COVID-19 Has Delayed Programs That Texas Prisoners Need to Get Out

People approved for parole in the Texas prison system already waited months to start programs required for their release. Coronavirus is making some wait even longer.

A version of this story ran in the July / August 2020 issue.

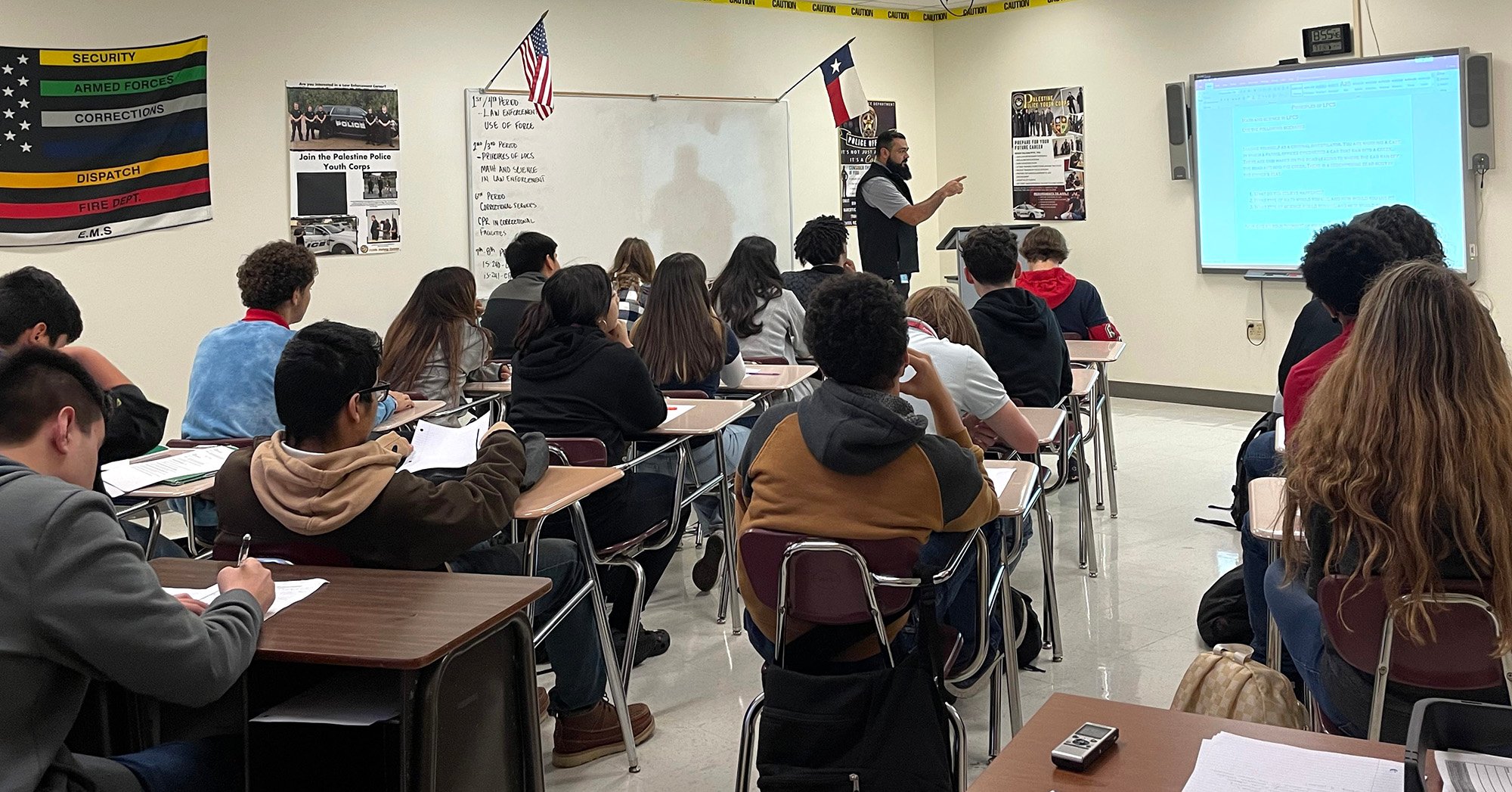

Above: In late May, people with loved ones behind bars who were eligible or already approved for parole rallied outside the governor’s mansion near the Texas Capitol

Darcy Vargas says it felt like an early Christmas present when her son Gerald made parole in early December after serving more than a year in the Texas prison system for a drug charge. Once he completed a six month rehabilitation program, a requirement for his release that was set by the state parole board, Gerald would get to go home. “We were so excited thinking he’d be out by summer,” Vargas told me. “We’ve got a job waiting for him and everything.”

