Whistleblower, Landowners: TransCanada is Botching the Job on Keystone XL Pipeline

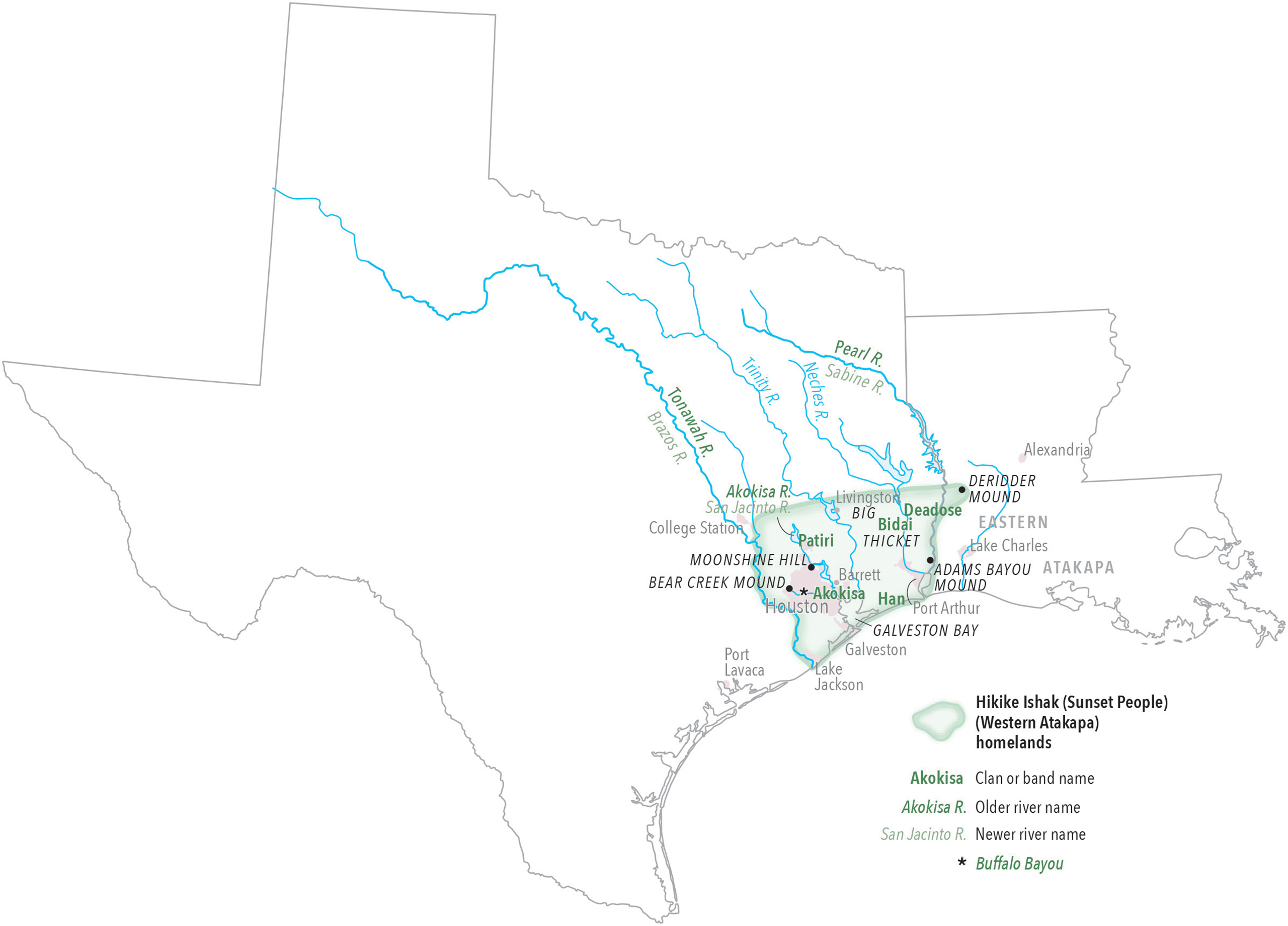

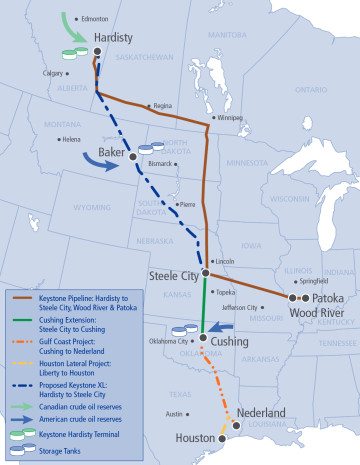

On a Wednesday in late June, Evan Vokes packed his only pair of shorts in a suitcase and boarded a plane to Dallas, happy to trade the chill of Calgary, Canada, for a Texas summer. Over the next four days, he’d travel by car and a low-flying Cessna from Paris south to Beaumont, following the route of the Keystone XL pipeline, slated to bring oil from the Canadian tar sands to refineries on the Gulf Coast. Armed with an encyclopedic knowledge of arcane pipeline regulations, Vokes came to check out claims from landowners that his former employer—Canadian company TransCanada—was botching the job on the pipeline.

For five years, Vokes had inspected TransCanada projects across North America and, too often for his liking, found they were poorly constructed and didn’t meet engineering codes. He’d tried to get his superiors to address the problems, to no avail, and was fired last year. In East Texas, he found that TransCanada hadn’t changed its way—even on what may be the most controversial pipeline ever proposed for North America.

“I believe in building pipelines,” he says. “But I like to have what’s in the pipeline [stay] inside the pipeline.”

TransCanada has long contended that Keystone XL will be the safest pipeline ever built. But in East Texas, landowners are growing increasingly alarmed by what they’ve seen first-hand: multiple repairs on pipeline sections with dents, faulty welds and other anomalies. The Oklahoma-to-Texas segment of Keystone XL is 90 percent complete, according to the company, and is expected to come online later this year.

Vokes says TransCanada prioritizes staying on schedule over quality. In a 28-page complaint filed last year with the Canadian government’s pipeline regulator, he describes rampant code violations on other TransCanada projects. He claims that the repair work in Texas proves the company is still ignoring the engineering codes and regulations that guide pipeline construction and warns that Keystone XL will likely leak.

