Muhammad Rocked the Casbah

San Antonio's Muslim punk scene goes national, and Europe is next.

This article has been updated to correct the location of the Islamic Society of North America conference. Last update: December 18, 2007

Kourosh Poursalehi was a 16-year-old Sufi from San Antonio in 2004 when he created a song that made a fictional punk-rock movement come alive. Hypothesizing that no one in the world was like him, Poursalehi went looking for other Muslim punks and discovered The Taqwacores, a novel written by Muslim-convert Michael Muhammad Knight about a fictional underground Muslim punk-rock scene in upstate New York. In the book, the punks called themselves taqwacore-a combination of the Arabic word taqwa, meaning consciousness of God, and hardcore.

Poursalehi thought the taqwacores were real and set out to meet them. He found a poem written by Knight at the beginning of the book called “Muhammad was a punk rocker” that portrays the Prophet rebelling against the oppressors of his time, smashing idols and sporting a spiky hairdo. Poursalehi put the poem to music-spawning the first-ever taqwacore song.

The poem embodies Knight’s vision of Muslim punk. Born in the 1970s, punk rockers purposefully sing off-color lyrics, wear politically incorrect labels, and stamp their bodies with tattoos in the name of individual freedom and opposition to the status quo. The Prophet Muhammad was punk, according to Knight, because he was a nonconformist who fought for what he believed. A growing number of young Muslims who resist their parents’ orthodox views, but also struggle with the values of their non-Muslim friends, are embracing punk. Muslim punk provides a place to forge a new identity for young Muslims confused about religion and their role in American society, particularly as they are bombarded by negative stereotypes of Muslims in a post-9/11 America. At the same time, Muslim punk offers a palpable way to express anger toward the orthodoxies of fundamentalist Islam.

Once Poursalehi completed his song, he sent a recording to Knight, who lives in upstate New York. Knight had written “Muhammad was a punk rocker” after returning from Pakistan, where he studied Islam for six hours a day and almost joined the Chechen mujahedeen before growing disillusioned with his faith. As a Muslim, Knight felt trapped. Whenever he questioned his faith, other Muslims accused him of having “no adab,” which translates in Arabic to “no manners.” He discovered punk in college and fell in love with its philosophy of never apologizing for having a different point of view. Still, he yearned for a spiritual life. He wrote “Muhammad was a punk rocker” and then the novel, fantasizing about a place where Muslims would accept him. When Knight heard Poursalehi’s song for the first time, he was ecstatic.

“I had it play on repeat over and over, and I couldn’t believe what was happening,” Knight said. “I had just put something out there into the world, not knowing if it’d have meaning for anyone else, and then here I was listening to this kid sharing it, making it his own.”

A few days after hearing Poursalehi’s song, Knight took a road trip to Boston to meet Shahjehan Khan and Basim Usmani. Both would gain worldwide recognition as the lead guitarist and singer, respectively, for a Muslim punk band called The Kominas. Khan and Usmani had also recently read The Taqwacores and had contacted Knight to share their admiration for the book.

A self-described Muslim delinquent, Khan met Usmani playing hooky from Sunday school at their mosque in Wayland, Massachusetts. Khan had a fairly sheltered childhood in a suburban town outside Boston. It wasn’t until he enrolled in the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, soon after September 11th, that he experienced prejudice. Khan said “weird barriers” arose between him and other students-he found the cafeteria ethnically divided, and his floormate went so far as to tell Khan that Muslims cause all the problems in the world. Following a two-month drug binge, Khan dropped out. He moved home and enrolled in the University of Massachusetts at Lowell, where he and Usmani rekindled their friendship. Usmani had just read The Taqwacores, and he gave Khan his copy. The book reawakened Khan’s interest in Islam-for the first time he felt he could identify with Muhammad as someone who had also struggled against society to make his own way.

“I started thinking maybe I was Muslim all along,” Khan said. “Part of being Muslim is questioning authority and making mistakes and blazing your own trail.”

