Pope John Paul II had just passed away I chose him. I would slowly work on him on my kitchen table and my kids would come down for breakfast or for dinner and they’re like, “Mom, how long is he going to stay on the table? Because he’s becoming more and more real every time we come down.” They’re like, “You’re creeping us out, mom.”

The death of the Pope inspired Mr. Boetticher, too. After seeing the masses who came out for the Pope’s funeral, he wanted to create an exhibit to explain what goes on behind the scenes when it’s time to bury a Pope. Genevieve interviewed and was hired on as museum director, and they began working on the exhibit.

KEENEY: We want to make an exhibit to the Popes, to understand what goes on behind the scenes and it was a 10-by-10 square foot exhibit concept that Mr. Boetticher drew out on a napkin on an airplane and he came back and he showed it to me. Once the approval process went through, wow.

She means approval by the Vatican. THE Vatican. And soon after, their officials began sending Genevieve a ton of information.

KEENEY: It was kind of like we were drinking from the garden hose and we went to immediately the fire hose. It was like, “Whoa, what do we do with all this information?” And, “Wow, we need a bigger building” and “Oh my gosh this is going to be amazing.”

The entire process took three years. The museum added onto their building to fit the new exhibit, and Genevieve minded even the smallest details, like having to convince Customs agents to approve her shipment of ostrich feathers. She needed them in her diorama of the Swiss Guards watching over the Pope lying in state at St. Peter’s Basilica. When the exhibit was finished, Cardinal DiNardo from the archdiocese of Galveston and Houston offered a blessing, and even the Pope’s longtime tailor, Roberto Consorsi, came to tour the exhibit. He rendered his verdict to Genevieve in three words:

KEENEY: Perfecto, perfecto, perfecto. I mean, to me, three perfectos from the Pope’s tailor was validation enough we did a great job.

A lot of people they automatically just think, “Oh, that’s morbid, it’s scary, it’s eerie. Why would I want to see a funeral museum?” But we’re educational, historical, and we actually talk about something that’s going to happen to everybody. It’s about living your life. And knowing that one day you will die, and when you do, what do you want that final party to look like?

Observatory was produced this month by me, Jen Reel, with help from my co-host, Patrick Michels. Anthony Barilla composed our theme and other music in this episode, with additional music by Kevin McLeod. Keep up with us by subscribing to our show on iTunes and Stitcher, and check out our show page at texasobserver.org/observatory. Thanks for listening.