The Arson Files: After Serving 25 Years, Ed Graf May Finally Receive New Trial

In 1988, flawed arson evidence sent Ed Graf to prison for life. He may soon be free.

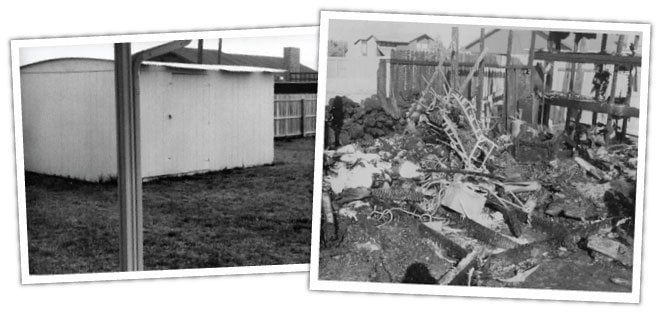

Above: The backyard shed, before and after the fire that killed Joby and Jason Graf.

Ed Graf had waited 25 years for a chance to prove his innocence, and late last week, he finally got it.

Graf was convicted in 1988 and sentenced to life in prison for a crime that stunned his suburban Waco community. Prosecutors alleged Graf had dragged his 8-and 9-year-old stepsons into a shed behind his house, set the shed on fire, locked the doors, and burned the boys to death. Graf maintained his innocence from the start, contending the fire was accidental. In the quarter century since Graf’s conviction, the field of fire investigation has advanced considerably, and the evidence that sent Graf to prison for life is now widely viewed as junk science.

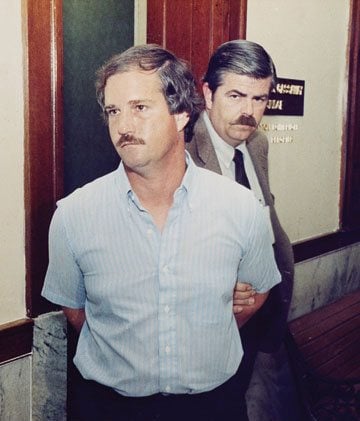

I investigated Graf’s conviction in 2009 as part of a series on flawed arson cases. (Read our original story on Graf’s case here.) During my reporting on the case in 2009, Graf refused my interview request. So until sheriff’s deputies led him into a courtroom on the first floor of the courthouse in Waco on Friday, I’d only ever seen Graf in photos. In 1988, Graf, then in his mid-30s, had strong shoulders, dark bushy hair, a neat mustache and the round face and midsection of comfortable family life. The man who shuffled into the courtroom on Friday and silently took a seat next to his attorney bore little resemblance to those old photos. Now 60, Graf’s face is taut, his hair gray and closely shaved. He sat shackled, shoulders slumping in his gray McLennan County jail jumpsuit, and said almost nothing while other men began the hearing that would determine his future.

Over the next two hours, a nationally known fire scientist eviscerated the forensic evidence in Graf’s case. While the flawed physical evidence had helped secure his conviction, it was circumstantial evidence that made Graf appear guilty.

The fire broke out late on a sweltering afternoon in August 1986. Graf had picked up his stepsons Joby and Jason, and arrived at his home in the Waco suburb of Hewitt about 5 p.m. Roughly 10 minutes later, neighbors saw smoke pouring from the shed behind Graf’s house. Joby and Jason were inside. Flames consumed the shed in minutes, and Ed Graf was the only other person home. Ed’s then-wife Clare, who taught kindergarten at a local elementary school, rushed home to find that her two sons from a previous marriage were dead.

At first, investigators thought the fire an accident, and that assumption led to destruction of the fire scene. The shed was bulldozed and hauled off to a local dump. Firefighters thought they were doing the Grafs a favor; they didn’t want the couple to see the burned shed when they woke up the next morning. In fact, they were destroying critical evidence.

Shortly after the fire, Clare took the 6-month-old baby she had with Ed and went to stay with her relatives. Her family soon began to suspect that Ed Graf had set the fire. He had taken out life insurance policies on the kids just months before the fire (and tried to cash in the policies after their deaths). He had insisted the boys keep the tags on their new school clothes (and later returned them). He had neglected to buy more cereal for the boys. At Graf’s 1988 trial, then-prosecutor Vic Feazell told the jury, “Everything indicated that Ed knew that those kids wouldn’t be around.”

There were simple explanations for all those things: Graf thought life insurance policies a good investment, a way to save money for college; he kept the tags on the clothes in case they didn’t fit; and he simply hadn’t gone grocery shopping. But the circumstantial evidence backed by two fire investigators claiming the physical clues pointed undoubtedly to arson was enough to send Graf to prison for life as a child killer.

