Visiting the LBJ Library in the Shadow of Selma

A version of this story ran in the February 2015 issue.

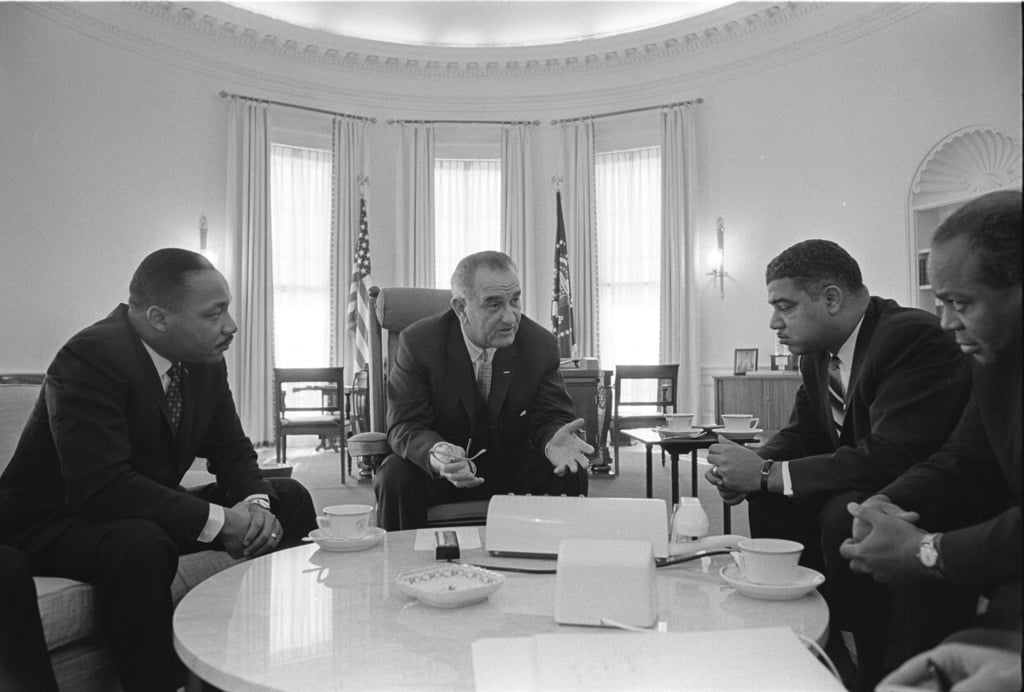

Above: President Lyndon B. Johnson meets with civil rights leaders Martin Luther King Jr., Whitney Young and James Farmer in the Oval Office in 1964.

On the top floor of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum in Austin, visitors can shuffle through a precise replica of Johnson’s mid-1960s Oval Office, complete with actual furniture used by the former president. For those who have recently watched the Oscar-contending film Selma, which follows Martin Luther King Jr. through a series of pivotal 1965 marches that helped win public support for the Voting Rights Act, the room will look familiar. The film’s designers did an admirable job recreating Johnson’s White House. It’s possible they even visited the Austin museum for research. The screenwriters, however, were less diligent.

The events of the film stray far from the historical record, which record it is the LBJ Library’s mission to preserve. One heated Oval Office scene has Johnson informing King that he won’t introduce a voting rights bill to Congress because it would interfere with the president’s domestic priority, the War on Poverty. After the meeting, Johnson and J. Edgar Hoover seem to discuss the idea of assassinating King. It’s implied that Johnson declines only because he’s afraid that Malcolm X will assume leadership of the civil rights movement in King’s absence. Later, enraged by King’s insistence on marching through Selma, Johnson instructs Hoover to send audio tapes of one of King’s extramarital affairs to King’s wife, Coretta, hoping to destabilize the movement.

Hollywood has tended to find LBJ’s craggy face and Southern accent more useful as the traits of a villain than of a hero—even when dramatizing domestic victories like the Voting Rights Act, where Johnson’s progressive leadership is undeniable.

In fact, as LBJ Library Director Mark Updegrove has written convincingly since the film’s release, the historical Johnson and King were allies on civil rights, and were both indispensible to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Johnson supported King’s strategy of exploiting incidents of oppression of black would-be voters to help convince members of Congress to pass meaningful legislation. The LBJ Library houses tape of Johnson advising King in January 1965 to “find the worst condition that you run into in Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana or South Carolina … and get it on radio, get it on television, get it in the pulpits, get it in the meetings, get it every place you can; pretty soon, the fellow that didn’t do anything but drive a tractor will say, ‘That’s not right, that’s not fair.’ And then, that’ll help us in what we’re going to shove through in the end.”

