United Nations: Children Crossing the Border Qualify for Asylum

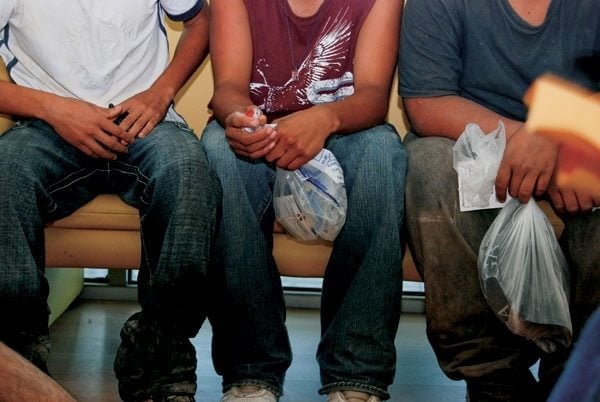

Above: Unaccompanied children waiting in a Mexican social service office

A majority of the unaccompanied Mexican and Central American children crossing the U.S.-Mexico border should qualify for political asylum, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees’ office, which released a report Wednesday on the growing humanitarian crisis.

“There is an alarming number of children seeking asylum. The U.S. government estimates this year there could be as many as 60,000 children in federal custody,” said Leslie Velez, a lead author of the new UNHCR report “Children on the Run,” released by the agency’s Washington, D.C., office, which covers the United States and the Caribbean.

Velez, in a conference call with reporters, said the “surge” of children crossing the U.S.-Mexico border without a parent or adult guardian began in 2011, and mirrors a sharp increase of adult U.S. asylum claims from El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico that rose from 5,369 in 2009 to 36,174 in 2013. The growing humanitarian crisis is also affecting countries besides the United States. Neighboring Central American countries like Costa Rica and Nicaragua have seen a 432 percent increase in asylum claims, according to the report.

The number of U.S. immigration apprehensions of unaccompanied children from Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras has risen sharply from 4,059 in 2011 to 21,537 in 2013, and the majority of them cross the Texas-Mexico border in the Rio Grande Valley, the shortest route from Central America into the U.S. Local and state authorities and advocates have struggled to provide resources and beds for all of the children arriving in Texas. In 2012, children were briefly sent to Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio to be housed in dormitories until additional shelters could be found.

The agency also interviewed unaccompanied minors from Mexico, and found that the number of Mexican children apprehended has also increased from 13,000 in 2011 to 18,754 in 2013. As I reported in the 2010 Observer story “Children of the Exodus,” Mexican children traveling alone are treated differently by U.S. immigration officials than Central American children. Instead of being screened and interviewed by U.S. Border Patrol agents, to see whether they qualify for asylum—as required by a congressional mandate—children are often returned to the nearest Mexican border city within 24 hours.

Velez said it was the U.N.’s task to document the reasons children are fleeing their homes in an unprecedented number. Velez said the agency interviewed 404 children from the four countries and found that pervasive violence and the inability of the state to provide security for its citizens were primary reasons for fleeing their countries. “At least 83 percent of the children had more than one reason for leaving,” she said.

The study’s authors said 72 percent of the children they interviewed from El Salvador qualified for “international protection,” (meaning possible asylum), the highest rate of any country. Children cited organized crime and gang violence as their primary reasons for fleeing El Salvador.

At least 48 percent of the Guatemalan children interviewed were indigenous, and they cited deprivation (poverty), violence at home and in society as their main reasons for leaving the country. At least 38 percent of Guatemalan children “raised international protection concerns,” according to the UNHRC.

Children from Honduras, like El Salvador, cited organized crime and pervasive violence in their country as primary reasons for leaving, and at least 57 percent of them raised international protection concerns, according to the report.

Findings from interviews with Mexican children were especially striking, according to the report. At least 64 percent of the children interviewed raised “international protection” concerns. And at least 38 percent of the children said they had been recruited by organized crime to be used in human trafficking “precisely because of their age and vulnerability,” according to the report. As I wrote in 2010 in “Children of the Exodus,” Mexican children are often used by organized crime for everything from drug smuggling to guiding immigrants through U.S. ranch lands, because if they are arrested they will be deported immediately back to Mexico. These children are powerless to defend themselves and often are intimidated and forced to participate in criminal activity.

In the report, the UNHCR asks that Central American countries, Mexico and the United States acknowledge that violence and insecurity are fueling the displacement of thousands of children and creating the humanitarian crisis. To help these displaced children, the agency recommends better asylum screening, and new or stronger laws to protect unaccompanied children.