Khan remembers that Knight pulled up to Usmani’s house in Lexington, Massachusetts, blaring “Muhammad was a punk rocker” with the windows on his green Buick Skylark rolled down. He lived in the car at the time, and had a makeshift bed in the backseat. Usmani and Khan climbed inside the car and spent the afternoon driving around listening to Poursalehi’s song. Usmani had recently introduced Khan to punk and burned him a CD called “Punk 101.” They had taken a stab at writing music together, but had yet to finish a song. “Muhammad was a punk rocker” demonstrated that there were like-minded Muslims out there.

“It was nuts,” Khan said. “I couldn’t believe there was this kid down in Texas writing this music. I don’t remember what my exact feeling was at the time, but I remember I was excited and thinking that this was the beginning.”

San Antonio, with its small Muslim population, may seem an unlikely birthplace for Muslim punk. Given San Antonio’s dominant culture, however, it’s understandable why Poursalehi would embrace taqwacore. Poursalehi grew up thinking no one was like him. Traveling to his house in northern San Antonio, it’s easy to see why. On a 10-mile stretch of Stone Oak Parkway, there are at least 10 churches, several Christian schools, and billboards proclaiming, “Jesus is Lord.” The Cornerstone Church, a 17,000-member Christian-Zionist megachurch, sits at Poursalehi’s exit, and several more churches lie along the main road to his house. Out of San Antonio’s 1.2 million people, the Catholic Diocese of San Antonio alone claims 680,000 members, and the San Antonio Baptist Association has 265 church affiliates. By contrast, 30,000 Muslims live in San Antonio, including recent converts.

Poursalehi went through his teenage years during a time that this small Muslim community felt under siege. Sarwat Husain, who chairs the Council for American-Islamic Relations in San Antonio and collects data on hate crimes in the area, said discrimination against Muslims reached its peak immediately following September 11. Four Muslim-owned gas stations were torched, women donning burqa were physically attacked on the streets, and children were beaten up at school. While hate crimes against Muslims still occur, Husain said the community now has more support from city leaders.

As a Sufi, Poursalehi faced double discrimination. Narjis Pierre, a Sufi and author living in San Antonio, said that Muslim immigrants sometimes bring misconceptions about Sufis from their homelands. Often described as a mystical tradition within Islam, Sufism began in resistance to corrupt Islamic rulers. Sufis have continued to resist oppressive regimes in the modern era (for example, the predominantly Sufi Kurds in Northern Iraq fought Saddam Hussein). As a response to their resistance, Pierre said, rulers have marginalized Sufis, deeming their faith heretical. “In many countries, Sufis have been seen as innovators and heretics, and this ‘ignorance’ may be carried over to Europe-America and given on to their [Muslim immigrant] children,” she said.

Poursalehi never shared his Sufi upbringing with his peers. He continues to be reluctant to discuss his Sufi background. He says the religion bothers him because it’s too closely tied to money. In spite of his resistance to Sufism, Poursalehi admits it influenced him. He even credits religion with piquing his musical interest through the Sufi practice of dhikr, which involves remembering God through chanting divine names. Often Sufis achieve an ecstatic state with dhikr. Poursalehi describes music as a similarly mystical experience.

“Music is like another world for me,” he said. “It’s like when you’re a little kid and you think of a fairytale land. That’s how strong music is for me.”

Poursalehi found punk music at age 14. He started listening to The Fearless Iranians from Hell, a San Antonio punk group that has striking similarities to many taqwacore bands. The Fearless Iranians would perform with ski masks to make fun of stereotypes about Muslims being terrorists. Around the time Poursalehi discovered punk, San Antonio had a lively punk-rock scene. Poursalehi supported local bands and regularly attended concerts at venues such as Sin 13 and Sanctuary. He said he found a connection between punk shows and religion.

“In both areas, there’s a strong sense of energy going around and unity almost,” he said. “It’s about people coming together for the same cause and the same concerns. It was crazy hearing a live show. It put chills through your body, and I decided I wanted to do that.”