“Now if they were actually following this,” he says, holding up a section of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers’ code governing liquid hydrocarbon pipelines, “they wouldn’t have this,” he says, pointing to an array of photos documenting problems with the pipeline.

In one of the photos, David Whitley—who owns 88 acres along the pipeline route near Winnsboro—stands in front of a cut-out piece of pipeline on his property. The words “dent cut out” are spray painted in red against the blue-green steel. Other landowners have seen similar cutouts or stakes in the ground with the words “anomaly” or “weld” written in Sharpie.

Rita Beving of Public Citizen says she and Whitley approached an independent inspector working on Keystone XL in late May, who told them there were dozens of “anomalies,” or flaws, in the 60-mile stretch between the Sulphur and Sabine rivers. Beving and Vokes later flew the pipeline route from southeast of Tyler to Corrigan (about 25 miles south of Lufkin) and say they saw dozens of areas with exposed pipe, pipe cutouts and freshly reburied line.

TransCanada says it follows regulations and engineering codes and is only making repairs to build a quality line. “It makes absolutely no sense to cut corners or to build a sub-standard pipeline to save a few dollars,” Howard says. When asked how many anomalies the company is repairing, he said it is replacing nine 9-foot sections on 80 miles of tested pipeline “out of an abundance of caution.”

“That simply isn’t true,” says Beving, who has flown over and driven along parts of the route several times. “All these anomalies call into question the kind of quality that is being built into this pipeline.”

Once it concluded construction in East Texas, TransCanada ran a series of required tests on the pipeline, including a test where water is pumped through pipe at high pressure. The tests revealed some imperfections that spokesperson Shawn Howard says were created when the pipeline was buried.

When workers excavated pipeline on Whitley’s land, he discovered one end of the pipe laying on top of a huge red rock. He took photos of the trench and later returned to find the piece of pipe marked “dent cut out” just feet from where the rock and pipeline were now reburied. Vokes says it’s hard to dent thick steel pipe, but that pressing the pipe’s massive weight against a hard surface like a rock will do the trick.

