Educating Mendy

by Barbara Belejack

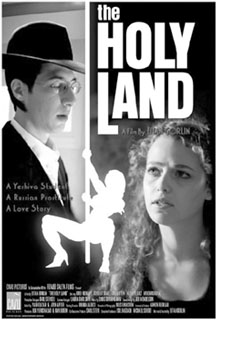

Do you believe in fate? Do you believe in God? Where does God live? For one brief moment the two young protagonists of The Holy Land walk hand in hand, gamboling through Jerusalem and posing life’s big questions. If we didn’t know better we’d say that they were just an ordinary young couple spending their Junior Year Abroad, taking in a bit of Biblical antiquity to round out a nice liberal arts education. Instead, Mendy (Oren Rehany) is a troubled yeshiva student from the Israeli hinterland whose rabbi has ordered him to take a brief hiatus so that he can “get it out of his system.” Sasha (Tchelet Semel), his lovely companion, is a prostitute from Ukraine who thinks she will work for a few months, go back home, fall in love, marry a nice boy, and forget “it” ever happened.

In making the film, first-time director Eitan Gorlin has borrowed liberally from the Bible, the Buddha, and his own experience. Born in Washington, D.C., he was raised an Orthodox Jew and graduated from an all-male yeshiva steeped in the centuries-old tradition of Eastern Europe. After graduation he traveled to Israel, where he lived off and on for several years and through several incarnations—as a serious yeshiva student, a partisan of radical Zionist settlers, a soldier in the Israeli Army, and a bartender in a legendary Jerusalem bar called Mike’s Place. Filled with the flotsam and jetsam of the hippie trail and the Holy Land pilgrimages—not to mention local Arab and Jewish patrons sitting side by side—Mike’s Place inspired Gorlin to write a novella and make a film. Alas, the bar no longer exists; it was bombed this spring. The novella is still unpublished.

The Holy Land opens with what have become all-too-familiar images of generic violence in Israel and the West Bank. Sirens wail, protestors torch an Israeli flag. We hear a voiceover of a woman speaking English with a heavy Eastern European accent. “My mother told me not to come to Israel,” she says. “That the only reason Jews bring Russians to Israel is to do dirty jobs that Arabs won’t do because of the fighting.” Later we learn that the voice belongs to Sasha, superbly portrayed by Semel, an Israeli actress who does not speak Russian (nor Ukrainian), but has obviously taken classes at the Meryl Streep School of Foreign Accent Acquisition. Men in the Middle East, she continues “are primitive and stupid. They treat women like dogs. Worse than dogs.” As far as she’s concerned, they can all kill each other, Arabs and Jews alike.

Meanwhile, back in the hinterland, 20-year-old Mendy is moody and distracted. The son of an ultra-orthodox rabbi and an American woman, he can’t concentrate on his rabbinical studies. As the family prepares for their Shabbat meal, he’s busy in the bathroom with a Hebrew porn magazine. When he’s supposed to be studying the Torah, he’s reading Hermann Hesse. His rabbi takes him to task, then quotes from an obscure passage of the Talmud and suggests that he go to another town “and visit a harlot,” the remedy proscribed for “extreme cases.”

Mendy quickly takes him up on his offer. At the Love Boat, a Tel Aviv strip bar, the painfully shy young man meets Sasha. After a brief attempt at awkward small talk—So, do you like working here?—he enjoys an even more brief, yet sufficiently successful, 30-second encounter. He later meets Mike (Saul Stein), an expatriate American and former war photographer who barrels about Israel dressed in standard-issue flak jackets, boasting that he owns “the craziest bar east of Sarajevo—where I’d be right now if it weren’t for those fucking peacekeepers.” Like its real-life counterpart, the bar is called Mike’s Place and is located in Jerusalem. For reasons not immediately apparent, Mike takes to the young man. He invites him to Jerusalem, gives him a job as a bartender, suggests ways to get to know Sasha—his own personal favorite—and pays her to be Mendy’s surprise “present.” It turns out that Mendy’s innocent face—and more importantly his Hassidic curls—are quite useful in Mike’s sideline business, which is smuggling dope. No one thinks to ask any questions when they see Mendy on the road. Hooked by Sasha and the crowd at Mike’s Place, Mendy tells his parents that he’s off to study at a yeshiva in Jerusalem, hoping that it will help him to get back his “spark” for religious training. “We’re so happy you can share your problems with us,” his father intones as his mother beams. “In Jerusalem you feel God everywhere, in every stone, in every glass of water.” They have to be the most clueless parents of an adolescent ever to appear on screen. Meanwhile, through an unconvincing twist of fate, Sasha decides to leave Tel Aviv for Jerusalem, where she ends up living with Mendy and Mike.

student masturbating in the bathroom of his parents’ house. It’s the complex networks of prostitution and porn. It’s the complicated relationship between the crazed nationalist settler—the Exterminator—and the black-hat yeshiva rabbi, who can barely stand to look at him when he walks into Mike’s Place to warn Mendy to shape up, ship out, and go back home. It’s the young boy who blows himself up on a bus. And it’s Razi, the only adult Arab character in the film, who is treacherous, traitorous, and a bit of a lecher. He’s the wheeler-dealer with a cell phone attached to his ear and a letter from the president in his pocket—which he must offer up when he’s interrogated at a checkpoint. Gorlin throws it all out there; now go figure what it means. A graduate of the University of Pennsylvania who once worked as a congressional intern, he’s coy on the subject of politics. “I don’t know if you see my politics in the film,” he told the Observer’s Helen Ivor-Smith. “I hope you don’t because it’s a coming-of-age story.”

The Holy Land doesn’t provide much in the way of brilliant insights into the Palestinian/Israeli conflict, nor does it really attempt an adequate depiction of the conflict. What Gorlin manages to do is show a slice of life in Jerusalem. There is wonderful cinematography and a few details that are perfect. The film is particularly good in its use of languages—English, Hebrew, Russian, Arabic, and an occasional blend of two languages in a single sentence. Whether anyone really communicates, however, is another question.

Throughout the film Gorlin runs into problems. In an effort to show us another side of Jerusalem, he ends up with too many caricatures and too many issues. Stein’s portrayal of Mike as the loudmouthed, know-it-all, former war correspondent is especially grating, like fingernails on a chalkboard. Moreover, Gorlin occasionally gets carried away with the Biblical symbolism. Sasha, for example, is not only Mary Magdalene. In one scene in a desert village, she turns into a contemporary Delilah with a pair of scissors.

What saves the film, what makes it worth watching, are the performances of Rehany and Semel as Mendy and Sasha. Semel has a wonderfully expressive face and is capable of adding dimension to a potentially stereotypical character with a single inflection. “I have busy, busy, busy, day in Tel Aviv,” she tells Mendy at one point, shaking her head and emphasizing “busy, busy, busy” as if she were an Old World grandmother preparing for a day at the market. Instead she is on her way to act in a particularly loathsome porn film to earn back the passport that her keeper has been holding hostage. Oren Rehany has the awkward goofiness of late blooming adolescence and the heavy burden of innocence down pat. You can’t help but watch him trip down the steps of Jerusalem with Sasha, looking so ordinary and carefree, and wish that brief moment could last forever.