Sticking Point

International treaty obligations are keeping Josè Medellin off the death house gurney

In all likelihood, the state of Texas will eventually kill José Ernesto Medellin. Even the best possible outcome of his recent U.S. Supreme Court case will leave the convicted murderer’s fate in the hands of the Texas Criminal Court of Appeals, where many a death row appeal has perished – literally and figuratively.

In the meantime, Medellin – and 53 other Mexican nationals sentenced to death in the United States -have created a judicial train wreck that has ensnarled state, federal, and international courts of law for more than a decade. Medellin’s case offers a smorgasbord of meaty issues for constitutional law experts to debate, from states’ rights to presidential and Supreme Court powers and the nature of U.S. treaty obligations. It has pitted the United States against Mexico and much of the Western world, Texas against the federal government, and President George W. Bush against erstwhile conservative allies. It has once again set the liberal and conservative factions on the Supreme Court at each others’ throats. As if that weren’t enough, the outcome of the case could have implications for the protections U.S. citizens can expect when traveling abroad.

Medellin v. Texas provides something for everyone to fear. Some commentators warn ominously of creeping one-world government complete with internationally mandated gay marriage and environmental regulations. Others express alarm over yet more erosion of U.S. credibility on the world stage and the trampling of individual rights on American soil.

It probably all could have been avoided, if the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals didn’t have such a stubborn streak.

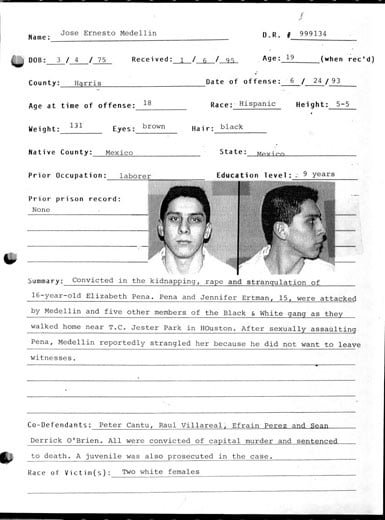

The case began on June 29, 1993, when Medellin was arrested by Houston police who suspected he had taken part in the gang rape and murders of 14-year-old Jennifer Ertman and 16-year-old Elizabeth Pena. After two hours in custody and having been informed of his Miranda rights, Medellin gave police a written confession. The following year, he was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death.

It looked, at least by Texas standards, to be an open and shut capital case. But three years later, a wrinkle emerged. When he was arrested, the 18-year-old Medellin told authorities that, while he had been raised and educated in the United States, he was a Mexican by birth. According to Article 36 of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations- to which the United States has been a party since 1969 – detained foreigners must be told “without delay” that they have a right to let their consulate know they have been arrested. Medellin did not know of this right, and Houston authorities were either also unaware or unwilling to clue him in.

Medellin contacted Mexican officials in April 1997, and they began providing him with legal assistance. Medellin began raising violations of the Vienna Convention to challenge his conviction and sentence, but the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals ruled against him. In 2001, he appealed in federal court, and once again lost.

While Medellin’s case was working its way up the federal court food chain, Mexican officials were becoming exasperated that many states were ignoring the Vienna Convention. Mexican citizens were being jailed across the country with no opportunity to contact a consulate. On behalf of Medellin and 53 other Mexicans on U.S. death rows, the Mexican government filed a complaint in the International Court of Justice – the United Nations’ primary judicial body. Both Mexico and the United States were parties to the Vienna Convention’s Optional Protocol, which granted the ICJ authority to settle disputes between nations over application of the treaty.

On March 31, 2004, the ICJ issued its opinion in the Case Concerning Avena and Other Mexican Nationals, holding that U.S. courts must review and reconsider the convictions of 52 Mexican nationals (two had already been removed from death row), having examined “the facts, and in particular the prejudice and its causes, taking account of the violation of the rights set forth in the [Vienna] Convention.” The ICJ wasn’t saying the sentences of Medellin and others should be thrown out. Rather, it was asking U.S. courts to reopen the cases to allow a good-faith examination of whether complying with the treaty might have changed the outcome.

Although it wasn’t the first time the international court had heard challenges to U.S. death sentences for foreign nationals, it was the first time the ICJ managed to issue its final judgment before the individuals in question were executed.

Despite the Avena ruling, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit upheld Medellin’s conviction. The U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear the appeal.

Before oral arguments took place, however, Bush issued a memorandum to then Attorney General Alberto Gonzales stating that “the United States will discharge its international obligations under the decision of the International Court of Justice … by having State courts give effect to the decision in accordance with general principles of comity ….”

In light of the president’s order, the Supreme Court kicked Medellin’s case back to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals for further consideration based on Avena and the president’s memorandum. (The following year, the high court ruled in a case from Oregon that incriminating statements made prior to consular notification were admissible in court and that the Avena decision was not binding on U.S. courts, but it did not address the status of the 52 Mexicans directly involved in the ICJ case.)

