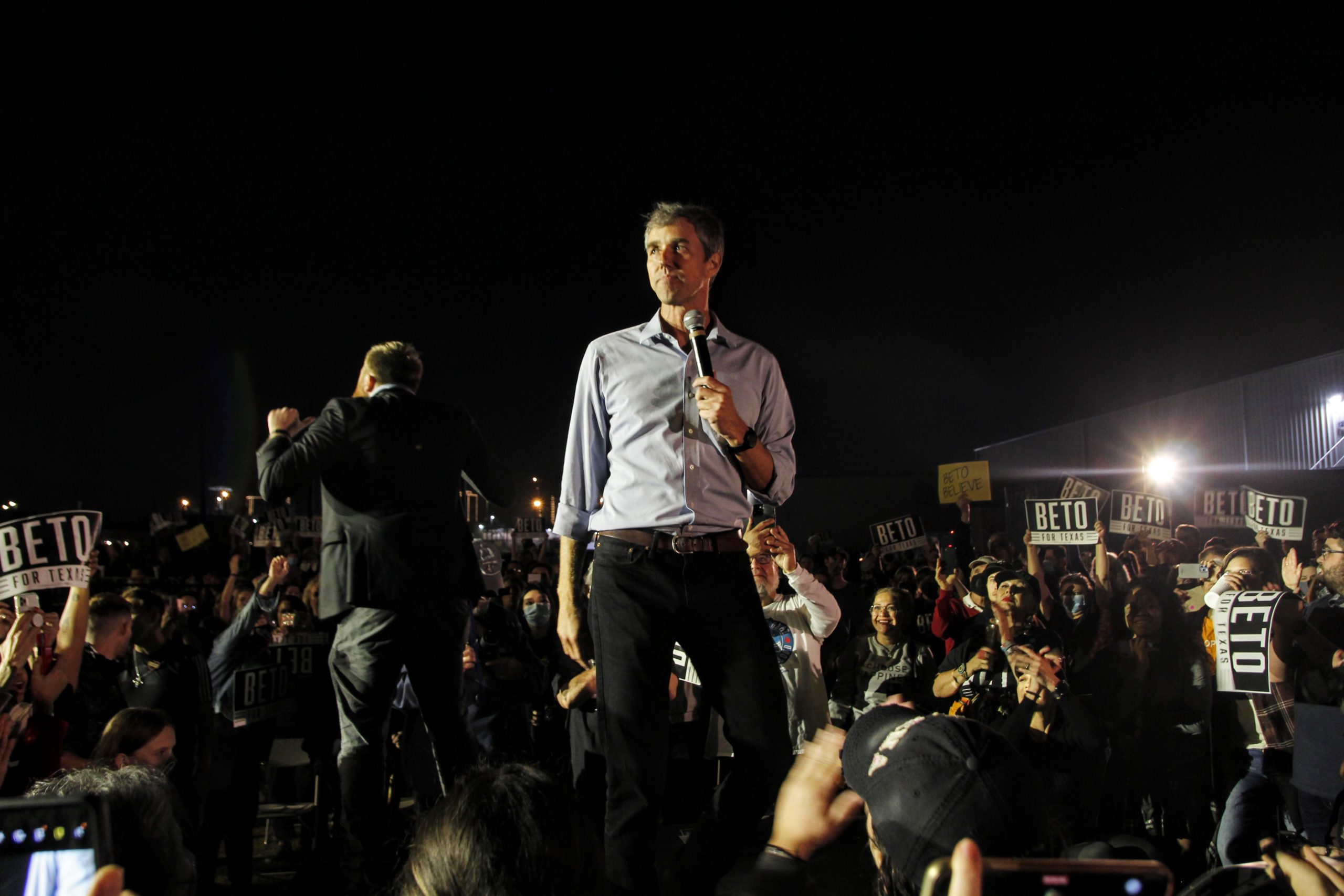

Inconsistent Showing in Democratic Primary Raises Questions for Beto O’Rourke

O’Rourke, the Democrat running the most high-profile statewide race, is scoring only 61 percent in his primary and has room to work in South and West Texas.

Above: Congressman Beto O'Rourke

On primary night in 2014, the candidate who headlined the Democratic ticket, Wendy Davis, got some bad news — her token opponent, Ray Madrigal, scored almost 22 percent of the vote, winning many Hispanic counties in South Texas and the Valley. This, Republicans said, was a protest vote, or evidence of Davis’ softness. Tuesday the same thing is happening — Beto O’Rourke, the candidate running the most high-profile statewide race, is scoring only 61 percent in his primary, against two lesser-known candidates.

Sema Hernandez, challenging O’Rourke from the left, is scoring about 24 percent, taking many counties in South and West Texas. Edward Kimbrough, an even lesser-known candidate, took 15. The spin from the Cruz camp is that this is a humiliation for O’Rourke. The spin from Democrats is that this is a good result, as O’Rourke is the first Senate candidate in some time to avoid a runoff.

O’Rourke’s low number says more about the party than it does O’Rourke, but it’s still not a particularly great sign. A lot of weird things happen in the Democratic Primary, because the party is far from cohesive. A few years ago, a LaRouche acolyte made it into a Senate runoff, and it’s not unheard of for the party’s contender to get crushed in the first round for unclear reasons. The fact that Hernandez and Madrigal won in many of the same places seems to point to the benefit of running with a Hispanic last name in the Democratic Primary. It’s possible voters really took to Hernandez’s and Kimbrough’s message, of course, but it seems likely more evidence that lots of Democrats enter the primary booth with limited knowledge of who is on the ballot and select names — ask Grady Yarbrough and Jim Hogan. And it’s hard to blame them, because the “frontrunners” that usually are on the ballot aren’t exactly titans.

That said, O’Rourke’s soft spot so far has been name recognition. If you’ve seen 30 news stories a day about O’Rourke for the last six months and seen some of his packed rallies, that might seem strange, but there’s room to question whether all the hype about the “punk rock Democrat” is translating to the masses — one poll in January reported that 93 percent of Texas voters have an opinion about Ted Cruz, while only 39 percent had one of O’Rourke. In places where his name recognition is likely highest, O’Rourke did well — 90 percent in El Paso, his home county, and 87 percent in progressive Austin. But in Dallas and Harris, the party’s redoubts, he won only 58 percent, and in Bexar, only 63.

Those are places where O’Rourke will need, in November, to step outside his most enthusiastic supporter groups of white and young progressives and mobilize a lot of other people. Or the party can do it for him, or hatred of Trump can. No need for alarm bells yet, but tonight’s result provides another opportunity for O’Rourke to take stock of whether his DIY campaign is doing what needs to be done.