Fire and Innocence

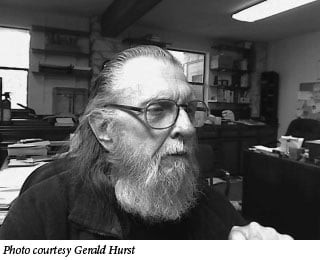

Gerald Hurst is one of the nation’s foremost authorities on fire and explosives. At age 72, he’s tall and lean, with graying hair combed back on his head and a white beard—think Santa Claus after a Nutrisystem diet. Within minutes of welcoming me into his West Austin home in the fall of 2008, he had me hooked, recounting vivid, head-scratching stories of person after person who’d been wrongly convicted of arson.

That was what I’d come to hear. I had developed a fascination with arson cases—specifically, with the methods fire investigators used to distinguish intentionally set fires from accidental ones. Until recently, the process was more art than science. And in many places, it still is. Fire investigators long worked from a basic set of assumptions about how buildings burn—”old wives’ tales,” as Hurst calls them, passed from one generation to another. For decades, they walked into the remains of charred buildings in search of the same clues to arson: furniture and windows buckled by extreme heat; burn patterns on the floor caused by an accelerant like gasoline; and other markers that were supposed to indicate that a fire had spread, quickly and wildly. They took those markers to mean that a fire had been ignited on purpose. And then they used the evidence to send thousands of people to prison.

But many of the investigators’ assumptions have turned out to be wrong. Over the past 15 years, the forensic science of arson has undergone a revolution led by experts like Hurst. With nearly 800 people serving time for arson convictions in Texas prisons alone, the wider implications aren’t hard to grasp. It now appears that hundreds of Texans have been wrongly convicted on the basis of outdated and inaccurate forensic evidence. Nobody knows exactly how many, because no one’s looked comprehensively at the cases of those in prison for arson. I wanted to dig into as many of those cases as I could. Hurst liked the idea, and he offered to help examine any suspicious cases I could turn up through court documents and police records.

Hurst, who holds a doctorate in chemistry from Cambridge University, spent most of three decades working in the private sector as a fire and explosives expert. He also worked as an expert for hire in civil cases, usually insurance disputes over the cause of a fire. His first exposure to the shoddy forensic science being used as evidence in criminal cases came only about a decade ago. Hurst was asked to examine the evidence used to convict a Fort Stockton woman named Sonia Cacy, sent to prison in 1993 for allegedly killing her uncle in a house fire. Hurst and his wife drove to West Texas to meet Cacy. On the way, Hurst read through her case file. He was shocked to see the flawed, outdated forensics that had been used in this capital murder case. Cacy was innocent, and Hurst’s testimony ultimately helped exonerate her. She was released in 1998 after serving six years of a 99-year sentence. It also gave him a new mission. Since the late 1990s, Hurst has testified, pro bono, in dozens of arson cases around the country as an expert witness for the defense. In Texas, he helped exonerate Ernest Ray Willis, who spent 17 years on Death Row for a fire he didn’t start.

But Hurst has gained the most notoriety for his work on the now-infamous Cameron Todd Willingham case. Willingham was convicted of arson murder for allegedly starting a 1991 fire at his North Texas home that killed his three daughters. Just weeks before Willingham’s execution in 2004, Hurst was asked to look at the evidence. He saw immediately that investigators had used outdated assumptions to convict Willingham. Working against the clock, he hurriedly wrote a report that debunked much of the physical evidence. Hurst concluded in his report that “most of the conclusions reached by the Fire Marshal would be considered invalid in light of current knowledge.” (You can read the whole report here.) Willingham’s lawyer faxed the report to Gov. Rick Perry’s office hours before the scheduled lethal injection. Because the governor’s office has refused to release relevant documents, it’s unclear what, if anything, the governor’s staff did with Hurst’s report or whether Perry ever saw it. But the governor let the execution go forward.

Hurst was the first fire-science expert to review the case. Since Willingham was put to death, eight more of the nation’s leading fire scientists have examined the evidence. Every one of them has agreed with Hurst that the forensics were outdated and that the fire was likely accidental. That would mean Texas almost certainly executed an innocent man.

In the past few months, the Willingham case has become a full-blown scandal. The New Yorker ran a 16,000-word story in late August, and all of a sudden people across the country were talking about the case. Then in late September, Perry booted three members off of the Texas Forensic Science Commission, which was investigating the Willingham and Willis cases, just three days before a crucial hearing on scientists’ findings. Perry’s new appointees promptly canceled the hearing and have yet to reschedule it. Even conservative commentators cried cover-up, suggesting that Perry, in a tough battle for re-election, was trying to subvert an investigation that might prove he oversaw the execution of an innocent man.