Eyewitnesses and historians have come forward to support Updegrove’s critique of the film. Former Atlanta mayor, congressman and United Nations ambassador Andrew Young was present at the meeting between King and Johnson depicted in the film. “It was not very tense at all. We were very much welcomed by President Johnson,” Young told The Washington Post recently. “He and Martin never had that kind of confrontation.”

As for the tape of King’s affair: “If the movie suggests LBJ had anything to do with the tape, that’s truly vile and a real historical crime against LBJ,” Pulitzer-winning MLK biographer David Garrow told The New York Times. In the same article, Diane Whorton, another Pulitzer-winning historian of the civil rights movement, summed up her reaction to the film’s depiction of Johnson: “I kept thinking, ‘Not only is this not true, it’s the opposite of the truth.’”

For those who follow the headlines, the outcry over Selma’s historical inaccuracies may feel like old news. It has been covered in national and local media as the film has slowly widened its release. The reaction began with Updegrove’s op-ed in Politico on Dec. 22. Former Johnson staffer Joseph Califano Jr. chimed in with an op-ed four days later in The Washington Post. Within a week, the Post and Times had delivered in-depth reporting on the issue. Before long, it was on everyone’s radar.

Historical inaccuracy in Hollywood films is as old as The Birth of a Nation and Gone With the Wind. What’s salient about the Selma criticism is that it has stuck. How that happened—and the role played by the LBJ Library and its supporting organization the LBJ Foundation—sheds light not just on our changing appreciation for one of the most maligned American presidents, but also on how vital passages of our history are written, rewritten and adjudicated in the public sphere.

In Austin’s Oval Office recreation, behind the desk where so many bills were signed, there’s a locked door leading to an apartment off-limits to museum-goers. I’m in that inner sanctum, designed by Johnson and his wife, Lady Bird, for working and entertaining guests during his post-presidency career. Since Johnson’s death in 1973, the suite has been stuck in a time warp: groovy lime-green carpet in the bathroom off the office, puke-yellow upholstered Brady Bunch chairs around a conference table in the main room. A painting given to Johnson by Pope Paul VI hangs alongside a panel screen given to his daughter, Lucy, as a wedding gift by Chinese leader Chiang Kai-Shek.

When Updegrove enters with Anne Wheeler, head of publicity for the LBJ Library, I’m staring at a coffee table inlaid with 25 pens. Each one was used to sign a landmark bill or executive order. I point and say something about the breadth of Johnson’s legislative accomplishments, how it’s scarcely imaginable in the modern era of Washington gridlock.

Updegrove blinks, confused. “Oh,” says Wheeler, realizing I haven’t looked closely enough at the table. “You know those pens are just from the education bills.”

“Speaking broadly, 1965 is the most remarkable legislative year of the 20th century, with the possible exception of 1933, the first year of the New Deal,” Updegrove tells me. Now we’re sitting on a sofa almost as old-fashioned and stiff-backed as the ideals set forth in Johnson’s January 1965 State of the Union address, delivered 50 years ago last month: “The Great Society asks not how much, but how good; not only how to create wealth, but how to use it; not only how fast we are going, but where we are headed.”

Such sentiments are often echoed by Democratic politicians, but Updegrove wants to talk about how much Johnson actually accomplished in keeping with those ideals. “LBJ wanted to do the greatest good for the greatest number. That’s not an expression you hear a lot anymore,” he says. “And if you measure LBJ’s legacy in those terms, he’s one of the greatest presidents we’ve ever had.”

Speaking broadly, 1965 is the most remarkable legislative year of the 20th century, with the possible exception of 1933, the first year of the New Deal.

That opinion is not widely held. Conservatives such as Wisconsin Congressman Paul Ryan have taken the 50th anniversary of the War on Poverty as an opportunity to criticize and attempt to dismantle the social safety net that Johnson envisioned and built. Generations of Democratic politicians have run from Johnson’s legacy and the taint it acquired from the Vietnam War. (In 1992, candidate Bill Clinton visited the LBJ Library but did not speak the ex-president’s name or recognize Lady Bird, who was present on the stage where Clinton spoke.) And Hollywood has tended to find LBJ’s craggy face and Southern accent more useful as the traits of a villain than of a hero—even when dramatizing domestic victories like the Voting Rights Act, where Johnson’s progressive leadership is undeniable.

