The Shadow of the Son

The trials of the border's most powerful law-enforcement family

A version of this story ran in the April 2013 issue.

On a sweltering July afternoon in South Texas, Jose Perez found himself handcuffed in the front seat of a white Chevy Tahoe making his amends with God. His wife, also handcuffed, sat in the back seat, stricken with fear.

Six armed men had just ransacked their home, turning over furniture and busting open cabinets, while another man pointed an assault rifle at their faces. The men wanted drugs. After finding nothing, they forced the 62-year-old Perez and his 59-year-old wife into the SUV. A man in a black Kevlar vest got behind the wheel, shouting obscenities and orders at the other men. He seemed like a man possessed, pulling at his hair and sweating profusely. He said they were cops from the Hidalgo County Police Department. But Perez knew no such agency existed, and he was terrified. These couldn’t be cops.

“Call someone that sells drugs or else,” the man told Perez. “If you don’t call someone right away, I’m going to take you somewhere, and you know what I’m talking about.”

Perez didn’t need to hear details. Across the river, a cartel war over territory and money had been raging for more than three years. The driver, who couldn’t have been much older than 25, took off Perez’s handcuffs. The elderly man pulled out his cell phone and began dialing. A few minutes later, they pulled into the parking lot next to Matt’s Cash and Carry in Pharr. They watched as a gray Monte Carlo pulled up. In the trunk, the driver, whom Perez had just phoned, had two kilos of cocaine worth $50,000. The man in the bulletproof vest told Perez and his wife to get out of the SUV and not look back. “Don’t use your cell phone. Someone will be keeping an eye on you,” he warned. As they walked toward the expressway, they felt lucky to have survived.

The next morning, Perez couldn’t get over his anger. He wanted justice. But he was terrified to call the police. What if the men really were cops? Perez called his attorney, who advised him to contact the FBI. The FBI told him he’d have to file a report with the police. So Perez reluctantly phoned the local Pharr police station. Oddly enough, he testified later in a sworn affidavit, the men had stolen eight bottles of cologne and lotion. The unopened gifts had been Christmas presents from his kids. They’d also taken valuable jewelry, including a gold medallion of San Judas Tadeo and his wife’s gold-and-diamond bracelet, as well as $4,000 Perez had hidden in a dresser drawer. The men had trashed his place. The home invasion had been brazen, carried out in the middle of the day in a busy neighborhood in Pharr, and it had been sloppily executed. Later while surveying the damage, Perez’s wife found a 9mm Luger under a pile of clothes.

Perez and his wife recounted the bizarre, frightening robbery and kidnapping to a sympathetic female officer at the police station. A security camera in Perez’s home had recorded the entire incident, he told her. Two internal affairs officers from the Hidalgo County Sheriff’s Department arrived and asked to see the video. As the video rolled and the armed men came into the camera’s view, the color drained from the officers’ faces. “I know who that is,” one of them said. “That’s Jonathan Treviño. The sheriff’s son.”

