The Perils of Payday

High-interest lending is a poorly regulated, billion-dollar business in Texas—and it's booming.

Isamar Lanusse doesn’t want her 14-month-old daughter, Vicky, to grow up worrying whether there will be food in the refrigerator. A 34-year-old single mom, Lanusse works 40-hour weeks driving elderly and disabled folks to their doctors’ appointments in Austin. The job earns her $27,500 a year, barely enough to get from paycheck to paycheck. But she is determined to gain financial stability.

“My mom raised us by herself on welfare,” she says. “I want to break that cycle.”

Lanusse always saw owning a home as the first step toward that goal. Four years ago, she decided to try. Needing $200 for initial paperwork fees, she found herself several days away from the next paycheck. On her way home from work, an East Austin storefront advertising payday loans caught her eye. “They said they’d give me $200 right then and there,” she says. “So I took it.”

She didn’t get the house. Instead, she found herself in deeper financial peril. “I got trapped in a cycle,” she says. When she couldn’t make payments on her high-interest loan, “they would offer me more money and then charge me 500 percent interest plus fees. It was a mess.”

Lanusse was luckier than many; borrowing money from family members and skipping utility bills, she escaped from loans that had quickly added up to $1,000. She ended up in a financial hole that’s been hard to dig out of, though. “I kept thinking I could get back on track, but it never happened,” she says. Not long ago, she qualified for a year of subsidized rent in an East Austin home.

It’s an increasingly common story in Texas. In low-income neighborhoods across the state, payday lenders are popping up on street corners and major thoroughfares at a rapid pace-from 1,513 storefronts in 2005 to more than 2,800 today. During the economic downturn, such companies as Cash America International Inc. and Ace Cash Express Inc. are racking up record profits. The largest payday lender in Texas, Fort Worth-based Cash America International, reported $1 billion in revenue for fiscal 2008-its best year ever. In all, Texans took out $2.5 billion in loans from the payday companies last year.

Federal laws designed to crack down on companies like Cash America International have backfired in Texas. In 2005, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. banned member banks from contracting with payday lenders. Soon enough, lenders discovered a loophole in a broadly worded Texas law that allowed them to operate as “credit service organizations,” or CSOs. In Texas, CSOs are required to pay only a $100 registration fee with the Secretary of State, post a $10,000 bond for each store, disclose contract terms and costs to borrowers, and allow them three days to cancel a contract. That’s about it as far as regulation goes.

Under the CSO model, payday lenders obtain loans through a third-party, “limited liability” corporation that charges 10 percent annual interest. In turn, the CSO typically charges a $20 fee for every $100 borrowed, along with a 10 percent application fee-and then interest rates that can range from 300 percent up to 1,000 percent a year.

The process usually works like this: A borrower gives the payday lender a check for the amount being borrowed, plus fees. The lender keeps the check for the term of the loan-typically two weeks-then cashes it on the borrower’s next payday. The lender requires that a borrower have a bank account and a job.

For many borrowers, it doesn’t stop with one loan. Because of fees and interest, Lanusse says, “I’d borrow $200, then need $200 more to pay my bills for the next month.”

Payday lenders say they provide a valuable service to people like Lanusse by giving them somewhere to turn in times of crisis. “If you take away payday lenders, you take away choice, and that hurts consumers,” says J. Scott Sheehan, a Houston attorney who has set up CSO businesses for several payday lenders. Without the steep interest rates, Sheehan says, “we couldn’t make a profit with a storefront business. We have retail overhead, employee payroll, and we have to lease space.”

Consumer advocates say payday lenders charge outrageous sums and feed off desperate, low-income families while taking advantage of lax state regulation. The state Legislature could tighten the regulations. Washington, D.C., and 11 states have capped interest rates at 36 percent. (In 2007, Congress capped rates nationwide at the same level for members and families of the U.S. military.) Texas cities like San Antonio, Richardson, and Mesquite have passed ordinances keeping payday lenders from operating near schools, low-income neighborhoods, and major thoroughfares.