Speaking up for Johnson against such headwinds can be a lonely battle, and Updegrove sometimes seems self-conscious about his position. “I would characterize our role not as defending the legacy but as explaining the era and offering material for people to learn more themselves,” he tells me. “I happen to believe as a historian that Lyndon Johnson is one of our great and underrated presidents. But I don’t feel any responsibility to defend his legacy in my role as the director of the LBJ Library.”

As for his Selma editorial, he says, “Many people, young folks in particular, get their history from popular culture, and they believe that there’s some sort of standard in place for those movies based on history, to ensure that it’s depicted responsibly and accurately. So I felt the need to speak out and set the record straight.”

“Presidential libraries find themselves sometimes caught between two schools,” explains H.W. Brands, a historian at the University of Texas at Austin and author of several books about American presidents. “One is, they’re the neutral arbiter of the historical record. Wearing that hat, library directors have really no stake in what the story is. But on the other hand, if you’re running a group called Friends of the LBJ Library, then it behooves you to make LBJ seem like someone you’d want to be friends with.” Indeed, Amy Barbee, the LBJ Foundation president, tells me that she discussed the Politico editorial with Updegrove ahead of its publication, saying, “We work together on the legacy issues.”

Still, says Brands, “Of all the libraries I’ve worked with, and I think I’ve worked with just about all of them, LBJ handles this as well or better than any other. LBJ is really a model of openness to researchers to come in and see what the record is and tell the story however you like it. And at the same time it tries to make it accessible to people who are not professional historians.”

The LBJ Library perhaps has more misconceptions to correct than the average presidential library. Long before Selma, Oliver Stone’s JFK suggested to a generation of filmgoers that Johnson was involved in his predecessor’s assassination. (“Nothing that I have found in my research” implicates him, Pulitzer-winning Johnson biographer Robert Caro has written.)

By several accounts, the custodians of Johnson’s legacy had not been planning to spend the first months of 2015 defending the former president from historical misrepresentations such as those made in Selma. Instead, as The New York Times reported last year, Johnson’s heirs and supporters were engaged in “one last campaign” to rehabilitate the ex-president’s tarnished legacy. They planned to focus in particular on the anniversaries of his myriad legislative accomplishments of 1965.

Their case, which Updegrove pitches to me in the presidential suite, is compelling. Johnson’s policy-enacting efficiency as president is legendary, but 1965 stands alone as an annus mirabilis for socially progressive legislation. Even a heavily abridged recounting of the year reads like a Book of Genesis of American social democracy.

In January 1965, Johnson was inaugurated into his first full term as president with supermajorities in both houses and a landslide electoral victory at his back. In April he signed the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, which established the federal government’s role in funding disadvantaged schools and students. The law remains on the books to this day, amended, beaten, bloodied, and renamed as the No Child Left Behind Act. In July, Johnson and Congress raised Social Security payments, immediately lifting 2.5 million seniors out of poverty, and created Medicare and Medicaid. In August, the Voting Rights Act finally assured African Americans of access to the ballot box. In 1965, 6.7 percent of African Americans in Mississippi were registered to vote. By 1967, that number would rise to 59.8 percent.

“There’s not a single president who wouldn’t stake his entire domestic reputation on just one of those bills,” Updegrove says. But Johnson was just getting started.

The genius of Johnson’s Great Society was to wed the civil rights revolution to New Deal liberalism. In 1965, those ideals marched hand in hand. Selma captures none of that unity.

Over the next two months he created the Department of Housing and Urban Development and the National Endowment for the Arts. In October he signed the Immigration and Nationality Act, which dispensed with a racial quota system that had favored immigration from Western- and Northern-European countries and had barred entry for most Asian and African immigrants; this act opened the door to the vibrantly multicultural society that Americans now take for granted. In November came the Higher Education Act, which remains the primary public mechanism for helping lower-income Americans pay for college. Johnson’s 1965 successes also included a major farm bill, legislation protecting clean air and creating new national parks, an executive order mandating affirmative action for government contractors, and a highway-beautification bill that permanently transformed America’s roadways.

