Review

Unjust Rewards

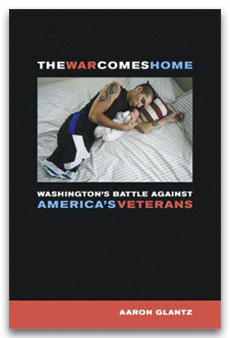

By the time you finish Aaron Glantz’s The War Comes Home, you’ll understand that one war the Bush White House was winning during its final six years was the undeclared assault on America’s veterans.

Glantz covered U.S.-occupied Iraq during three stints as a non-embedded reporter between March 2003 and January 2005. He recorded eyewitness testimonies of soldiers at the “Winter Soldier: Iraq and Afghanistan” event in March 2008 and turned them into an important book by the same name.

In The War Comes Home, Glantz systematically lays out the ways American veterans have had to struggle for their rightful benefits after serving in wars from Vietnam onward. He focuses on soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan to face understaffed and poorly maintained hospitals, Kafkaesque bureaucratic barriers, politically motivated cost-cutting maneuvers and policies designed to weed active soldiers and veterans out of the system before they can claim benefits.

Deploying statistics and case histories, Glantz makes a strong argument that our government, particularly but not exclusively during the Bush administration, aimed “to make benefits of service seem attractive to soldiers when they enlist, while extracting as little money as possible from the federal treasury” to provide those benefits. The strategy has left many dedicated surgeons, psychiatrists, nurses, physical therapists, counselors and administrators fighting their own battles on behalf of veteran patients against increasingly long odds.

The War Comes Home:

Washington’s Battle Against America’s Veterans

The odds are further lengthened by the way America’s wars are being run. Volunteer regular Army soldiers, reservists, and National Guard troops serve together without clear objectives that might boost morale, and they do so under constant threat of violence from improvised explosive devices, suicide bombers, and mortar and sniper fire. They have few tools to help them understand or sympathize with the culture in which they are immersed. Traditional “recreational” stress relievers like sex and alcohol are prohibited in Iraq and Afghanistan. Quick redeployments and the morally questionable practice of stop-loss duty extensions add to the pressures.

A Department of Veteran Affairs study of March 25, 2008, reported that 130,000 Iraq and Afghanistan veterans had been diagnosed with psychological illnesses by VA medical services. An August 2007 Department of Defense Task Force on Mental Health found that between 320,000 and 800,000 post-9/11 veterans (15 percent to 50 percent of troops who served in Afghanistan or Iraq) suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Meanwhile, Glantz reports, the number of mental health professionals in military service has declined since 2003, leading to resource overload and increasingly frequent diagnoses of supposedly pre-existing “personality disorders.” More than 23,000 soldiers were discharged on these grounds between 2001 and 2007, making them ineligible for medical services or disability benefits.

As American soldiers suffered, in 2005 President Bush appointed Jim Nicholson, described by Glantz as “a real-estate developer and former chair of the Republican National Committee who’d raised millions of dollars for Bush’s 2000 presidential campaign,” as secretary of Veterans Affairs. Then-Sen. Barack Obama later described Nicholson’s 32-month tenure: “It is clear that Secretary Nicholson is leaving the VA worse off than he found it. He oversaw one of the most tumultuous periods in recent VA history, including billion-dollar budget shortfalls, ongoing cuts in services to certain groups of veterans, and the continuation of a dysfunctional bureaucracy that keeps many veterans from getting the disability benefits they deserve.”

One excellent feature of The War Comes Home is its function as an information clearinghouse on organizations that support veterans and their families, from extragovernmental mental health resources to efficiency ratings of veteran charities to suicide-prevention hotlines.

The presence of—and need for—so many supplementary services proves Glantz’s main point, and it turns his book into something more than an exposé. It’s also a vital tool for veterans, concerned citizens, and anyone else who’d like to help rectify a national moral disgrace.

Tom Palaima is a Dickson Centennial Professor of Classics at the University of Texas at Austin, where he teaches seminars on the human response to war and violence.