Will the state follow suit? Not likely. In the past two sessions, Texas legislators have filed a raft of bills to rein in excessive interest rates and close the CSO loophole. Not one has passed into law. Sen. Eliot Shapleigh, an El Paso Democrat, filed four such bills during the current session. He is blunt about their prospects. “Powerful lobbyists keep these bills from ever being heard,” he says.

The industry spends millions to lobby legislators, create Astroturf “consumer” groups giving the appearance that rank-and-file Texans love their payday loans, and enrich the campaign coffers of Democratic and Republican legislators and decision-makers. No politician has benefited more from their largesse than Gov. Rick Perry, who received $29,000 from payday-lender PACs in 2008 alone.

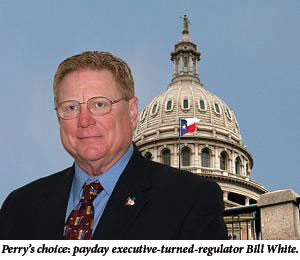

“In other states,” Shapleigh says, “governors lead the charge against these types of businesses. In our state, the governor appointed the former vice president of Cash America as the chair of the Texas Finance Commission. That tells the story right there.”

Part of it, anyway. In February, Perry named W.J. (Bill) White, former senior vice president of Cash America International, to head the commission. The panel oversees the state’s banking and lending industries, and is the parent of the state Office of the Consumer Credit Commissioner, which would more than likely regulate payday lenders if the loophole were closed. The governor declined to answer questions from the Observer for this story.

The second-highest recipient of CSO largesse is another state official with authority to rein in the industry: Attorney General Greg Abbott, who received $10,000 from payday PACs in 2008.

In 2006, Shapleigh, Consumer Credit Commissioner Leslie Pettijohn, and several consumer groups asked Abbott to determine whether CSOs were violating Texas consumer-lending laws. In other states, attorneys general already had taken action. In North Carolina, an attorney general’s suit against Ace Cash Express and other lenders had forced them to abandon business there.

Abbott declined to investigate. In a letter to Pettijohn, his office wrote: “Determining the true relationship between a CSO and a lender would be a fact-intensive endeavor.” The attorney general concluded, according to the letter, that this was an issue “that must be addressed by the Legislature.”

Last month, seven payday reform bills finally gained a hearing in Austin. Rep. Vicki Truitt, a Republican from Southlake who chairs the House Committee on Pensions, Investments, and Financial Services, created a subcommittee to look at bills that would, among other things, cap interest rates at 36 percent-and one that would shut down CSOs altogether.

The author of the proposal to close the CSO loophole was a surprise: Former House Speaker Tom Craddick. During an April 14 hearing, the longtime Republican legislator from Midland explained why. Linda Lewis, the 53-year-old former employee of Paul Davis, an influental Midland businessman, had racked up $12,000 in debt after borrowing $6,300 from an auto-title lender to pay for her stepson’s funeral. Lewis had turned to Davis for help, and he paid off the debt. Word got around. It caused a stir in Craddick’s backyard.

“I’m getting an earful from my constituents on this bill,” Craddick told the subcommittee. As he spoke, the payday lobbyists who’d packed the hearing room appeared unfazed, tapping away at their BlackBerries. Before he testified, Craddick circulated among them just like old times, chatting up some of the payday lobby’s biggest players, including former House Speaker Gib Lewis, superlobbyist Rusty Kelley, and Bill Messer, a Craddick ally and member of the powerful lobby firm Texas Capitol Group.

The lobbyists had other reasons to feel assured. Two of the three subcommittee members had received campaign contributions from payday PACs. Chair Dan Flynn, a Republican from Canton, got $5,000. (In 2005, Flynn filed a bill to increase the allowable interest rates on payday loans.) Subcommittee member Tan Parker, a Republican from Denton, received $1,500 for his 2008 campaign.

