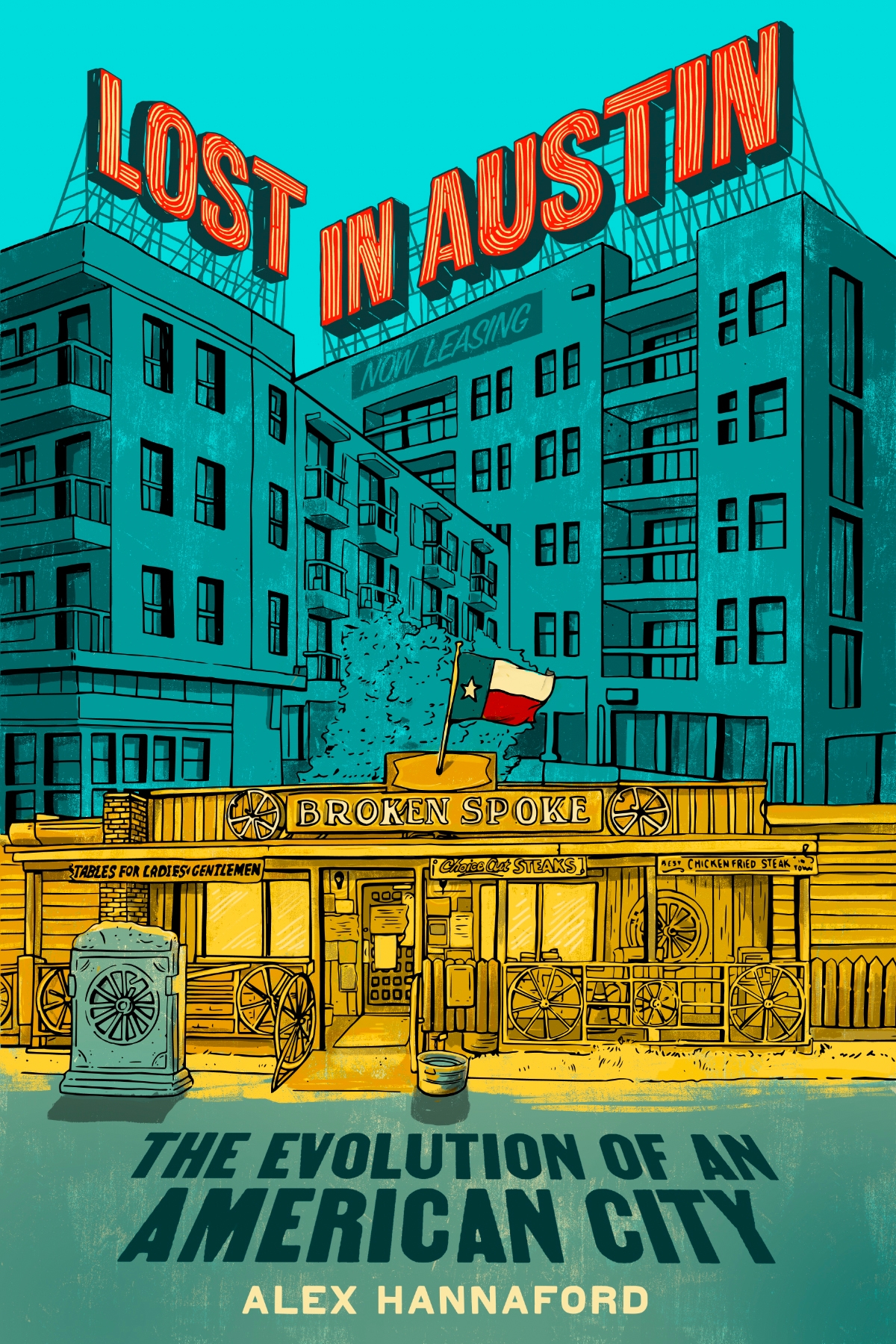

Editor’s Note: Lost in Austin: The Evolution of an American City, by longtime Observer contributor Alex Hannaford, will be published on October 1 by Dey Street Books. The following consists of an original introduction by the author followed by an excerpt, published with permission.

Lost in Austin: The Evolution of an American City is, as the title suggests, about the Texas capital. But it’s no travelog. It’s a book about gentrification and climate change and race and guns and affordability; it’s about the various tech booms that caused a rampant surge in construction and saw more people moving to a place I used to call home than it could ever really accommodate.

It’s also about how my love affair with Austin soured: For the best part of 20 years, I had a front-row seat to witness the profound changes taking place in what would become America’s fastest-growing city. And as the subtitle suggests, the book is not just about Austin, either; the themes I’ve attempted to tackle—from homelessness and the environment to how the city treats its immigrants and what the future holds—are interchangeable with so many other cities in America too.

I first stumbled upon Austin in 1999. I was on a coast-to-coast road trip with a friend of mine from England—apparently American road trips are something us Brits love to do—and we planned to take three months driving from New York (where we bought a 1988 V8 Pontiac Firebird off an undercover cop) to San Francisco, but with quite a few detours; up to Chicago, down to New Orleans, through Houston, and then on to New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California.

Austin wasn’t on our list of stops—I’d barely heard of the place, honestly; this was years before SXSW was internationally known—but someone we’d met on the East Coast insisted we go there. And so one day that May, we pulled the Firebird into the driveway of a (now defunct) youth hostel on what was then Town Lake; an unplanned visit to Austin, but one that would change my life.