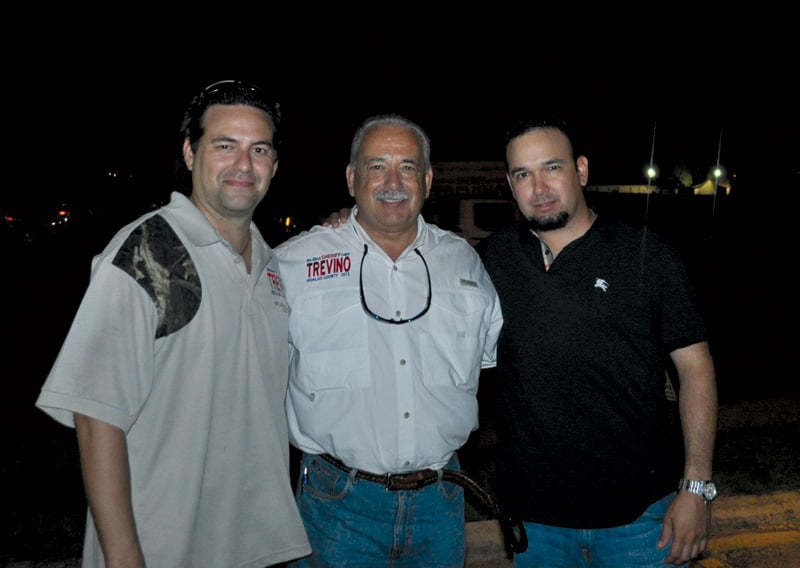

The sheriff of Hidalgo County was Guadalupe “Lupe” Treviño. The only things more important to the 64-year-old sheriff than his legacy as one of the most powerful law enforcement figures in South Texas were his three sons, especially his youngest, Jonathan, whom he was grooming to follow in his footsteps. The sheriff had engineered Jonathan’s quick rise in law enforcement. He made sure that Jonathan was appointed head of his own narcotics task force in late 2006—an unheard of assignment for a 22-year-old rookie fresh out of the academy. The six officers associated with the task force were Jonathan’s close friends, including Alexis Espinoza, who had his own family legacy to fulfill as the son of Hidalgo Police Chief Rudy Espinoza. They called themselves the Panama Unit.

Perez and his wife had just stumbled upon one of Hidalgo County’s worst-kept secrets—at least among the county’s drug dealers and law enforcement. The Panama Unit had been brazenly ripping off local drug dealers for at least six years, according to multiple law-enforcement sources. (Perez denies that he’s a drug dealer and says the unit targeted him by mistake.) Perez’s complaints sparked an FBI investigation that would lead to federal indictments of Jonathan Treviño and three other members of the Panama Unit. They were indicted after being caught in stings led by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and the FBI. Four of the Panama Unit members had been escorting kilos of cocaine across the county in marked Mission Police Department vehicles in exchange for thousands of dollars in bribes, according to a federal indictment. The feds recently issued a superseding indictment that charges all seven members of the Panama Unit with “conspiring to possess with intent to distribute” cocaine, marijuana and methamphetamine. The indictment also included two members of a drug-trafficking ring who conspired with the rogue cops to rip off other local traffickers.

Perez didn’t realize it at the time, but his call to the FBI would start to unravel allegations of cronyism and corruption within the county sheriff’s department. Current and former deputies told the Observer that the Panama Unit scandal is just the beginning. They described a sheriff’s department thrown into turmoil by the federal investigation. Many of the deputies the Observer spoke with expect more indictments. In Hidalgo County’s long, tangled history with the drug trade, residents have seen more than a few corrupt cops paraded before the news cameras. But many people in Hidalgo County are speculating that this investigation could implicate the county’s top law enforcement official and one of the most powerful politicians in the Rio Grande Valley—Sheriff Lupe Treviño.

The County’s Top Cop

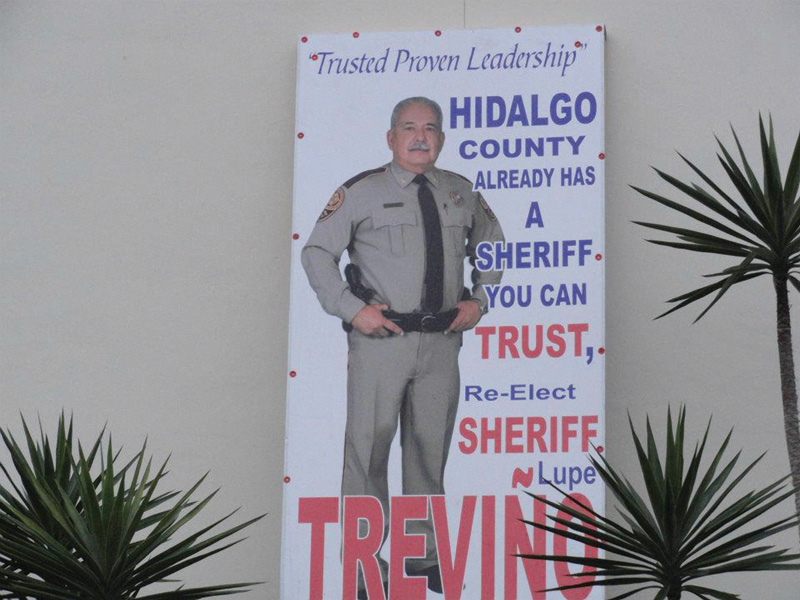

Lupe Treviño is an ambitious politician who relishes his role as a public figure. Since taking office in 2005 he’s kept up a schedule of weekly appearances. Despite overseeing one of the largest law-enforcement agencies on the U.S.-Mexico border, with 763 employees and a $44 million budget, he rarely turned down an event. On his Facebook page there are hundreds of photos from community events. In one photo, he holds a pair of giant scissors, standing next to a life-sized Elmo and Sgt. McGruff as they celebrate the opening of a Head Start program. In another he poses at a nursing home next to the “king and queen” of a Valentine’s Day pageant inside a giant heart made of balloons. Before the indictments, he regularly posted heartfelt messages on his Facebook page to his constituents and campaign supporters, always signing off, “God Bless You and Thank You for your continuing support.”

