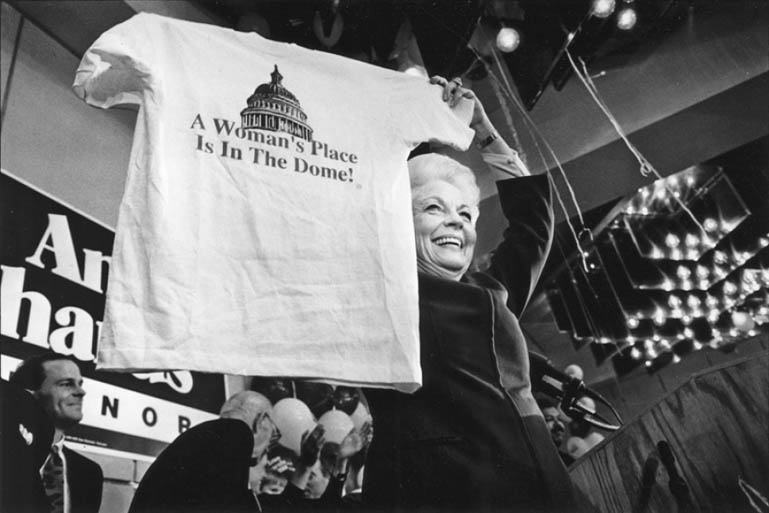

Ann Richards: A Populist and a Feminist Icon

A version of this story ran in the October 2012 issue.

In the epilogue of this fascinating biography, a 70-year-old Ann Richards recalls in an interview with University of Texas political scientist Jim Henson how her grandmother couldn’t vote at one time. “The law in Texas was that idiots, imbeciles, the insane and women could not vote. And, less than one generation later, I was the governor of Texas. Now that’ll tell you that we have progressed.”

In Let the People In: The Life and Times of Ann Richards, Jan Reid paints a nuanced picture of a pretty girl and champion debater from Waco who married her high-school sweetheart and later became a populist champion and national feminist icon. His chronicle of Richards, who died in 2006, is an absorbing tale set in a tumultuous time in Texas, and in national politics, as women and minorities pushed for greater inclusion.

Reid, an author and longtime writer for Texas Monthly, traces Richards’ 22 years in electoral politics—from Travis County commissioner to governor. The book details her experience managing Sarah Weddington’s successful legislative bid in 1972; her own candidacy for commissioner in 1976; and later for state treasurer in 1982 and governor in 1990. Richards was the first woman elected to statewide office in 50 years and the first female governor since Ma Ferguson.

Richards hit the Austin political scene in 1972, a sharp-tongued mom with striking good looks and a piercing wit. “She was sexy as all get out,” Reid remembers of the night he met her at a gonzo Bridge party of Austin liberals.

Reid captures how Richards’ self-deprecating humor—she called herself a WASP: “Waco And Sure Poor”—matter-of-fact manner and affinity for hunting, canning food and other down-home pastimes endeared her to voters who might otherwise have dismissed her progressive sensibilities.

There are also memorable scenes of Richards as an underdog in the brawl for governor in the 1990 Texas Democratic primary, as well as gaffes by cowboy oilman Clayton Williams, her Republican opponent in the general election. Joking around a smoldering campfire with members of the press on a wet night at his ranch, he compared the weather to a woman enduring rape: “If it’s inevitable, just relax and enjoy it.” The remarks outraged voters and helped propel Richards into the Governor’s Mansion.

The elective politics part of the book ends as Richards—who opened state government to women and minorities and championed gun control, environmental protection, school finance and prison reform—is unseated by George W. Bush in 1994. Reid suggests that the Bush dynasty painted a bull’s-eye on Richards’ big hair after the 1988 Democratic National Convention, where she emerged a superstar for delivering a red-meat speech on primetime TV. Of George H.W. Bush she famously drawled: “Poor George, he can’t help it. He was born with a silver foot in his mouth.”

Supporting his grudge thesis, Reid includes an excerpt of an interview with the elder Bush by The Washington Post’s Hugh Sidey, writing for Time magazine in 2004: “When George beat her in his first run for governor, I must say I felt a certain sense of joy that he finally had kind of taken her down. I could go around saying, ‘We showed her what she could do with that silver foot, where she could stick that now!’”

Reid’s familiarity with Richards’ family adds to the book’s insightfulness. Interviews with her ex-husband, Dave, to whom she was married for 31 years, and their children, mine often-painful memories. Clark Richards confesses, perhaps for the first time publicly: “When I was young, mom would sometimes have these rage attacks, and boy, they scared the hell out of me.”

Any fault with this book, which draws on more than 200 interviews conducted over three years, may lay with the absence of input from Jane Hickie, Richards’ close friend. The brusque Hickie was Richards’ administrative assistant at the Travis County Commissioner’s Office and chief of staff in the Governor’s Office. In the book’s notes, Reid writes that she “politely declined” to be interviewed. We learn little that is new of Hickie, the instigator of Richards’ alcohol-addiction intervention in 1980, which eventually led to a rehab program that successfully ended her well-known drinking problem that year.

Likewise, Richards’ self-described “steady” boyfriend after her 1983 divorce, the celebrated Texas writer Bud Shrake, overcame his alcohol addiction with encouragement from Richards and a 12-step program a few years later. Shrake died in 2009. Previously unpublished correspondence, included in the book, between Richards and Shrake reflects the poignancy of their long relationship, and reveals an affectionate and private side of Richards.

That correspondence is also filled with droll descriptions of public life, on-the-road campaign stories and Richards’ growing political cachet. Six years after her death, Richards’ story still resonates. Reid’s detailed account of her times and her legacy is a feast of vignettes and vivid characters that captures the politics that, for a time, changed the countenance of state government.

Bill Sanderson is a freelance writer and an adult education specialist for Dallas ISD teaching ESL for adult immigrants.