The Willis and Willingham cases are not unique; they just happen to have gained wide public attention. Hurst has seen many cases in which the forensic evidence was as bad or worse. In the basement of his Austin home, he continues to dig through case files submitted by attorneys and families across Texas and the nation. In the last two weeks of October alone, he received requests to examine a half-dozen arson cases. Some of the defendants are obviously guilty, he says. Other cases have flaws that leave questions about the defendants’ guilt. But in about half the cases he sees, fire investigators have conjured arson evidence that is so obviously wrong—based on ludicrous theories and long-disproved methodologies—that it would almost be funny, he says, if someone weren’t sitting in jail because of it.

The Willis and Willingham cases are not unique; they just happen to have gained wide public attention. Hurst has seen many cases in which the forensic evidence was as bad or worse. In the basement of his Austin home, he continues to dig through case files submitted by attorneys and families across Texas and the nation. In the last two weeks of October alone, he received requests to examine a half-dozen arson cases. Some of the defendants are obviously guilty, he says. Other cases have flaws that leave questions about the defendants’ guilt. But in about half the cases he sees, fire investigators have conjured arson evidence that is so obviously wrong—based on ludicrous theories and long-disproved methodologies—that it would almost be funny, he says, if someone weren’t sitting in jail because of it.

“Older cases, you can pretty much assume it’s probably a bad case,” Hurst says. “But new cases come in too, and only a small percentage of them are really good cases—I mean where they’ve done their homework, eliminated accidental causes and pretty well established arson. But I don’t see many. I see [investigators] doing some of the same things they were doing in the ’80s.”

With Hurst’s help, I soon identified three Texas men who were convicted largely by disproved arson forensics. The Observer has told their stories this year as part of a series that will continue into 2010. (See below for a review of the three cases we have documented thus far.) The evidence against Curtis Severns of Plano, Ed Graf from outside Waco and Alfredo Guardiola of Houston was thin and occasionally absurd. Yet their cases, unlike Willingham’s, received little or no media attention. All three are almost surely innocent. All three remain in prison on sentences that stretch for decades to come. And they are far from alone.

Texas fire statistics suggest that those falsely convicted of arson number in the hundreds. Hurst’s research leads him to contend that at least one-third, and perhaps even half, of all arson convictions have been based on junk science. In Texas, that would mean between 250 and 400 likely innocent people are sitting in prison at this very moment.

“So,” Hurst asks, “what do you do about it?” For Texans concerned about this mass miscarriage of justice, that is now the urgent question.

The first step in remedying the widespread problem of false arson convictions is understanding why they happen.

Arson is one of the rare crimes for which a defendant can be convicted almost exclusively on the basis of a forensic expert’s testimony. If a fire investigator testifies that the blaze at your house or business was intentionally set, someone—quite possibly you—is headed to prison. It can happen to anybody. The three stories documented thus far by the Observer demonstrate that.

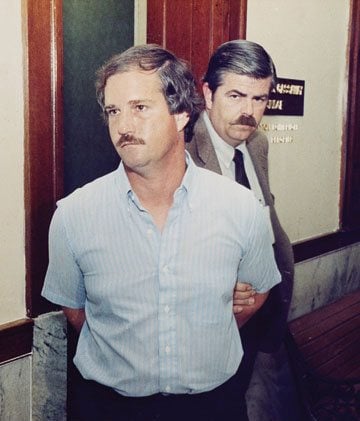

Curtis Severns (“Burn Patterns,” April 3) was a gun store owner, husband and father in a Dallas suburb. After many fits and starts, he finally saw his life coming together—until the night his store burned in 2004. Severns had been the last to leave the store before it exploded in flames. He maintained his innocence, and there was no valid evidence that the store had been intentionally torched. But expert testimony convinced the jury that Severns did it. He landed in federal prison on a 27-year sentence he is still serving.

Curtis Severns

Curtis Severns

The Fire: In his Plano gun shop on Aug. 21, 2004.

The Evidence: Prosecutors claimed multiple points of origin at scene proves Severns committed arson. Accidental fires almost never start in multiple places.

Forensic Flaws: Fire scientists say it was likely started by an electrical short and spread by exploding aerosol cans full of flammable gun cleaner. New video evidence proves aerosol cans can spread fire and create the illusion of multiple points of origin.