While Treviño has considerable support from the public, it’s the backing of the county’s inner circle of power brokers that really matters. Treviño is close with Rene Guerra, the county’s district attorney since 1979, for whom he worked as a criminal investigator and task force commander for 17 years before becoming sheriff. And he is well liked by County Judge Ramon Garcia and the county’s commissioners. In the rough-and-tumble, backslapping world of Valley politics, where campaign season never ends, Treviño always has skin in the game. “The sheriff is a great politician,” a former deputy, who asked to remain anonymous while discussing the sheriff, told the Observer. “He knows how to get elected, and he’s good at it.”

In November Treviño was exultant, having just won his third re-election with 80 percent of the vote, despite having two opponents. “I don’t think I’m entitled to this position,” Treviño told a local TV reporter at his celebration party. “This office belongs to the people. And this shows that we do have the confidence of the people.”

Treviño, a Democrat, also had the confidence of federal officials in Washington, D.C. Unlike more politically polarizing border sheriffs, he eschews talk of “narco-terrorism” and “border spillover,” instead emphasizing his agency’s role in reducing crime rates in Hidalgo County and the relative safety of the U.S. side of the border. In 2009, Department of Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano appointed him vice chair of the Southwest Border Task Force Committee, to advise her on security and other issues along the border.

Even after his son’s indictment for drug smuggling, the sheriff remained a popular figure untouched by the growing scandal. The day after his indictment, Jonathan was released on bond into his father’s custody and placed under house arrest at his parents’ modest, ranch-style home in McAllen, where he has lived for the past four years. “As sheriff of this county, I am obligated to do the right thing for my constituents,” Treviño told reporters after his son’s court appearance. “We are fully cooperating with the investigation, but as a father, I have a duty to my son and family.”

Many in the county seemed to sympathize with the sheriff. Treviño’s Facebook page was flooded with messages of support. “It is sad to see how quickly people pass judgment, no one is perfect and mistakes are made,” wrote one resident. “I respect Sheriff Treviño for standing behind his son in this difficult time and still [sic] stand for the oath he has taken as the Sheriff.” The short, stout sheriff with slicked gray hair and neatly trimmed mustache had an easy affability that made him approachable. He seemed like a man you could confide in.

But the deputies who worked for Treviño say there is another side to him that the public rarely sees. Gerardo Vela was a deputy in the Hidalgo County Sheriff’s office for nearly a decade before he was forced out in July 2012. Vela was fired for wearing a wire to document what he claimed was official oppression by supervisors. Texas law forbids elected officials from forcing their employees to perform personal or political work for them. The former deputy says he was instructed to work a polling place to aid the sheriff’s campaign, but when he tried to claim comp time for the hours, he was put under investigation by the sheriff’s Internal Affairs division, which later led to his firing. “Everybody is forced to go along,” says Vela. “They know it’s wrong but they go along with it because they are afraid to lose their jobs.”

There was tumultuous change in the agency as soon as Treviño took office in 2005, says Vela and two other former deputies who asked to remain anonymous because they feared retribution. The new sheriff stopped basing promotions on written exams and years of service as his predecessor Henry Escalon had done, instead leaving promotions up to his personal discretion. Suddenly, rookies—many of whom had ties to politically connected families in the county—were getting coveted positions that used to take years to acquire. Treviño also began pushing deputies to sell fundraising tickets to pay off his campaign debt. “Experience didn’t count anymore,” Vela says, when it came to promotions. “Only who you knew and what you had done to please the sheriff.”

The other two deputies, who asked to remain anonymous, backed Vela’s claims that they were forced to buy fundraising tickets and campaign for the sheriff’s re-election or suffer demotions and harassment. The deputies say they were instructed by Commander Joe Padilla—Treviño’s right-hand man—to sell the fundraising tickets. What they didn’t sell they would have to buy, Padilla told them. Some deputies even took out loans to buy tickets and meet their quotas and win favor with the new sheriff. “The environment that he’s built is nepotism, favoritism and cronyism,” Vela says.

