Dow’s Reservoir and the Realities of Flooding in Texas

The petrochemical giant's impact studies fail to address serious concerns about their proposed Harris Reservoir Expansion along the Brazos.

Editor’s note: This is part of Drifting Toward Disaster, a Texas Observer series about life-changing challenges facing Texans and their rivers.

The Texas coast regularly experiences major storms and flood events with devastating consequences to those of us who live and work in their paths. As each storm passed in recent decades—Allison, Rita, Ike, Harvey, and more—hard lessons were learned and improvements initiated. Future storms are inevitable. With appropriate planning, we can minimize future flooding impacts while still improving our overall economy and quality of life.

Unfortunately, some Texans instead continue to ignore foreseeable flood impacts and create avoidable future destruction.

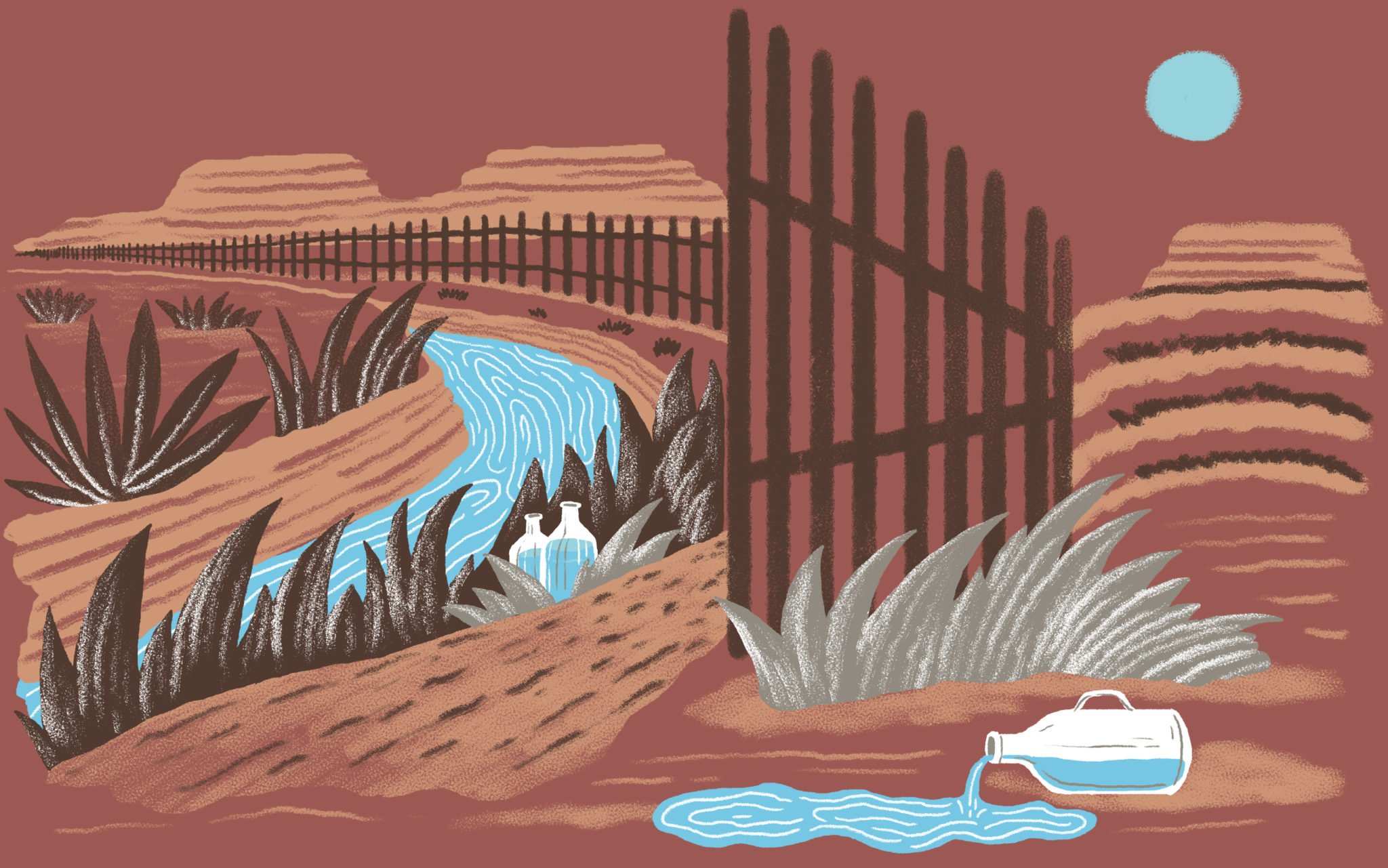

Dow Chemical’s proposed Harris Reservoir Expansion is a prime example of such poor planning. This project would surround about 2,000 acres in the current Brazos River/Oyster Creek floodplain, just north of the current Harris Reservoir, with 40-foot tall embankments. The project would be located in Brazoria County, between the Brazos River channel and Oyster Creek, and would block current floodwater overflow and storage areas.