But that excitement eventually turned to frustration. While the parole board approved Gerald’s release in December, prison officials said he couldn’t start his required rehab program until February of 2020 at the earliest. In March, he was approved to be transferred to another facility where he could begin the six-month release process, but then COVID-19 hit, upending Texas prisons and halting both visitations and most inmate transfers. The Sanchez State jail in El Paso, where Gerald is currently housed, has been on lockdown for more than a month after inmates and staff tested positive for the virus. Then, in late April, officials told Vargas that her son would have to wait to start his program.

“He sounds so frustrated and that makes me so worried,” Darcy told me. “That’s a tough place to be anyway, but now they’ve been on lockdown for so long that tempers are starting to rise.”

Gerald Vargas isn’t alone. At least 10,500 people incarcerated by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) have been approved for release by the Texas parole board but remain in prison while they wait to finish required pre-release programs. For months, advocates for incarcerated people and their families have urged state officials to allow inmates already approved for release to finish those programs at home as a way to reduce the prison population, which experts have said is the best way to lower the risk for COVID-19 for prisoners, staff, and the communities to which they’ll return.

As of this week, about 6,900 people incarcerated by TDCJ and more than 1,000 prison employees have tested positive for COVID-19. At least 42 inmates and 7 prison staff have died from the virus, but even as those numbers rise, Governor Greg Abbott—and the parole board he appointed—has largely ignored calls to release people who have already made parole.

“It’s outrageous that people who are approved for parole cannot not be released,” said Jennifer Erschabek, executive director of the Texas Inmate Families Association. “It hurts Texas citizens because they have to shoulder the financial costs of inefficient management of the prison population.” Those costs are significant—$62 per person per day for more than 10,000 people. “It hurts the families involved who worry about losing a family member to COVID-19 because they can’t get their family member home,” she said.

TDCJ officials have denied any delays or interruptions in pre-release programs due to the pandemic. However some people midway through completing those programs have told me their classes have been replaced with correspondence work that they now complete on their own in their cells—work that advocates insist could be completed outside of prison.

“If we’re giving people paper packets for drug rehabilitation, they could just do that at home,” said Lauren Johnson, a criminal justice outreach coordinator with the American Civil Liberties Union of Texas, who was herself formerly incarcerated. “If we think paper packets are going to solve their addiction issues, then I’m sure there’s a better place to do that than prison.”

In late May, people with loved ones behind bars who were eligible or already approved for parole rallied outside the governor’s mansion near the Texas Capitol. Olga Estrada, who drove five hours from her home in the Rio Grande Valley to join dozens of other families, carried a sign with photographs of her husband, Danny Flores, who made parole in March but has yet to start the classes that are required for his release. For more than a month, Flores has been on lockdown at the Wayne Scott Unit in Brazoria County, where at least one inmate has died from COVID-19. Estrada says she had almost no contact with him until two weeks ago, when he started getting occasional five-minute phone calls home. She says the extended separation has been particularly difficult for their children. “My youngest daughter, she cries every day for her daddy now,” Estrada said.

Others fear for their loved ones remaining in prison longer than the parole board has even deemed necessary as the pandemic continues. Holly Hein Parker was elated when her husband, Bob, made parole in March after nearly a year and a half in prison for drug charges. Bob used to call her several times a day until April, when the Terrell Unit, where he’s incarcerated, went on lockdown. Three people incarcerated there have since died from COVID-19.

Holly, who’s an artist, says she went weeks without communicating with her husband. Around his birthday, in early May, Holly started channeling her anxiety through a series of paintings that are notably darker and more somber than her previous work. “They are a collection of fear, dreams, nightmares—imagery that seems to flood my head these days,” she told me.

Bob finally got his first five-minute phone call with Holly on Memorial Day. It was the first time they’d spoken since the Terrell Unit went on lockdown in April. While he’d previously been scheduled to begin a six-month pre-release rehab class in June, Holly says they now have no idea when that might start. “The call was tearful, happy but bittersweet because there’s only so much you can cram into five minutes,” she said. “I’m just thrilled to be able to hear his voice.”

Read more from the Observer:

-

The Protests Against Police Brutality in Texas, in Photos: Demonstrations against police brutality are taking place in cities large and small across Texas.

-

‘Heroes’ No More: Grocers Are Already Clawing Back COVID-19 Worker Benefits: Kroger revoked its “Hero Pay” in May, while public health experts warn of COVID-19 surges as Texas reopens.

-

Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins on Battling COVID-19, and the Governor, as Texas Reopens: “Now we’re just working with this unprecedented state usurpation of local control, trying to keep people safe as best we can.”