When contacted by the Observer, Treviño said he found the former deputies’ allegations offensive. “It’s absolutely ludicrous for any elected official, especially one as high profile with as large of a department as I have, to conduct himself in that way. It’s illegal, and I categorically deny it. I won the primary and general election with 80 percent of the vote. I don’t need to force anyone to work on my campaign.”

The Dance Crew

Many deputies believe that Jonathan was hired by the Mission Police Department in April 2006 as a favor to the sheriff, so that Treviño could keep his son close yet avoid nepotism allegations. In little more than a year, the rookie was promoted to a coveted investigator position and given a $2,500 pay raise. This much is known from official records. But trying to find any documents on the creation of the Panama Unit or its reason for being is next to impossible.

Pat Medina, Sheriff Treviño’s chief of staff, said no such documents exist. “The creation of the unit was an oral event made by the sheriff and former Mission Police Chief Leo Longoria,” she told me. I asked what year the unit was formed, and Medina said she had no record. After some prodding, she faxed me a single sheet of paper with the names of the five Panama Unit members who had been sheriff’s deputies up until their indictment or resignation in December: Eric Alcantar, Salvador Arguello, Claudio Mata, Fabian Rodriguez and Gerardo Duran. Their salaries mostly ranged from $40,000 to the $42,000 Mata made as the veteran of the unit. (Treviño was being paid $49,000, according to Mission Police Department records.)

Alexis Espinoza, who was indicted in December, worked as a Mission police officer and a liaison with ICE. And while Espinoza, the Hidalgo police chief’s son, was never an official member of the Panama Unit, he spent time with them on duty. Alexis and Jonathan were friends. Unlike the other members of the unit, they shared a common bond. Both lived in the shadow of their fathers’ law-enforcement careers. “Lupe had been a narcotics investigator for many years before he became sheriff,” says a former deputy who asked to remain anonymous because he feared retribution. “I think Jonathan really wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps.”

The sheriff’s goal, says a former narcotics investigator who also asked to remain anonymous, was to see Jonathan win Texas Narcotics Officer of the Year—a prestigious award given to the investigator with the most annual arrests and drug seizures in the state. “The sheriff told my supervisor, ‘I want you to nominate him for the award,’ but my supervisor couldn’t because Jonathan didn’t have the stats for it.”

Though records are sparse, current and former deputies say that by 2007, Jonathan, at age 23, had his own narcotics task force. All seven members were in their 20s. Not one of them had served in law enforcement longer than a couple of years, with the exception of Claudio Mata, who had been a deputy for four years. The rookie Panama Unit was roaming Hidalgo County in unmarked cars, working undercover. At first they were unsupervised until complaints got back to the sheriff, who appointed Lt. Roy Mendez to keep tabs on them, according to law-enforcement sources and press accounts. “Everyone said they would fall apart because they were not experienced. They had no oversight and no investigative experience,” Vela says.

“We had a nickname for them. We called them the Dance Crew because they looked like a bunch of young undisciplined guys,” says another former deputy who still works as a local police officer. By 2010, Jonathan had made a name for himself in law enforcement, but not in the way anyone could have imagined. The Panama Unit was not only creating chaos in the underworld, but also angering honest cops who resented the unit’s growing reputation for corruption and impunity. “They say the original mission of the unit was to target drug dealers from Mission and western Hidalgo,” the former deputy told me. “But actually they ran around in every part of the county. They were doing home invasions. They were stealing [drug] loads. They were ripping people off, stealing property and stealing money.”

In the small town of San Juan, just east of McAllen, the Panama Unit had done at least three busts, which the town’s police chief, Juan Gonzalez, is now scrutinizing to see if any crimes were committed. Rumors about the unit had been circulating among county law-enforcement officers for years, Chief Gonzalez says. “No one wanted to work with this unit. So when no one wants to work with this unit, then there’s some truth to what’s going on.”

