In This Budget, No Good Options

If you want to understand the consequences of balancing Texas’ budget without raising taxes, just listen to Anne Heiligenstein. She provided the best description I’ve heard yet of the twisted math at work in the Capitol.

Heiligenstein heads the Department of Family and Protective Services, which runs the state’s foster care system and Adult Protective Services, among other programs. She appeared on Tuesday morning before the Senate Finance Committee to describe how her department planned to deal with a massive drop in funding.

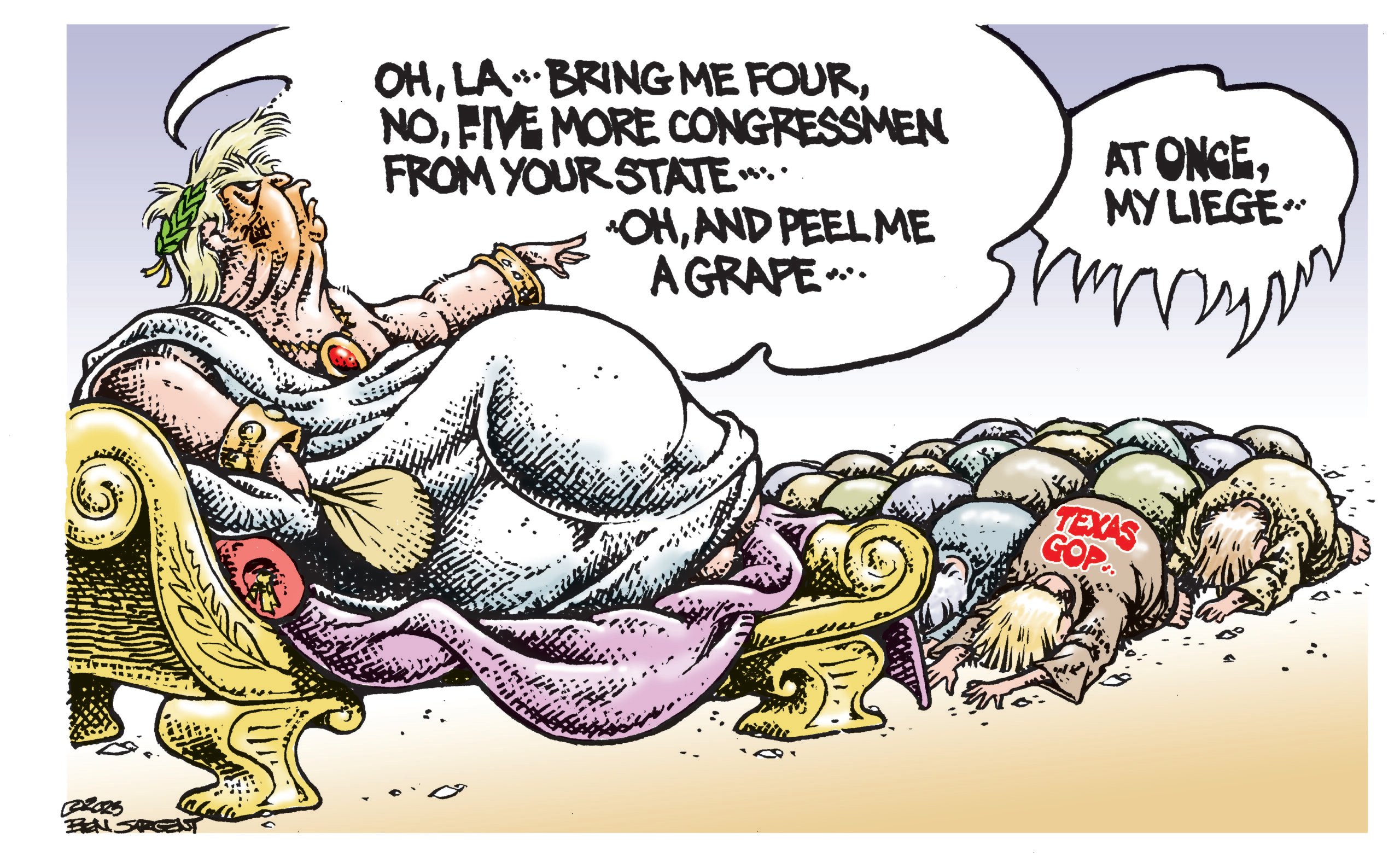

Republicans in the Legislature are trying to close a $27 billion budget hole without raising taxes. State leaders such as Gov. Rick Perry and Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst have assured us the budget can be balanced without harming “essential” services.