Back in the hands of Texas’s highest criminal court, the case could have gone quietly away. The Texas judges could have agreed to reconsider the case. They could have concluded that Avena or the presidential memorandum constituted new information that allowed them, under Texas law, to review Medellin’s conviction and sentence. In Oklahoma, where two of the affected Mexicans were imprisoned, that’s exactly what happened: The state courts reviewed the cases, and the governor commuted the death sentences. After taking another look, the Texas court could even have ruled that the Vienna Convention violations did not prejudice the verdict and sentence, and let Medellin proceed on his way to lethal injection.

“I think it would have been far easier and a better result had they ordered a reconsideration pursuant to the presidential order, because that really doesn’t require a change in result,” said Ed Swaine, an associate law professor at George Washington University and a former legal advisor to the State Department. “That’s what the Supreme Court thought might happen when they remanded previously. I think that would have been easier on everyone concerned.”

Instead, in an opinion issued on November 16, 2006, the Texas court unanimously told the ICJ exactly where it could stick its Avena decision. The Texas court would not reconsider anything. Although a majority of the judges couldn’t agree on the exact legal reasoning, they also unanimously held that the president should keep his memorandums to himself. Medellin v. Texas was back on the fast track to the U.S. Supreme Court, which accepted the case again on April 30, 2007, and heard oral arguments on October 10.

Donald Donovan, Medellin’s attorney, was first to appear before the nine Supreme Court justices, and he plunged straight into international waters. Through the Optional Protocol, Donovan argued, the president and the Senate had committed the United States to heed the ICJ in disputes arising from the Vienna Convention. It was the responsibility of state courts to honor this obligation by reviewing the trial records of the 52 Mexicans named in the Avena decision to determine whether lack of notification harmed their defense. Medellin’s case deserved another look, he said, and the Supreme Court should order the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals to give it one.

U.S. Solicitor General Paul Clement followed Donovan to the podium, and he had Donovan’s back – albeit conditionally. Clement argued that it was up to the president, and the president alone, to determine whether the United States should heed the ICJ judgment. If the president had decided to buck the international court, Clement said, he’d be standing over on the Texas side.

Finally, R. Ted Cruz, who after over four years as Texas solicitor general is now a seasoned high court veteran, had his turn, arguing that the Supreme Court shouldn’t let the ICJ or the president tell it what to do – and nobody should tell the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals how to run its court. If Donovan had his way, the United States would be dangerously ceding its sovereignty. If Clement’s arguments prevailed, the president would be given unprecedented power.

And so, with fundamental constitutional issues hanging in the air, the court launched into a roiling discussion on the relative powers of states, the president, and the high court itself. The justices seemed to relish the debate, and in a rare nod to the complexity and import of the case, Chief Justice John Roberts gave Donovan an extra five minutes to answer their questions – and then allowed Clement and Cruz to also go over. In all, arguments ran long by nearly 30 minutes.

As the justices took their seats on the bench, knowledgeable eyes were on Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg – who the previous year had broken ranks with her liberal brethren and sided with the conservative majority in the Oregon consular notification case – and Justice Anthony Kennedy, the conservative justice most likely to be swayed by arguments for presidential power or respect for international tribunals. While it became clear early on that Ginsburg had likely returned to the fold, Kennedy remained a cipher.

As Donovan began his presentation, Justices Antonin Scalia and Roberts were first out of the gate, peppering the lawyer with questions about the scope of the ICJ’s power.

What if the ICJ decided that the Houston police officers who didn’t tell Medellin his rights should be sentenced to five years in prison, Roberts asked, getting to the question of just which court rules this land. Wouldn’t the U.S. Supreme Court have the power to review that ruling?

Donovan struggled with the hypothetical until Ginsburg and Justice Stephen Breyer stepped in. “Does the ICJ ever issue a judgment of that character?” Ginsburg asked. “If the ICJ were to do something which it had never done, like, say, put everybody in jail for 50 years … I guess that might violate something basic in our Constitution, in which case we wouldn’t enforce it,” Breyer noted.

Donovan was asked, Does the federal government, through law or treaty, ever have a role meddling in the procedures states use to run their criminal courts? Scalia didn’t seem to think so. Justice David Souter noted that all the federal government was asking Texas to do in the Medellin case was reopen it enough to at least consider the Vienna Convention obligations. No one was trying to tell Texas courts to throw out Medellin’s conviction or sentence.

Perhaps the most discouraging development for Medellin came when Kennedy noted the ambiguity of the Avena decision and said he thought Texas had given Medellin “all the hearing that he’s entitled to under this judgment ….”

Donovan’s arguments ended with Roberts pouncing on his statement that the Supreme Court had the authority to enforce U.S. treaty obligations even if the president didn’t agree. “Well, if we have the authority to determine whether the treaty should be complied with in the face of a presidential determination, why don’t we have the independent authority to determine whether or not it should be complied with as a matter of federal law without regard to the president’s determination?” Roberts asked.

This set the stage for Clement, whose job it was to convince the justices that the president’s opinion mattered; in fact, it was the “critical element” in this case.

Scalia questioned whether “the president can make a domestic law by writing a memo to his attorney general.” Justice Samuel Alito added, “If we agree with you, would the effect be that the president can take any treaty that is ratified … and give it force under domestic law?”