If any of the reform bills got through the subcommittee, they would go to the House committee chaired by Truitt, who got $1,500 in campaign money from payday PACs last year. Democratic Rep. Rafael Anchia of Dallas, the vice chair of Pensions, Investments, and Financial Services, received $1,000 during his last campaign. On the Senate side, Republican Troy Fraser of Marble Falls, who chairs the Business and Commerce Committee overseeing CSOs, received $3,500. Vice Chair Chris Harris, a Republican from Fort Worth, took $7,000 from payday PACs.

Even some authors of CSO reform bills have gotten money from payday lender PACs. Rep. Marisa Marquez, a first-term Democrat from El Paso who is carrying one of the bills, got $1,000 in 2008. “The checks I receive for $50 or $25 dollars from my constituents have a lot more impact than a PAC check,” she says. “Ultimately, it’s about safeguarding my community, and $1,000 won’t change that.”

If the 15 lobbyists who testified at the April 14 hearing couldn’t convince the subcommittee that payday loans were a blessing in disguise for working Texans, they had another weapon: Michael Price, senior pastor of the Gates of Dominion Word Ministry International. Pastor Price told the panel that in addition to his ministerial role, he serves as president of the Texas Coalition for Consumer Choice, which claims 45,000 members. Members, he testified, had given him permission to speak on their behalf in opposition to the CSO reform bills. Payday lenders, Price said, provide a valuable service to his fellow African-Americans in Texas by offering loans to people in a financial pinch.

Questioned after the hearing about what had driven him to create his coalition, the pastor was evasive. “It was an evolutionary process that started about six months ago,” he said. Price said he’d become convinced that payday loans keep low-income mothers and fathers from sending their children out to sell drugs or engaging in prostitution. Asked whether the CSOs were giving him any financial compensation, Price answered, “Not directly, but indirectly, because I want them to stay around.” He declined to say more.

The coalition’s Web site is crisp and professional. It calls the coalition “a growing group of consumers, businesses, trade groups, churches and others that believe customers are best served when provided a variety of options and allowed to make informed financial decisions based on what is best for them and their families.”

A check of the site’s domain owner reveals that it’s paid for by lobbyist Tim von Kennel. At the April 14 hearing, von Kennel testified against the reform bills on behalf of the Consumer Service Alliance of Texas, a trade association representing some of the largest CSOs in the state. Among them: Ace Cash Express and Cash America International.

Fighting for payday-loan reform can be exasperating for consumer advocates of the grassroots variety. After the April 14 hearing, Alfredo Chaparro, a Midland resident who testified against the payday lenders, called it “an eye-opening experience. The room was filled with corporate lobbyists. I’d only seen things like that in the movies. I felt like I was going up against big tobacco.”

At a second House subcommittee hearing on April 21, George Human, a retired civil engineer, testified that through his church he’s voluntarily counseled dozens of neighbors who are struggling with debts from payday loans. “We have a list of at least 30 places people can go to get emergency services and loans” without the high interest rates, Human said.

He told the subcommittee about a man who came to him after borrowing $100 from a payday lender to buy medications for his mother. Human said the man had ended up paying more than $1,000 in interest and fees. He still owed $460 dollars when he turned to the church. “The people that are running these companies are really hurting people,” Human said. To illustrate the problem, he submitted a redacted copy of the man’s contract to the subcommittee.

Rep. Flynn, the subcommittee chair, was not sympathetic. “The disclosure is there-it’s very prominent. I can read it without my glasses,” he said. “Do they not realize what they are doing? Is it because of education? Because it looks like the disclosure is there.”

At the end of the day, Flynn left the reform bills pending. Legislative action may have to wait until 2011.

Isamar Lanusse doesn’t get it. “I don’t know why they don’t regulate them,” she says. With the recession deepening, she has noticed more and more payday lender signs sprouting up in her East Austin neighborhood. “You see them on just about every corner now.”

These days, Lanusse is taking financial classes and slowly repairing her credit so she can one day buy a house. She warns her neighbors and co-workers to avoid the trap she and so many other Texans have fallen into. “I tell my friends, don’t do it,” she says, “because you’ll be sorry. Look at what happened to me.”

Investigative reporting for this article was supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Institute.