Maybe it began as a joke or a dare for the young deputies on the Panama Unit to rip off the county’s drug dealers. Who cared if a bunch of thugs lost their drugs and their money? It turns out a lot of people did. It certainly was no joke for the dealers who lost loads worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. The Gulf cartel was unsympathetic. Cartel hit men kidnapped some local dealers who had lost their drug loads. Most were never heard from again, according to law- enforcement sources. “The Panama Unit jacked a lot of people,” says a deputy who works in narcotics and keeps in touch with several confidential informants in the drug world. “[The Panama Unit] probably never thought that these people are responsible for those loads back in Mexico, and they didn’t have any paperwork or proof. In Mexico you get the money or you die. A lot of people got killed over there in Mexico.”

Jonathan started receiving death threats, says a former narcotics investigator. “There’s still something of a code of honor among drug dealers,” he says. “You don’t just go and jack anybody’s dope because at the end of the day that guy might be working for the same guy you’re working for. But then you have these independent gangs and all they do is steal dope, and they don’t care. Well, Jonathan fell into that group. They didn’t care who they stole dope from, and they didn’t have any alliance with anybody. They were working for themselves and that’s where they got their troubles.”

Too Much John Wayne

On a January afternoon, black ash rained down over McAllen as the sugar cane fields burned near the river. I was on my way to meet Robert Caples, a former sheriff’s deputy, at a local café. Since 2005, Caples had been engaged, with little success, in a one-man crusade to root out corruption in the sheriff’s department.

But in the last two years, as the Panama Unit allegedly plundered unchecked, fed-up deputies and police officers had begun to leak to Caples affidavits, covertly recorded video and audio, and other documents, which he’d passed on to the FBI and Texas Rangers. He’d also leaked investigative reports and videos to the media, and through a Facebook page he’d formed for a group he called American Protection Specialists, which, according to its mission statement, was a “movement to protect our Texas-Mexico border in the Rio Grande Valley from drug cartels and corruption through reconnaissance and well-trained armed defenders.”

In the past year, the group’s Facebook page, with its grainy videos and leaked documents, had become Hidalgo County’s version of Wikileaks, and Caples the county’s very own Julian Assange—though Caples looked pained when I brought up the comparison.

Walking ramrod straight in a white T-shirt under a white button-down dress shirt and a military buzz cut, the former Marine was easy to spot. He shook my hand forcefully and sat down with a cup of black coffee. Caples, 42, was born and raised in McAllen. After coming back from the first Gulf War in 1992, he says, he was naïve to the inner workings of his hometown. “I didn’t know anything about politics or corruption. I was gung-ho to make a difference. I guess I’d watched too many John Wayne movies.”

So Caples became a deputy in 1993. The next year, Sheriff Brigido “Brig” Marmolejo was indicted on bribery, money laundering and racketeering charges. Most of Hidalgo County’s officials, including the director of the Head Start program, were arrested the following year in another federal corruption case. “Basically just about the entire Hidalgo County government was indicted in 1994,” Caples says. After Sheriff Marmolejo went to jail, a no-nonsense Army veteran named Enrique “Henry” Escalon took over. “He had a very tight chain of command and was very disciplined. You couldn’t kiss his ass because he wouldn’t allow it,” Caples says. Escalon created the county’s first corruption task force. “We went after everybody. No dirty politician was safe and therefore the sheriff didn’t have many friends.”

Escalon’s deputies investigated County Judge Eloy Pulido, and arrested one county commissioner twice. (Each time his charges were dismissed by Guerra, the district attorney who’s been in office since 1979.) Caples relished his work, becoming a deputy sergeant, a SWAT team leader and law-enforcement instructor. Then it all came crashing down with an off-duty DWI arrest in 2004. Sheriff Escalon fired him. “He had a zero-tolerance policy,” Caples says. “I was in complete support of it, and I had to live by my own standard.” After his dismissal, Caples found work as a private investigator. He soon became fed up with the way Lupe Treviño ran the sheriff’s department.

In November, Caples ran against Treviño for sheriff and suffered a crushing defeat with less than 20 percent of the vote. The race had been a bruising one, with Treviño dredging up skeletons from Caples’ past: the DWI in 2004, and a charge in 2010 of sexually assaulting his ex-girlfriend’s teenage daughter. (He was acquitted that same year. “It was a false allegation made by my ex-girlfriend and her daughter,” Caples says. “We were involved in a mutually obsessive relationship. We were crazy in love, you know what I mean? But we were no good for each other.”)