Motive: He drastically reduced his insurance policy months before the fire. He would have lost money if the store were destroyed.

Sentenced to: 27 years in federal prison in June 2007.

Postscript: Severns remains in federal prison in Beaumont. His sentence has been reduced; he has 15 more years to serve. After the Observer story, Walter Reaves, a Waco attorney who works with the Innocence Project of Texas, took on the case pro bono.

Ed Graf (“Victim of Circumstance,” May 29) had built a life that many would envy. He was an insurance adjuster with a healthy salary, a family and a large house in an affluent suburban neighborhood outside Waco. His alleged crime was so horrific—Graf was convicted of dragging his two young stepsons to a backyard utility shed and burning them alive—that many in the Waco area still remember it vividly, two decades into Graf’s life sentence for arson-murder.

Ed Graf

The Fire: In a shed behind Graf’s house in suburban Waco on Aug. 26, 1986, that killed his two stepsons.

The Evidence: Fire investigators contended that burn patterns at the scene and the position of door locks proved Graf had ignited gasoline and locked the door to the shed.

The Forensic Flaws: Nearly every piece of forensic evidence that convicted Graf has since been disproved. Reading burn patterns in post-flashover fires is no longer seen as a reliable way to determine how a fire started. Subsequent investigation also showed that the door to shed was likely open. If the door had been closed, the fire would have burned out from lack of oxygen in a windowless shed. Defense attorneys theorized the kids, who had history of playing with fire, might have started the blaze and lost control.

Sentenced to: Life in prison in 1988.

Postscript: Little has changed in Graf’s case since the Observer’s original story. Graf remains in state prison.

Alfredo Guardiola (“I Was Just a Junkie,” Oct. 2) was a heroin addict living a semi-nomadic existence in a poor East Houston neighborhood. He’s now served half of a 40-year sentence for allegedly starting a house fire that killed a married couple and two children Guardiola had never met. He was connected to the fire only because he rushed from a neighbor’s house to try to help the victims.

Alfredo Guardiola

The Fire: In a house in East Houston that killed two adults and two children on May 11, 1989.

Evidence: Guardiola confessed to the crime after 13-hour interrogation. He quickly recanted and says the confession was coerced. Fire investigators also believed burn patterns at the scene proved an arsonist used gasoline to start the fire.

Forensic Flaws: Experts see no evidence of arson. No gasoline was ever detected at the scene. Fire scientists say the burn patterns were likely caused by flashover, not gasoline. Testimony from numerous eyewitnesses points to an accidental fire.

Motive: Prosecutors contended Guardiola burned the house to prevent the family from implicating him in recent burglaries. But Guardiola wasn’t directly involved in the burglaries, and the family didn’t even know who he was.

Sentenced to: 40 years in prison in 1993.

Postscript: Guardiola has 20 years left on his sentence. After reading the Observer story, lawyers with the Innocence Project of Texas are looking into Guardiola’s case.

As different as each case is, all three have something in common: They were based on arson evidence that’s been long since disproved. For instance, all three fires appeared to spread unusually fast and burn unusually hot. That was once considered a sure sign that an accelerant like gasoline had been used to ignite a blaze. And where there was gasoline, the theory went, there had to be an arsonist.

Research has shown that the theory is bogus. Accidental fires can burn even hotter than blazes set on purpose. At www.texasobserver.org, you can watch a video of a test fire in which a lit cigarette left in a couch turns a room into an inferno in just four minutes.

The first time I spoke with Gerald Hurst, we sat on the wraparound sofa in his living room. He pointed out that if the couch we were sitting on—given its size and flammable material—happened to ignite, it would engulf the room in just minutes.

Many investigators still look for clues that a fire has burned especially hot—melted bed springs, deeply charred wood. Scientists now know that these can be products of an accidental fire. But they have long been used as evidence of arson.

One of the most infamous falsehoods is the phenomenon of “crazed glass,” in which weblike cracks form on a window of a burned building. Crazed glass was once considered proof that a fire had burned especially hot and fast, and thus had to be arson. This notion was used to convict Cameron Todd Willingham. But recent experiments have shown that crazed glass actually occurs when water from a fire hose hits a hot window.

Another longtime staple of fire investigation is “reading” the burn patterns at a scene. Investigators believed that certain types of burns on a wall or floor could tell the story about how a fire ignited, and that story often involved gasoline. In trials, investigators have testified that they observed “pour patterns” on a floor, where the defendant had supposedly poured gasoline. They’ve also cited burn marks on walls that they said meant the fires had started on the floor, fueled by gasoline, and quickly burned upward.