It falls to the budget-writing committees to figure out what constitutes “essential.” We can’t pay for all the state’s current services—not without raising taxes. And Texas already spends less per resident than nearly every other state. So almost all our spending could already be considered essential.

The question hanging over the committee hearings the past two days was: Who’s most essential? Who’s most desperate for help—the abused children or the nursing home residents or the emotionally disturbed kids who might need help soon or the mentally ill? How do you decide whose program takes precedence?

It’s a sick game to play, but these are the questions lawmakers will have to consider.

As Heiligenstein noted, the initial Senate budget plan would result in a 12 percent cut in the amount of money her agency pays residential treatment centers to care for foster kids. The pay cut could cause some treatment centers to refuse to work with the state because they’d lose too much money on the deal. As it stands now, the state pays treatment centers only about 80 percent of the cost of caring for foster kids. If that rate drops 12 percent, and the state can’t find treatment centers to take kids, we’ll probably end up with hundreds of foster children sleeping in state offices. (This actually happened in 2007, when 611 kids stayed in state offices—a disturbing outcome that lawmakers rectified with increased funding. This year only 12 kids slept on sofas.)

Heiligenstein is begging the Legislature not to force her to undo that progress. Preventing a 12 percent provider rate reduction was one of Heiligenstein’s top budget requests.

But it’s not the only program facing cuts, of course. She then observed that the draft budget would force a 40 percent cut to prevention programs that help keep kids out of foster care. The state’s successful kinship care program—which helps abused children stay with relatives like grandparents, and aunts and uncles so they don’t end up with a foster family—would be zeroed out. The prevention programs not only lead to better results for kids, but by keeping children out of foster care, they save the state money in the long run.

Some of the senators grilled Heiligenstein on why she wasn’t prioritizing prevention programs. In her answer, she hit on the ludicrous choices she faces.

“I have this house on fire over here,” she said, referring to proposed foster care cuts that might lead to kids sleeping on sofas in state offices. She then termed cuts to prevention programs “a house with bad wiring that might be on fire in a couple of years…..I made the decision to deal with the house that’s on fire right now.”

And there you have it—the 2011 budget process in summary: Burn down your house now or burn it down in a couple of years. The budget process comes down to deciding which outcome is less bad. .

That was just one agency. A few hours later, officials from the Department of Aging and Disability Services made their case. They said the draft Senate budget would lead to a 33 percent cut in Medicaid payments to nursing homes.

Keep in mind that at least 70 percent of residents in 550 Texas nursing homes are on Medicaid. We’re talking a lot of seniors. How, Sen. John Whitmire (D-Houston) asked, can nursing homes reduce costs that much? There’s no magic answer, the bureaucrats said. Nursing homes would have to serve less food, hire fewer nurses, check the patients less often. “I think a 33 percent reduction in nursing home rates isn’t practical,” concluded Tom Suehs, who oversees all health and human service agencies in Texas.

Of course, if the state fully funds Medicaid rates for nursing homes, that takes money from another vital area. There are many other programs facing cuts that aren’t “practical.” Budget writers are proposing closing a state hospital for the mentally ill. And community mental health centers, which provide outpatient treatment and already have a huge waiting list, are facing a 40 percent cut in funding.

So, who’s less essential? The abused kids, the nursing home residents, the mentally ill, the Medicaid recipients? After just two days of hearings, it’s already clear that legislators either must tap the Rainy Day Fund and raise more revenue—or they will have to employ some twisted logic to decide whose program gets cut. There will be no good options, only less bad ones.