Afterword

Café Baviera

The bar is shaped like a horseshoe with a boy in the center. The young bartender gives Mercury’s glass an extra splash of rum, then smiles big.

“What,” the black American asks, “is your name?”

“Juan,” the boy says. “How are you called?”

“Mercury.”

“Mercurio,” the child repeats. “Mer-cur-ee-oh.”

“How old are you?”

“Eleven, yesterday. I celebrated my birthday yesterday.”

“You don’t have school today?”

“This is school,” Juan replies.

Leaning against the wall behind the counter there’s a painting. It’s a still life done in oil. Two bananas, a pineapple, two oranges, and a soft-skinned melon that Mercury has tasted, but he doesn’t know its name; in all, a bowl of fruit. Earlier, drinking his first drink, Mercury asked about the painting and Juan told him that the German lady who owns the restaurant is an artist.

Mercury turns around on his stool. He looks across the wide, wooden floor of Café Baviera. An Indian woman is setting tables for dinner. With a snap of her wrists she hangs the tablecloths out stiff in the air before the printed cotton floats down smoothly onto the table- tops.

Behind the table the walls are pale, white, and devoid of any decoration. The owner has resisted the temptation to hang her own work on her own walls. Mercury turns back to face little Juan. From the high stool Mercury smiles down at the child.

“La dueña,” the American asks, “how old is she?”

The arms of this bartender are barely long enough to serve drinks across the wide wood surface of the counter.

“I don’t know,” says the boy.

Juan calls for some milk from the kitchen. He starts to build a tall and complicated drink for a woman sitting at one of the tables in front of the bar. Mercury himself is drinking straight rum. He takes another sip.

“But she is, for example,” Mercury jokes, hoping that humor will get him the information he wants, “older than you?”

“Oh, yes,” Juan answers. “She is perhaps as old as you.”

“She is German, you said.”

“Yes.”

Every day Mercury reads the news from the capital, and every day he has seen the photograph of another Señorita Schmidt announcing her engagement at a luncheon in the German Club in Guatemala City. He has been told, but has not bothered to confirm, that the Germans arrived in the Highlands early in the last century, in an effort to get their money out of Europe before the First World War.

“Her husband is European also?”

“No,” Juan says. “He is Guatemalan.”

“He is here now?”

Juan shakes his head again. “His business is in the capital. He comes home only during the weekend.”

The child raises an eyebrow and looks hard at Mercury. Little Juan is young. But he is not innocent.

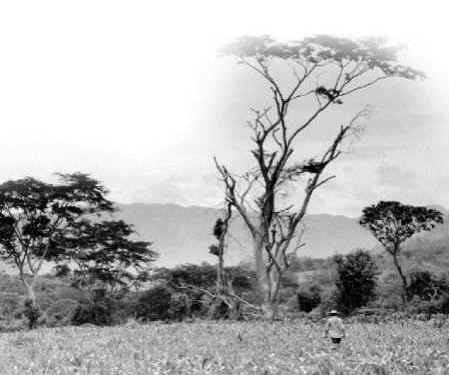

Mercury takes his drink and steps down from the stool. He drifts out onto the balcony of the restaurant. He presses his belly to the railing, just as a moment ago he was leaning against the bar. Above the tops of trees he can see Lake Atitlán. Mist floats over the surface like steam rising from a bowl of soup.

The effect of the rum and the clean mountain air is energizing, stimulating, and the result is that Mercury wants to make love. His desire centers on the German woman whom he has not yet seen. But his father’s warning about white women, first given when Mercury was only a teenager, is still ringing in his adult ears. Mercury’s father said that white women require too much “tribute.” At first Mercury believed that his father was saying that white women were too expensive to date, but Mercury’s own experience, collected as a mature adult, has been that the tribute that his father was speaking about was something other than money. Only recently he discovered what that something is.

During intimate moments, when they talked about themselves and especially about their family lives, the white women Mercury had known each revealed something, unintentionally, about themselves. They’ve used the words “princess” or “angel” to describe themselves as children.

From time to time Mercury’s white women friends have needed to be told that they were “special” to him and that Mercury was going to “take care” of them–no matter how far this was from the truth, and no matter how well the women themselves knew it. Without searching for a connection–suddenly and unexpectedly, as he broke up with his last girlfriend–Mercury finally understood what his father had been talking about. Pretending was the tribute to white skin and blue eyes that his father had refused to pay.

Mercury looks down again from the balcony. On the path between the trees leading up from the lake, two figures have appeared. One is dressed in the shiny patent leather shoes, the woven skirt, and white blouse that is the uniform of the Indian women in the western highlands. The second woman is a gringa, with red hair and pink skin.

The white woman is barefoot, dressed in a swimsuit, wearing a towel wrapped around her waist like a skirt. The pair is walking arm-in-arm, whispering and laughing like lovers.

A fisherman carrying an unlit lantern and a can of gasoline starts down the path toward the water. The two women step to either side of the sendero, to allow the fisherman to pass. When the Indian woman and the redhead begin again to walk, the wind has changed. Their conversation blows up to the balcony and to Mercury’s ears.

The redhead speaks good Spanish, a thousand times better than Mercury’s Tex-Mex. But like her painting, her Spanish is flawed. She speaks with a heavy accent. She sounds like someone trying to eat a chocolate cake and talk at the same time. At the top of the path she stops when she looks up to find Mercury staring down at her.

Today is Tuesday. In his mind’s eye Mercury can see the next few days spread out before him like the canvas inside. It should be really good–nothing will be spoiled this time.

Mercury thinks of the bare walls and the artist’s humility that blank walls implies. The German woman is too modest to be a princess. And the way she is looking at him now, certainly she is no angel.

M.L. Schamol last wrote about leaving Prairie View, Texas for the Observer (“Traveling Light,” June 23, 2000).