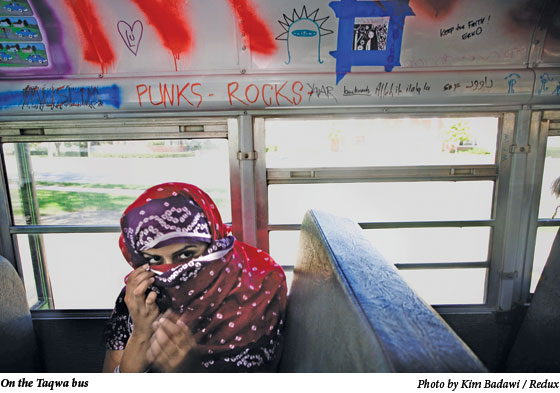

It’s been three years since Poursalehi made the first taqwacore song. Since then, he has created a punk band called Vote Hezbollah (the name’s a joke), the Kominas have established a cultlike following, and numerous other taqwacore bands have sprung up across the country. The Muslim punks have established relationships online. Last summer they all met on the first-ever Muslim punk-rock tour. Knight bought a bus for $2,000 on eBay, painted it green with small red camels, and wrote “taqwa” on the front. Five bands, including the Kominas and Vote Hezbollah, toured for 10 days from Boston to Chicago.

During the trip, the Muslim punks encountered the same issues they have struggled with separately. The Islamic Society of North America invited them to perform at its conference in Chicago. For the first 10 minutes, the concert was a success-young Muslims packed the conference, cheering the taqwacore bands from their respective male and female sections. But when a female group, Secret Trial Five, took the stage, conference leaders called the police and had the taqwacore bands kicked out-Muslim women are forbidden to sing in public. The taqwacore groups also had to deal with discrimination. On the road, other drivers flipped them off. One driver held a “Fuck Allah” sign up to his window.

This time, however, rather than bottling up their anger, the Muslim punks responded with humor, mostly dark. The Kominas performed songs with provocative lyrics such as “suicide bomb the gap,” and “Rumi was a homo” (a stab at an anti-gay imam in Brooklyn). The musicians started a joke band named Box Cutter Surprise, after the knives used to hijack planes on September 11th. Marwan Kamel, from a band on tour called Al-Thawra, Arabic for “revolution,” said members created the group to shock audiences.

“The sole purpose was to light a fire under people’s asses,” Kamel said. “We were totally exploiting Americans’ fear of terrorism, but maybe that’s what everyone needs right now.”

On tour, the taqwacore bands allowed each other to embrace their contradictions as young Muslim Americans confused about their religion, identity, and place in the world. They prayed together, philosophized about Allah, visited mosques in Harlem and Ohio, shouted their grievances about President Bush, and generally thought for themselves.

“I began to feel a balance between my identity as a Muslim and an American,” Khan said. “It was literally the most amazing experience of my life.”

This fall the Muslim punks returned to their homes across the country. Some of the bands, like the Kominas and Vote Hezbollah, are working on albums, and they’re all planning a European tour next summer.

Other Muslims have picked up their guitars and turned up their amps, and more bands promise to join the taqwacores on their trip. Jeremy (who doesn’t use a last name and also goes by Bilal) is a Muslim-convert from Fort Worth who recently started writing punk music. He converted to Islam after attending Baptist Middle School, where his teachers rarely gave him satisfactory answers to his questions about the Bible (such as, why can Christians eat pork?). He went on a spiritual quest and came across The Taqwacores. Then he began talking to Knight and other Muslim punks online. Jeremy dreams of writing music that will spread a peaceful image of Islam. The first taqwacore song to inspire him? “Muhammad was a punk rocker.”

“I think all the prophets and imams were punk rockers,” Jeremy said. “They were all labeled as weird; they all fought against the evils that had become common in their societies. They were all persecuted … Abraham broke idols of wood and stone, and Jesus broke conceptual idols, and Muhammad broke both.”

Lydia Crafts is a freelance journalist. She recently relocated to Austin from the northeast.