Those myths of arson science were proven false in 1991, when fire investigators in Jacksonville, Fla., made a startling discovery. They were probing a house fire that looked like textbook arson: “Pour patterns” could be seen on the floor after a fire that had spread rapidly. Gasoline must have been used, the investigators thought. But to be certain, they took the unusual step of running a test that would become known as the Lime Street Fire. The investigators found an abandoned house nearby, similar to the one that had burned, and filled it with similar furniture. Then they staged an accidental fire scenario—no gasoline used, in other words. When the test fire was extinguished, the investigators were stunned to see similar “pour patterns” scorched on the floor. How could that be, if no gasoline was used?

Eventually they figured it out. The original house fire had achieved a level of intense burning known as “flashover,” which occurs when enough smoke and gas intensify to make a room explode into flames. (The telltale sign of flashover is when flames burst from windows and curl toward the roof.) At flashover, a fire can spread quickly in many directions—even downward, which investigators once thought was impossible. Flashover caused by accidental fires can leave burn patterns and create burn holes in the floor that were previously thought to prove that an arsonist had ignited several starting points. “Pour patterns,” it turned out, were actually burn marks left by post-flashover burning. They were not signs of arson. In essence, the Lime Street Fire showed that flashover can make an accidental fire look very much like an arson.

The fires that led to both Graf’s and Guardiola’s convictions went to flashover. Investigators testified that “pour patterns” and other burn marks convinced them that gasoline—and, thus, arsonists—had started the fires. Hurst is convinced that the burn patterns were caused by normal post-flashover burning. (In Guardiola’s case, no evidence of gasoline was even found.)

“There is no such thing as a pour pattern after you’ve had prolonged post-flashover burning,” Hurst says. After flashover, it’s very difficult—often impossible—to determine how a fire started.

But even today, Hurst still sees cases in which investigators base arson findings on burn patterns caused by flashover. “How long has it been since I’ve seen a case like that?” he asks rhetorically. “Oh, I haven’t seen a case like that since, I think it’s been, two weeks.”

In many parts of the country, and in much of rural Texas, fire investigators are poorly versed in the forensic discoveries of the last two decades. Most are former firefighters or police and military officers. In many jurisdictions, they can become certified fire investigators after a 40-hour course.

John Lentini, who helped run the Lime Street experiment in Florida and later examined the Cameron Todd Willingham case, says the problems with arson evidence won’t be fixed until fire investigators have a better understanding of science. “As long as we want to pay $35,000 a year to an ex-firefighter,” he says, “we’re not going to be able to afford the kind of people who need to be doing the work.”

In a perfect world, Lentini would like to see departments pay fire investigators more and require an advanced degree in physics or chemistry. He knows that’s unlikely. The more immediate and affordable solution is better training: Make the courses longer and more intensive, so “guys who are truly incompetent won’t get certified.”

Training for investigators has improved in recent years, and fire investigations are much more scientific than they once were. But it’s scattershot, says Gerald Hurst. “It’s totally non-uniform. There are pockets where they get it right, because they’ve taken the right courses.” At the same time, Hurst says, “There are literally thousands of fire investigators doing whatever they damn well please. There are courts who don’t have a clue what’s real and what’s not, and their sources of information … are the very people who are doing the bad investigating.”

Hurst suspects that some investigators learn proper techniques during their initial training but are subsequently influenced by apprenticeships with older investigators who still subscribe to those “old wives’ tales.”

To remedy the problems with fire investigation, Hurst and Lentini both want to see a standardized curriculum instituted by state fire marshal offices. They also believe that investigators, to maintain their certifications, should be required to take annual continuing education courses.

Beyond better training and certification, Lentini and Hurst also recommend changing the way arson cases are tried. Arson trials are different from those of other crimes because the basic issue normally isn’t who committed the crime but whether there was a crime at all. “If it’s arson, it’s usually pretty obvious who did it,” Lentini points out. But if the fire was accidental, no crime occurred in the first place.

One solution: separate trials into two segments. In the first phase, the defendant would not even be in court. The exclusive issue would be fire science: Was this arson? If a jury concludes that the fire was intentionally set, the second phase of the trial would begin, with the defendant’s guilt or innocence determined.