Dr. Mohammad Najafi, a construction expert and civil engineering professor at UT-Arlington, reviewed Whitley’s photos and says landowners should be concerned. If the workers didn’t correctly “backfill” the trench and compact the soil the pipe would not be evenly supported and could sag. The dents and sagging could damage the pipe’s coating, leading to corrosion. Corrosion eventually creates holes, which can cause leaks. Leaks make holes expand and can ultimately result in ruptures.

Vokes says these problems suggest a qualified inspector wasn’t present during construction, as required by code. He and Najafi agree that a qualified inspector would have ensured there was adequate padding between the pipe and rock and wouldn’t have allowed improper backfilling. Asked how many inspectors it hired on Keystone XL, TransCanada gave no reply but said it hired hundreds of inspectors on Keystone I.

Landowners in Texas are worried that the frequency of repairs on Keystone XL suggests there are more problems in the pipeline that haven’t been detected. They also worry about new welds; each time a piece of pipe is replaced, two new welds are needed to attach the new section to the pipeline. Because hydrotesting is required only once, these welds are never pressure-tested like the rest of the welds on the line. “I’m a little bit concerned about a leak or something now that they have cut into it and repaired it so many places,” Whitley says.

Many remain skeptical about the future safety of a pipeline that’s slated to transport diluted bitumen (“dilbit”). When the tar-like bitumen is extracted from Canada’s oil sands region, it has to be diluted using natural gas liquids that include benzene (a known carcinogen) and other chemicals. Environmentalists warn of the fuel’s carbon footprint, but fear of another dilbit spill has been more of a factor in mobilizing conservative landowners against the pipeline. The oil industry insists that dilbit is comparable to conventional crude, but watchdog groups disagree and recent spills have helped discredit that claim.

Growing opposition to Keystone XL has culminated in widespread acts of civil disobedience, including huge sit-ins outside the White House. Environmentalists believe this resistance has helped stall approval of the full Keystone XL project, which would run from Alberta to Port Arthur and requires a presidential permit to cross the international border. Last year, President Barack Obama rejected TransCanada’s application but encouraged it to reapply and expedited permitting for the “southern leg.” When completed, this southern leg will link the company’s existing Keystone I pipeline – from Alberta to Oklahoma – to ports on the Gulf Coast. If approved, Keystone XL will create another line from Alberta to Oklahoma, more than doubling the volume of oil sands crude flowing into Texas.

In 2010, the U.S. Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) sent TransCanada a warning letter citing a need for improvement in the company’s quality assurance program on the natural gas line Bison.

Bison exploded in Wyoming four months later, just six months into operation. TransCanada had previously touted the pipeline’s safety, assuring the public that it had to adhere to especially stringent standards and close PHMSA oversight during construction.

But emails showing that TransCanada knew about serious problems on Bison surfaced in the aftermath of the explosion. In his written complaint to Canada’s National Energy Board, Vokes described inadequate inspections on Bison and numerous violations on other projects. The board later verified many of Vokes’ allegations and announced it would review TransCanada’s inspections and integrity management programs.

Keystone XL opponents say the Bison explosion and the 12 leaks on Keystone I during its first year of operation prove that TransCanada has a poor safety record and routinely underestimates risks. TransCanada predicted Keystone would leak just once in seven years and that Bison wouldn’t need to be repaired for decades after it was built.

A spill on Keystone XL could be devastating. In July 2010, a pipeline owned by Canadian energy company Enbridge leaked 843,000 gallons of dilbit into the Kalamazoo River in Michigan. The exterior coating of the pipe corroded, which eventually led to a crack and rupture. Three years later, cleanup crews still haven’t extracted all the fuel from the river because unlike oil, which floats on top of water, the dense bitumen sinks after the natural gas liquids evaporate, making it harder to clean up.

In March, ExxonMobil’s Pegasus line, also carrying dilbit, leaked and spilled more than 200,000 gallons in Mayflower, Arkansas. The dilbit seeped up from the ground in a residential neighborhood and 22 homes were evacuated. Residents are still experiencing nausea, rashes and breathing problems.

In East Texas, landowners hope they won’t suffer a similar fate. “I’m going to be wondering whether there’s a leak,” Whitley says. “It could be an environmental disaster.”