Clement laid out the heart of the administration’s argument: The president can’t displace the Supreme Court. But if the president decides to comply with an international tribunal’s judgment, “the role of this court is limited to deciding whether there was jurisdiction to issue that judgment in the first place; and then the secondary role of this court would be to say, does the rule of law embodied by that judgment violate the Constitution?”

Clement concluded by defending the power of the presidential memorandum, even though it was directed to the attorney general and not the states: “Obviously, from the very beginning in this case, we have taken the position in this court that the president’s memorandum directs the state courts, in its words, to give effect to the Avena judgment – not decide whether you want to give it effect … but to give effect to the judgment.”

Shortly after Cruz began his oral presentation, Justice Stephen Breyer noted that the Constitution requires treaties the United States enters into to be the “supreme law of the land,” which should be binding upon judges in every state – “I guess it means including Texas,” he remarked wryly.

Cruz responded that, in this case, the treaty was not “self-executing” because Congress failed to pass supporting legislation to give aggrieved parties legal recourse in U.S. courts. And in any regard, any treaty that “purported to give the authority to make binding adjudications of federal law to any tribunal other than [the Supreme] Court … would violate Article III of the Constitution.”

But what about the 112 treaties and 116 international regulatory entities the United States has joined, Breyer asked. “Is your view [that] all of these thousands – perhaps hundreds, anyway – of treaties are unlawful, and that our promises are not enforceable because there’s a constitutional question?”

“In those instances, the bodies in question are not making definitive interpretations of what federal law is,” Cruz replied.

“The entire purpose of this adjudication,” Cruz continued, “is not to resolve something finally in a court of law, but it is rather a diplomatic measure ….” He compared it to the United States bringing an ICJ case against Iran during the hostage crisis in 1979. “We didn’t believe the Ayatollah was going to listen to the ICJ and suddenly let the hostages go … but it was helpful diplomatically to bring it to the tribunal to then [apply] international pressure.”

Later in the arguments, Kennedy posed another hypothetical that could give insight into where he may come down on the case. What if a judge refuses to allow a defendant to contact his consulate, Kennedy asked. Could you order that judge to allow notification? Cruz said no.

“If I thought he did, would I still have to rule against you?” Kennedy responded. Cruz replied that, in this case, there was no evidence of a deliberate violation of the Vienna Convention.

After the arguments, Cruz and Donovan stood before the press on the steps of the Supreme Court and tried to claim the moral high ground.

p>”The president a

d the Senate made a basic commitment to this country’s most basic values, which is a commitment to the rule of law,” Donovan said. “The ICJ delivered a very modest judgment in which it directed the United States to reconsider these judgments. And now the president has said we’re going to comply with that judgment. That is actually expressing the will of the American people, because the American people believe, like the president, that a deal’s a deal.”

He then warned that if the United States disregarded its duties under the Vienna Convention, it could endanger Americans who travel abroad. “The United States doesn’t want there to be any question about its own commitment to the rights that it asks other countries to enforce,” he said. “The access of American nationals to their consular offices when they’re abroad is a very important right – it’s a bread and butter way that consular offices protect their nationals.”

Meanwhile, Cruz imagined Texas as Horatius at the bridge, fighting to keep meddling globalists at bay. “If the World Court has the ability to trump the Supreme Court of the United States, that will gravely undermine the sovereignty of the American people,” he said. “And Texas is committed to vigorously fighting to defend the sovereignty of both Texas and the United States.”

Later, Cruz noted that giving the president power to pick and choose which treaties and international judgments to enforce could open the door for “enormous mischief.” And although Bush has withdrawn the United States from the Vienna Convention’s Optional Protocol, another president could always attempt to rejoin it – or find new international authorities to cite as justification for achieving domestic policy goals. It’s just such a possibility that has many conservative legal scholars twitching nervously.

“Whether that is, for example, environmental laws or tort laws or … marriage laws or adoption laws or death penalty laws, if the president has the authority to write a two-paragraph memorandum to a member of his or her Cabinet and, with a stroke of a pen, set aside state law, that undermines the basic separation of powers that protect the liberties of all citizens,” Cruz said.

The high court’s decision is expected sometime early next year. If oral arguments are any indication, the court will be closely divided. A win by Texas would allow Medellin’s execution, and those of the 14 other affected Mexican citizens on Texas’s death row, to proceed. Depending on the legal reasoning behind its ruling, a win by Medellin could greatly expand the scope of presidential power or the domestic reach of U.S. treaties – although few will be shocked if the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals subsequently finds Medellin’s conviction and death sentence unaffected by his lack of consular notification.

Regardless of the outcome, the case has made for some strange legal bedfellows. “Many people who are generally in strong favor of presidential authority in foreign affairs don’t like the degree to which this intrudes on the authority of the states,” said George Washington law professor Swaine. “And many who generally favor international institutions likewise have some qualms about how drastic this kind of remedy would be and how much it opens the door up for presidential authority.”

The case has even set Cruz, a former Bush Pioneer fund-raiser, campaign advisor and Justice Department counsel, against his old boss. When asked if this has affected his relationship with the president, Cruz paused and replied, “I’ve got no comment.”

Anthony Zurcher is a writer and editor in Washington, D.C.