I emigrated to America in 2003, and moved into an apartment in Austin. It feels like a lifetime ago. I married my Texan wife the following year, and in 2010 we bought our first home; it was on the east side and cost $165,000—three bedrooms, on a 1/4 acre lot, just four miles from downtown, and a stone’s throw from the Colorado River. Austin was a different place back then: Still affordable, and I didn’t even mind the heat. For a while.

I’m painfully aware that not only was I part of the gentrification of the east side that I would one day write about, but I was also helping promote Austin as the greatest place in the world at every opportunity I got.

While I was researching Lost in Austin, I spent hours in the Austin History Center on Guadalupe, and something I discovered there led me to telling the story of one particular district in Austin and what happened to it: Rainey Street.

Back in 1979, a neighborhood group calling itself the East Town Lake Citizens published a thin, hand-drawn black-and-white pamphlet that took the form of a comic strip. On the cover was a group of Mexican Americans sitting on the front stoop of a house, and their speech bubbles served as headlines pointing to what was inside the pamphlet. “What are you going to do when they run you out?” one man asks. “Will you still have a home this time next year?” asks another. Two women sitting on the top step ask, respectively: “Are the city’s plans for east Austin what you want?” and “Will you be able to pay your rent?” A little boy sitting next to them says, “Do you know that the Rainey St. area is now being destroyed?”

The story of Rainey Street is Austin gentrification in microcosm. Today, the district is synonymous with bachelorette parties and day drinking, with once-beautiful historic homes built in the 1800s converted into bars, now barely recognizable behind lights and awnings and beer posters. While some of the original houses were destroyed in a devastating flood in the 1930s, those were replaced with bungalows, and the community that developed there was largely Hispanic. Its prime location just west of I-35 and walking distance to downtown meant Rainey Street soon became the site of a pitched battle between developers eyeing the area for housing, hotels, and entertainment and preservationists. By the mid-1980s the preservationists had won, but it was a short-lived victory. All that effort to see Rainey Street awarded historic district status meant nothing when the city rezoned it in the mid-2000s to allow development to continue.

Brigid Shea and her husband bought a house on Rainey in 1995—a tiny one-bed one-bath that was kind of falling apart at the seams. Shortly after moving in, Brigid, who’d worked as a journalist at NPR but had turned her attention to environmental advocacy when she moved to Austin in the late ’80s, found out she was pregnant, and she and her husband spent what little money they had fixing the house up so it was livable. They knew they’d be able to stay there only a few years—their son would need a room of his own—but as a toddler he loved finding baby snakes and other creatures close to the banks of the lake, and the family liked to hike along the trail on weekends. The little house soon grew, albeit metaphorically, on Brigid and her husband. But the city was keen to rezone Rainey as commercial, and many of their neighbors were equally keen to sell their properties at a premium. One neighborhood leader, Bobby Velasquez, whose father founded Austin minicab company Roy’s Taxi in 1931, told Brigid the alternative was to sit around and watch the area slowly gentrify. “We were the only ones who said keep it residential,” Brigid recalled. “And we ultimately felt we couldn’t argue against it—it made tremendous sense for those families.”

Brigid and her family moved out of Rainey in 2001 and immediately felt homesick. Eight years later, entrepreneur Bridget Dunlap leased one of the old homes there and turned it into the district’s first bar, Lustre Pearl, setting in motion a chain of events that would culminate in this old Latino neighborhood becoming the booming entertainment area it is today. Dunlap soon launched three more bars in the Rainey Street district. Her website refers to her as the “Rainey Street Queen”—a visionary who transformed “the once residential neighborhood into one of Austin’s most sought-out entertainment and night-life districts.” She was a “pioneer,” her website said.

This idea of people thinking of themselves as “pioneers” transforming the “urban frontier” is the language of gentrification. “Urban pioneers, urban homesteaders and urban cowboys became the new folk heroes of the urban frontier,” the geographer Neil Smith wrote. “In the 1980s, the real estate magazines even talked about ‘urban scouts’ whose job it was to scout out the flanks of gentrifying neighborhoods, check the landscape for profitable reinvestment, and, at the same time, to report home about how friendly the natives were.” When a new apartment building opened in Manhattan’s Times Square in 1983, its owners took out a full-page ad in the New York Times that announced the “taming of the wild wild West.”

Brigid Shea’s house was eventually bought by a developer who built what she described as a “hideous exoskeleton” on top of it in order to expand the square footage. In 2014, somewhat ironically, the original Lustre Pearl was itself forced to close to make way for a condo development, but Bridget Dunlap opened a new spot kitty-corner to the old location on Rainey. Sad at the loss of the original building (“the one who started it all; the one who got people coming to Rainey Street”) Dunlap bought the one-hundred-year-old building off the new owner and had it transported east of the I-35 freeway. Her brand had now expanded and on its Facebook page, Lustre Pearl East is described as “the daughter of Lustre Pearl, the first darling of the Rainey Street revolution.”

In the summer of 2019, the final holdout on Rainey Street listed his family home—the one his grandparents had bought in the 1940s—for $2.6 million. Today, the handful of houses that remain on Rainey are decorated in bunting and plastic beer posters, cast in shadow on every side by high-rise apartments and hotel developments. It’s a cluster of mega towers. The Van Zandt, a hotel that, when it opened in 2015, dominated the skyline in Rainey is now dwarfed by its competitors.

I think everyone in Austin should know the story of what happened to Rainey Street and how it happened. But that thin pamphlet with the little boy on the cover asking, “Do you know that the Rainey St. area is now being destroyed?” is tucked away on a dusty shelf somewhere in the bowels of the Austin History Center.