This reform would change the outcomes of many arson trials. Prosecutors often center their cases on demonizing defendants—a handy way to mask flaws in arson evidence. This technique was used in all three cases investigated by the Observer. Curtis Severns, the gun-shop owner, was misleadingly portrayed at his trial as broke and desperate for the insurance money the blaze would bring. Ed Graf was described in court as a monstrous “Jekyll and Hyde” type. Alfredo Guardiola was depicted as a gangster. Cameron Todd Willingham is still being called a “monster”; Perry said so in October when he declared that, even if the arson evidence was mistaken, Willingham was still guilty because he was an awful person. And perhaps the most egregious example was Ernest Ray Willis, who was administered powerful sedatives during his 1987 trial in Fort Stockton. In open court, the prosecutor referred to the drugged-up Willis’ eyes as “cold fish eyes.”

How many innocent people have been convicted of arson in Texas? Data from the state fire marshal’s office offer chilling clues that point to a number in the hundreds.

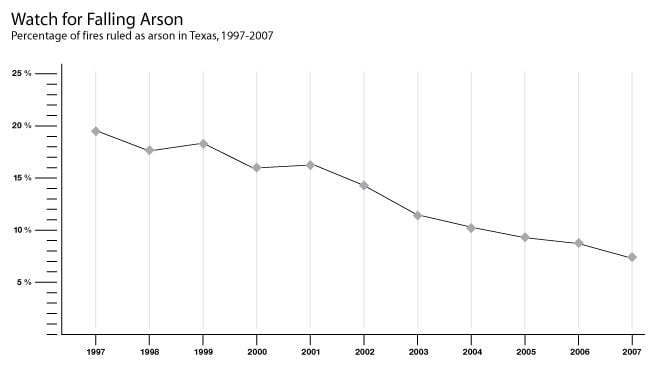

As the new understanding of how fire behaves has slowly penetrated the world of fire investigation, the number of fires considered arson has dropped dramatically in the state. Between 1997 and 2007, there was a 60 percent drop in the number of fires deemed “incendiary.” In 1997, 15,949 arsons were reported in Texas. Ten years later, the number had fallen to 5,687.

But there aren’t fewer fires in Texas. The overall number of fires remained fairly consistent in that 10-year period, from year to year, between 73,000 and 95,000.

Are there simply fewer arsonists? Gerald Hurst doesn’t buy that. Rather, it seems clear to him that fire investigators are getting it right more often. He believes that improved and standardized training would lead to another huge decrease in the number of arson findings.

The massive drop in arsons points to disturbing evidence of how many potentially innocent Texans might be in jail. If most of the 60 percent drop is accounted for by accidental fires that would have been ruled arsons in previous years, it’s reasonable to assume that 30 to 50 percent of the people in prison on arson convictions are innocent.

In Texas, that would add up to between 250 and 400 wrongly convicted people.

Even so, no one has attempted a comprehensive review of older arson cases. To date, the job of examining those convictions has fallen on media outlets like the Observer and nonprofit groups like the Innocence Project, which lack the resources for a comprehensive review of all cases. Criminal-justice experts like Scott Henson, who writes the Grits for Breakfast blog, have called on the Texas attorney general’s office to conduct a statewide probe of arson convictions. It’s difficult work that requires significant funding.

The Texas Forensic Science Commission could make a huge dent in the problem. The Legislature created the commission in 2005 after scandals at crime labs around the state. The commission was charged with investigating innocence claims based on flawed forensics and bringing to light faulty practices that might have sent innocent people to prison. It’s one of the first such governmental bodies in the country. For once, it looked as if Texas would be a criminal justice innovator.

But Perry’s intervention has halted any progress by the commission. John Bradley, the hard-nosed Williamson County prosecutor Perry recently put in charge of the commission, seems intent on writing new rules and procedures. Critics view this as a stall tactic. At a recent legislative hearing Bradley refused to say when he planned to restart the investigation into Cameron Todd Willingham’s conviction and execution.

It’s still possible that the commission’s final report on the Willingham case will provide a primer of sorts for arson investigations, an official list of the types of fire evidence that should not be admitted in court. But with Bradley delaying the probe, it could take years for the commission to issue findings. Asked by lawmakers when the commission might report on the Willingham case, Bradley replied, “When it’s ready.”

Meanwhile, Severns, Graf and Guardiola remain in prison. Following the Observer’s exposés, their cases have received some media attention through newspaper stories, radio reports and blogs. The Innocence Project is working to free all three men. But the criminal justice process is grindingly slow. And hundreds of other innocent people are almost certainly wasting away in Texas prisons.