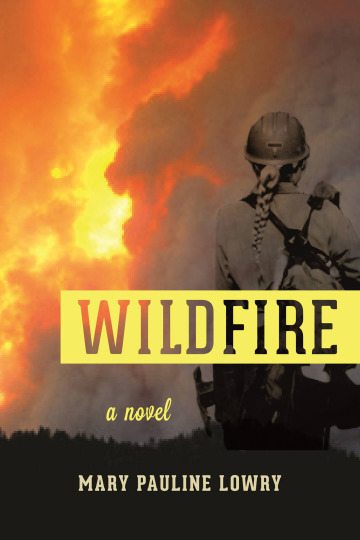

The Observer Review: Wildfire, by Mary Pauline Lowry

Mary Pauline Lowry’s two years battling wildfires in the American West fuel her debut novel, Wildfire, whose protagonist, Julie, joins an all-male wildland firefighting crew in Pike National Forest after flunking out of college. Julie’s radical career choice defies the high-society aspirations of the icy grandmother (aptly named Frosty) who raised Julie after her parents’ death in a car crash a decade or so earlier.

The novel opens and closes in Julie’s first season on the crew, but her troubled past weighs as heavily as the 40-pound pack she carries on deployments. Along with her Pulaski axe and emergency fire shelter, Julie hauls unresolved grief, the pain of Frosty’s cruelty and her own battle with bulimia—the latter a self-destructive proxy for the pyromania she developed as a teenager after her parents’ fiery death.

Julie arrives at the Pike Fire Center with virtually no experience combatting dangers so imminent or daunting. The novel is driven by her attempts to master the art of firefighting and her hunger for respect among a tribe of men who expect her to fail. She’s assigned to the digging crew, which cuts a fire line through the forest soil behind a pair of sawyers, who cut the trees, and swampers who clear away the debris that would otherwise feed the flames.

By Mary Pauline Lowry

Skyhorse Publishing

$24.95; 304 pages

The men who form the crew—who at first tease Julie mercilessly—are an assortment of masculine prototypes: the ruthless (and sexist) retired Navy SEAL; the pretty-boy rookie; the gentle brute who celebrates each and every “grumpy” he drops in the brush; and the expert veteran, whose purist love of firefighting is his life’s meaning. Julie faces all the adversity you’d expect—the struggles to keep up, to match the men’s strength and stamina, and to win the heart of the crew’s god-fearing hometown boy—all while trying to embrace the isolation and ferocity that such treacherous and grueling work entails.

Julie’s losses and triumphs put her through predictable paces, but city slickers will find the Pikers’ efforts compelling and edifying. It’s impossible to leave this novel without a deeper appreciation for the men and women we rarely see in news reports of drought and fire in the West.

But the novel’s action-packed momentum lags under the weight of some saccharine dialogue and emotions and realizations stated too baldly: “We sat together in silence for a long time, our longing for each other filling up the wide open night, burning like the orange glow on the hills around us.” Or, “Sam was right; sometimes nature has a mind of its own.”

Julie’s bulimia makes the story harder still to swallow (cheap pun intended). Her need to purge, while somewhat plausible, reads more like a prop than the earned result of Julie’s pain and longing. When she enters an eating contest with members from another crew, her condition is transformed from tragic to comic, stripped of its underlying psychological complexity.

Ultimately, Julie seeks courage, love and family, and Wildfire works well enough to make readers want it for her. She gains much of what she’s seeking, but too many parts of the novel feel flat and without nuance. Then again, in the world of firefighting, where a line through the forest can be a literal difference between life and death, perhaps there’s little room for subtlety.

Wildfire is likely headed for the cinema, having been optioned by producers Bill Mechanic (Coraline, Fight Club and Titanic) and Suzanne Warren. Lowry, who grew up in Austin and earned an MA in English from the University of Texas, is writing the screenplay, which should deliver the narrative in a more suitable format, where raging fires, the crew’s loving antagonism and Julie’s residual wounds may play better than they do on the page.