Flooding in this area primarily occurs when upstream rainfall flows down the Brazos River into the broad coastal floodplain, an area south of Houston and Sugarland and north of West Columbia, Lake Jackson, and Freeport. With this new reservoir in place, where would floodwaters blocked by this project go? What areas might experience new or increased flooding?

The studies submitted by Dow model rain falling directly on its new off-channel reservoir instead of answering these more relevant questions.

My education as an engineer and my personal experience confirms that proper planning and flood mitigation can help minimize damage to homeowners. My home in Houston flooded for the first time during Hurricane Harvey. I am grateful to the Harris County Flood Control District and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for projects that were already in place along Braes Bayou by 2017. The Willow Waterhole and Arthur Storey Park projects helped lower the flood level in my home and likely saved treasured family photos and personal items that would have been ruined if the floodwater had risen an inch or two higher. While much was lost, these projects prevented even worse damage.

Such detention projects both minimize flood damage and create public green spaces. Once the water in a bayou rises to levels slightly below where flooding of homes and businesses is expected to occur, overflow structures, basically wide concrete “notches” in the side of the bayou, allow floodwater to overflow into large detention basins. These overflows limit the water level rise in the bayou until these detention basins are filled. So rather than flowing into established neighborhoods, Houston’s medical center, industrial areas, and other properties, enormous amounts of floodwater are redirected to these basins where they cause little damage. When the water levels drop, that retained water slowly and safely drains downstream.

Other detention projects, such as Exploration Green in the Clear Lake area, exist throughout Texas. While costing millions of dollars, these projects collectively save money by preventing greater flood damage. These basins offer additional benefits. My husband and I enjoy walking in the resulting parks, often used for bicycling, fishing, family gatherings, sports, and more. These green spaces build community, promote health, and create habitat.

Dow’s project in Brazoria County is the opposite of a flood mitigation project. Instead of adding detention capacity, Dow’s project would remove almost 2000 undeveloped acres from the Brazos River floodplain, reducing the area available to store flood waters moving downstream in the Brazos River. The reservoir’s walls also would block existing overflow areas which helped in previous flood events.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is currently reviewing the project. The Draft Environmental Impact Statement for Dow’s project, prepared for the Corps by contractors hired by Dow Chemical, recognizes that the “Brazos River has the largest average annual flow of any river in Texas.”

As water flows into the lower Brazos River floodplain it is measured by an existing gauge named for the village of Rosharon, just upstream of Dow’s proposed reservoir. Dow’s own report shows that 86 percent of inflow into the Brazos River during its study period came from upstream of that gauge. Dow’s report states that “the river discharge on the Brazos River is significantly dominated by upstream riverine processes rather than precipitation-induced discharges in the coastal plain.”

In simpler language, flooding in the area of the proposed project is typically driven by upstream rainfall, sometimes from hundreds of miles away, moving downstream in the Brazos River. Flood events there are not typically caused by localized rainfall.

Oyster Creek runs roughly parallel to the Brazos River. Currently during major flood events, these two streams effectively become one interconnected floodplain. Floodwaters coming down the Brazos River overflow toward Oyster Creek, which then helps convey water downstream. Most of the area between the Brazos and Oyster Creek at and near the proposed project currently becomes submerged with flowing water during floods. Again, Dow’s project would surround almost 2000 of these acres between the Brazos River and Oyster Creek with a 40-foot embankment.

When natural overflows and floodwater retention areas that have existed for centuries are blocked by this project, where will these floodwaters be redirected? What new areas will flood? How will flood water elevations and patterns change in the river nearby or downstream?

Dow’s studies fail to address these important questions.

In fact, Dow’s initial permit application to the Corps in 2018 misidentified the proposed reservoir as being in only the Oyster Creek floodplain, and not in the larger combined Brazos River floodplain that includes Oyster Creek.