Reading over the list, a modern-day liberal can’t help salivating. What might 2009 have been if Barack Obama had attacked his window of supermajority opportunity with the same gusto and arm-twisting savvy? We might have half a dozen progressive accomplishments on the scale of the Affordable Care Act.

Johnson’s legacy, of course, carries a major caveat, and 1965 contains a much less laudable set of milestones. At the start of the year, there were no U.S. combat troops in Vietnam. In March, Johnson launched the ground war with a small force of Marines. By the end of the year, combat troops totaled more than 200,000. Any estimation of Johnson’s record regarding “the greatest good for the greatest number” must reckon with the 60,000 Americans killed and the 300,000 maimed in that misguided war.

Many presidential historians, Updegrove included, see Vietnam as the primary reason that LBJ’s domestic legacy has been so consistently overlooked and underrated. Author and radio commentator Sarah Vowell, who has written about presidential libraries, has an additional take. “His most famous speech is about not seeking reelection,” Vowell tells me in an email. “He’s not an inspiring figure. His greatness—his political mind, the way he worked behind closed doors to talk Congressmen into doing his bidding—is probably too back room, too blatantly political, to capture our imaginations. Look at the current president. I think history will generally be kind to him because there’s so much good tape of him talking. But he has none of LBJ’s offstage talents at squeezing the legislative branch. Effective but distasteful isn’t the sort of legacy that sells tickets.

“Even after Watergate and Iran-Contra and the Clinton impeachment, Americans still want to think of the president as a role model,” Vowell adds. “Which is insane.”

It’s worth mentioning that Johnson’s “distasteful” political biography includes stealing a Senate election in Texas in 1948, according to Caro. Still, both the Vietnam War and power-hungry Johnson himself have been history for more than 40 years. Medicare, Medicaid, the Voting Rights Act, Pell grants, the NEA, and our multi-cultural immigration system live on. Right?

That’s the problem, defenders of the Johnson legacy argue. Without an ongoing appreciation for the Great Society vision that united these signature achievements, they’ve been subject to piecemeal attacks and weakening modifications over the years. In 2013, for example, the Republican-controlled Supreme Court gutted Section IV of the Voting Rights Act, which protects voters in historically segregationist areas, including swaths of Texas. President George W. Bush wagered the political capital of his 2004 presidential victory on an unsuccessful push to privatize Medicare. As noted above, Johnson’s Elementary and Secondary Education Act has been altered beyond recognition by testing-happy reformers, and efforts are underway to divert its funding mechanisms toward private charter schools.

“It’s important to look historically at what has been achieved, to highlight how far we’ve come in 50 years due to these laws that were passed,” says Barbee, the LBJ Foundation’s director. “Medicare and the Voting Rights Act are part of the fabric of American life. It’s frightening to think that these laws have been weakened somewhat.”

Barbee and Updegrove have been central to efforts to promote appreciation for the historic and modern-day significance of such laws, and of the Great Society and War on Poverty in general. Last year, the LBJ Library hosted a summit on the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Four American presidents—Carter, Clinton, George W. Bush and Obama—took the stage to praise the bill, which effectively ended Jim Crow. This year, the LBJ Foundation will support a conference to examine the history and future of Medicare and a concert to celebrate the legacy of the National Endowment of the Arts. Both events will be held in Washington, D.C., within earshot of the halls of power.

Vowell argues that the museum components of presidential libraries can also play an important role in helping ordinary people grasp the importance of a complex legacy like Johnson’s. “I do think empathy can be educational,” she tells me.“Trying to see anything, including historical events, from the perspective of those who lived them, is an important component of piecing together what happened.

“I remember in the Johnson library there are display cases about the president’s work as a teacher among impoverished Mexican-American children,” she adds. “I seem to recall a letter from one of his students. Just seeing the pictures explained a thing or two about how weird it was that a Texan who looked and talked like a good old boy made such progress on poverty and civil rights.”

Pressed by interviewers, Selma director Ava DuVernay has taken several tacks in defense of her film, including denying that her Johnson is a villain, impugning Johnson’s reputation generally (telling NPR host Terry Gross, “If I had wanted to paint someone as a villain, particularly LBJ, there’s a lot I could do in that regard”), and defending her right to tell “the truth, not the facts.” Of course, it would be unfair to imagine Selma as the product of a single creator. Though she has indicated that she rewrote the movie’s screenplay, DuVernay is not credited as Selma’s screenwriter, and she signed on to the project after an early draft had been written and the film had been partially cast. Selma is a commercial dramatization of history, aimed first at attracting investors, and, later, at selling tickets. In the process of its creation, one or more people decided that a fictitiously villainous Johnson would sell better than the historical Johnson.