In turn, Caples leaked investigative records to the McAllen Monitor showing that the sheriff’s brother, Pablo Treviño, a juvenile probation officer, had been accused of making sexual advances toward teenage girls under his supervision, but that the investigation had been dropped by the sheriff’s office. After the story was published, Sheriff Treviño demanded that the Monitor turn over its copy of the “stolen” case file or his deputies would raid the newspaper, according to the Monitor.

Caples, who ran as a Republican, says he didn’t intend to win. “I didn’t raise any money for the race and I didn’t spend any money. I only ran to have a platform on which to expose corruption.” Still, voters remained skeptical. Treviño characterized Caples’ accusations as politically motivated and his character as suspect. “This is the first time in four years that someone questions my integrity,” Treviño told the Monitor in the story about his brother’s investigation. “And the person who is questioning my integrity is an alleged criminal—an accused child rapist, a disgraced police officer and a hit-and-run artist.”

In November Caples lost miserably, but by December he was feeling vindicated after Treviño’s son and other members of the Panama Unit had been indicted. “The voters received my message, they disregarded my message, and now they know what I was talking about.”

People had lost their lives and the county’s law enforcement community had been plunged into turmoil, all because some rookie cops had allegedly gone dirty. “I think the cartel, at least from everything I’ve been told, has no interest in killing cops who are just doing their jobs,” Caples says. “They understand that you win some and you lose some. They are never going to get rid of law enforcement, and we are never going to get rid of drug traffickers. But what they can’t stand is dirty cops.”

Law enforcement felt the same way. “This has impacted all of law enforcement down here,” said San Juan Police Chief Juan Gonzalez, who sympathizes with Caples’ crusade but says he’s not a member of American Protection Specialists. “I’ve received hundreds of calls from officers across Texas wanting to know what’s going on down here with the corruption. We have a lot of really good police officers and very good police departments that are striving to be the best they can. Yes, we are susceptible to corruption, but I strongly believe that corruption is preventable if we don’t turn a blind eye to it.”

You only have to look across the river, he says, to see how corruption can destroy a society. In Mexico, officials colluded with criminals and corruption ran rampant until it destroyed rule of law. Gonzalez didn’t want to see the same thing happen in his own community. “I think the sentiment is that there’s been a lot of damage done,” he says of the sheriff’s department scandal. “The only way to rebuild it ultimately is for the leadership to step down, because the conduct of your employees reflects your leadership.”

But Sheriff Lupe Treviño is not going anywhere. Shortly after his son’s indictment, he posted a defiant message to supporters on his Facebook page.

“Thank you for the overwhelming support that we have received from our true friends. It is during these difficult times that you identify who your true friends are. My family and I are very fortunate to have such a large circle of close friends. Unfortunately there are those that will take advantage of a tragic opportunity to kick a man while he is down. Whether it be for future political or personal reasons, now is not the time to further a family’s pain. You all have read comments from only one police chief and have heard him on only one tv station. Living in a glass house is a precarious situation. I am proud to report that the majority of the major RGV police chiefs, heads of federal law-enforcement agencies, and heads of state law-enforcement agencies have called offering their support. Those are true leaders and men. Keep your prayers coming and the HCSO will continue to be a leader for at least 8 more years to come under my leadership. Thank you and God Bless You. Sheriff Lupe Treviño.”

After his son was indicted, I phoned the sheriff. The media-friendly and usually forthcoming Treviño had once given me his cell number and told me to call him anytime. True to his word, he answered immediately, but he was reserved. “My situation now is that I’m between a rock and a hard place. My son is a member of the unit, but they were not working for me. I’m declining this interview only because my son is involved, and it’s a pending legal matter,” he said. “Responsibility is what I stand for … that I was blindsided by something like this is just devastating for me.”

Treviño sounded like he sincerely meant it—even though the law-enforcement officers I spoke with say it’s unthinkable that the county’s most powerful lawman didn’t know what his own son was up to. Especially when they lived under the same roof.

In September, Treviño reflected on his career when he received a “Law Enforcement Life Achievement” award from the City of Edinburg, where he’d gotten his start in 1972 as a police officer. As always, his sons and his legacy as sheriff were uppermost in his mind. Did he have any idea what was to come just three months later? How could he not see it coming? “I am very proud of my origins and will be forever indebted to those that helped me be the man I am today,” he told the mayor and assembled local dignitaries. “My legacy will be based on the values that I will pass on to my sons and to my employees.”