As part of its review, the Corps later confirmed that “[t]he proposed Reservoir is located … within both the Brazos River and Oyster Creek 100-year Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) regulatory floodplains.” The Corps also stated that “[i]f the proposed Reservoir significantly alters the flooding on the Brazos River or Oyster Creek, the impacts to local citizens and stakeholders may be significant.”

The Corps also agreed with concerned citizens and groups, including Lower Colorado River Watch, the Brazos River Club, the Houston Sierra Club and others, that Dow needed to follow the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) process under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). This statute requires both analyzing environmental impacts from a proposed action and identifying alternatives.

But the relevance and accuracy of the information in any environmental impact statement is critical to the integrity of this process. Dow’s draft EIS seems plagued with problems.

First, Dow’s consultants separated their analysis of the Brazos River from their analysis of the Oyster Creek watershed instead of looking at both watersheds together.

Dow’s model appears to predict “no rise” in the elevation of the Brazos River once the “proposed” conditions with the reservoir are in place. But the assumptions used in the flow model don’t seem to make sense.

For example, one part of Dow’s draft EIS clearly states that existing overbank flows would be blocked and redirected by Dow’s proposed project, “which could lead to flooding elsewhere.” Yet its “no-rise” model run for the Brazos River with the “proposed” project in place appears to assume these current overflows into Oyster Creek and the related floodplain, which in reality would be blocked by the project, would continue to exist!

In this “no-rise” model, the most substantive predicted change between the “existing” and “proposed” conditions is that Dow would be pumping water out of the river to fill the new reservoir.

But those new pumps would remove up to 334 cubic feet per second from the river. In contrast, during major flood events, the reservoir might block up to thousands of cubic feet per second of existing overflows.

Dow‘s studies do not predict what will happen when floodwater arrives from upstream, hits the project embankment, and is redirected back into the river instead of overflowing into Oyster Creek. Instead, to evaluate flood “mitigation,” Dow models a “localized 50- and 100-year storm event” with rain falling on and near the proposed reservoir. This model focuses on the impacts to Oyster Creek and assumes that the new reservoir will absorb most of that rainfall. With this isolated approach, little calculated lost flood capacity results from the project.

Again, the draft environmental impact statement confirms elsewhere that the actual flood risks in this area originate upstream, and not from local rainfall. As floodwaters come from upstream, what would be the actual resulting flooding impacts from Dow’s proposed reservoir if it is constructed? We still don’t know.

My personal experience also confirms that damaging floods on the Brazos come from upstream flooding rather than local rainfall.

My personal experience also confirms that damaging floods on the Brazos come from upstream flooding rather than local rainfall.

I first met my husband’s late parents at their home in rural Brazoria County, located near the Brazos River a few miles downstream of Dow’s proposed reservoir. Our family continues to build wonderful memories here.

The river flooded the lower level of the house in 1991-92 and 1994. We then had five floods between 2015 and 2019, all much higher than the 1994 flood. All seven of these floods resulted from floodwater coming down the Brazos River from upstream, which fortunately gave us a few days’ warning to prepare by moving some things to higher ground. Yet damage still occurred and cleaning up the muddy mess left each time was unpleasant.

We fear flooding will be worse with Dow’s proposed reservoir, which removes about 2000 acres from the existing floodplain. Yet blocking the existing overflows concerns me more. If water levels increase even slightly in future floods, we will face much more serious damage to this home. We are not alone. Many rural property owners and communities, including West Columbia and others, could be affected.

In 2022, the Brazos River Club, the Lower Brazos River Watch, the Houston Sierra Club, the Bayou City Waterkeeper, and others requested that the Corps of Engineers require a Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement to address the unanswered flooding issues and other questions. The supplemental EIS should include additional information on possible alternatives to the project, environmental justice issues, climate change, effects on endangered species, and more.

On June 16, as I was finalizing this essay, the Corps posted the final Environmental Impact Statement for Dow’s project. The problematic reports analyzing flooding (Appendices A to C) were unchanged from the draft. The memos containing additional flood analysis (Appendices I to K) do not address the concerns raised above. This notice began a 30-day period to submit comments about this proposed project to the Corps. The Corps can grant the permit for Dow’s project once this comment period is completed.

If they act responsibly, the Corps of Engineers and Dow Chemical must develop more information and answer critical questions before approving or constructing this proposed reservoir. But will they?