It does contemporary politics no favors to paint the epochal year of 1965 as one of conflict between an anti-poverty agenda and the civil rights movement, when neither King nor Johnson would have seen it that way.

The reasons for that are complex and have been addressed above. But even aside from questions of one man’s legacy, it does contemporary politics no favors to paint the epochal year of 1965 as one of conflict between an anti-poverty agenda and the civil rights movement, when neither King nor Johnson would have seen it that way.

“It was about leveling the playing field,” Updegrove says. “Medicare is not just about health care. It was a poverty bill. When it was passed, over a third of Americans over 65 lived in poverty. They were unable to afford medical care in their older age and were essentially put out to pasture.” Likewise, he says, “The Elementary and Secondary Education Act, as LBJ told Martin Luther King, was one of the most potent civil rights acts you could put on the books.” Indeed, the LBJ Library houses tape of Johnson and King discussing the bill’s transformative implications for poorly funded black and mostly black schools across the country.

The genius of Johnson’s Great Society was to wed the civil rights revolution to New Deal liberalism. In 1965, those ideals marched hand in hand. Selma captures none of that unity, but it does reflect a modern split on the left, where identity politics are often divorced from the issue of economic inequality, and historically marginalized groups are instead assuaged with better representation in the media and in the upper ranks of institutional power.

Along those lines, DuVernay, too, deserves to be regarded as a sympathetic figure in the story of Selma. She is historically significant as the first black female director of a major Oscar-contending film. That job entails skillfully directing the script her producers signed off on and quarterbacking an unapologetic Oscar campaign. DuVernay has succeeded in both tasks, perhaps even in the mold of the historical Johnson—as a savvy political operator with her eyes on the prize of long-lasting institutional change.

Perhaps it was never DuVernay’s job to sincerely consider the presidential history her movie depicts. That task falls to critics, historians and audiences. And thanks in part to Updegrove and Califano, the system has worked: All but the lowest-information moviegoers are now likely aware that Selma’s depiction of Johnson is problematic.

Looking ahead to other upcoming anniversaries of major legislation, Updegrove is ready to move on from the Selma controversy. He has other historical fish to fry. For instance, Ronald Reagan’s old line: “We had a war on poverty, and poverty won.”

“If you look at the statistics, that’s not true,” Updegrove tells me, leaning forward on the sofa and speaking excitedly. “The poverty rate before the War on Poverty was waged was about 20 percent. And after LBJ left office, that number fell to 13 percent. That’s the largest one-time reduction in our history. That is staggering.”

The poverty rate before the War on Poverty was waged was about 20 percent. And after LBJ left office, that number fell to 13 percent. That’s the largest one-time reduction in our history.

In 1968, that 13 percent poverty rate was the lowest America had ever seen. Since then, it’s been a reliable average, with minor fluctuations in either direction, except during the recent financial crisis, when it ballooned again to pre-1966 levels. It might have stuck there, too, if proposed Republican austerity measures had found political traction.

Instead, we happen to have a president in the White House who respects Johnson’s legacy—the first, in fact to visit the LBJ Library as a sitting president and praise that legacy. (No small coup for Updegrove, that.) At last year’s Civil Rights Summit, hosted by the LBJ Library, Barack Obama answered Reagan head on:

“Yes, it’s true that, despite laws like the Civil Rights Act, and the Voting Rights Act and Medicare, our society is still racked with division and poverty. …[I]t’s perhaps easy to conclude that there are limits to change; that we are trapped by our own history; and politics is a fool’s errand, and we’d be better off if we roll back big chunks of LBJ’s legacy…

“I reject such thinking. Not just because Medicare and Medicaid have lifted millions from suffering; not just because the poverty rate in this nation would be far worse without food stamps and Head Start and all the Great Society programs that survive to this day.I reject such cynicism because I have lived out the promise of LBJ’s efforts. … Because I and millions of my generation were in a position to take the baton that he handed to us.”

Reagan’s take on Johnson’s legacy was just as wrong as Selma’s, or maybe worse, considering the damage his misreading may still cause. Here’s hoping that in 2015, Obama’s response to Reagan—and Updegrove’s response to Selma—is a correction that sticks.