But a few people around Waco had long believed that Graf was innocent and the fire was an accident—perhaps started by Joby and Jason themselves (neighbors and teachers testified they had seen the boys play with starting fires before). Don Youngblood worked as a defense investigator on Graf’s case. Most of his clients were guilty, he says. “Mr. Graf is the one case out of 50 that I’m thoroughly convinced that he did not do it,” Youngblood told me in 2009. “It’s one case I never forget about.”

It took a quarter century but on Jan. 11, Ed Graf finally got another day in court to contest the evidence. Retired state district Judge George Allen convened the hearing to decide on Graf’s writ of habeas corpus, his request for a new trial, which Waco innocence attorney Walter Reaves had filed shortly after my 2009 story was published.

The star witness was Doug Carpenter, a nationally known fire scientist who works for Maryland-based Combustion Science and Engineering. Reaves had asked Carpenter to evaluate the arson evidence in the case. On the witness stand, Carpenter said he had used the scientific method to test various hypotheses about how the fire started. Carpenter left no doubt about his conclusion: The fire at the Graf house had been accidental.

“Is there anything in any of the evidence you’ve seen that would indicate this was an intentionally set fire?” Reaves asked.

“No,” Carpenter said. A few moments later, he added, “There is no evidence to be able to formulate a valid hypothesis that this is an incendiary fire.”

In my 2009 story, I detailed the flawed arson evidence against Graf—so-called pour patterns on the floor and burn patterns on the wood. Investigators at the time misread these clues using now-outdated understanding of fire. They believed the “pour” patterns and burn marks on the walls and supports showed that Graf had poured gasoline on the floor of the shed, lit the gasoline and locked the boys inside. Austin fire scientist Gerald Hurst told me in 2009 that these “old wives tales” about fire, now debunked, revealed nothing about how the fire had started. The burn patterns were simply evidence that the shed had been subjected to an intense fire that consumed the entire structure. Hurst also contended that the door to the shed must have been open—or the fire would have died out from lack of oxygen. He concluded the prosecution’s theory of arson didn’t square with the evidence.

Hurst told me in 2009 that the flawed evidence in Graf’s case was as bad if not worse than the disproved evidence in the now-infamous Cameron Todd Willingham case. (Willingham was executed in 2004).

Carpenter agreed with Hurst’s examination of the burn patterns. (Nationally known fire scientist John DeHaan issued a report in the case that reached similar conclusions). But Carpenter added even more compelling scientific evidence that the fire was accidental. He testified that the toxicology of Joby and Jason’s blood proved the fire wasn’t set with gasoline.

People die in fires in two common ways, Carpenter said: heat exposure and inhaling carbon monoxide fumes. Carbon monoxide remains stable in the blood after death and can offer clues about how the fire started.

Victims of quickly spreading gasoline fires that overcome victims with heat exposure have lower levels of carbon monoxide in their blood. That’s because they stop breathing fumes rather quickly and died of heat exposure.

Victims of accidental fires that smolder in a small area and then engulf a part of the room or a piece of furniture leave a different signature in victims’ blood. Carpenter explained that experiments and research shows fires can burn intensely in confined spaces—such as inside a cabinet or under a chair. Those intensely burning, confined fires can emit deadly levels of fumes, including carbon monoxide. He cited one case he had worked on in which a kitchen cabinet had caught on fire. The flames inside were intense, though largely confined to the cabinet. But the carbon monoxide killed four people, even though the rest of the house was largely undamaged.

Fire victims breathing in carbon monoxide will first become disoriented, then will pass out but continue breathing in the fumes and eventually die even before they’re burned. Victims who die this way have extremely high levels of carbon monoxide in their blood—as Joby and Jason Graf did.

Autopsies on the boys showed carbon monoxide levels in their blood were 76 percent and 86 percent. (People become incapacitated when their CO levels reach 30 percent; deaths occurs at 50 percent. CO levels of 80-90 percent are extremely high and very unusual, Carpenter said. Levels that high indicate Joby and Jason died of fumes from a nearby confined fire in the shed before they were burned.

Carpenter said the carbon monoxide levels disprove the theory of an arson fire started with gasoline—a fire in which victims are burned quickly and typically have carbon monoxide levels of 20 percent.

The toxicology evidence offered by Carpenter was powerful, and McLennan County Assistant District Attorney Alex Bell struggled, and ultimately failed, to poke holes in it on cross-examination. In fact, prosecutors have challenged little of the new fire science evidence in the case.

Carpenter said that while the toxicology and fire pattern evidence point to an accidental fire, he can’t say how exactly the fire started. Reaves asked if the evidence would be consistent with the boys lighting the fire, which became intense in a confined space, and they were overwhelmed by the fumes and unable to escape even though the door was open. “I see nothing to disagree with that,” Carpenter said.

If the fire was accidental—as the evidence suggests—then there was no crime of arson and Graf is, by definition, innocent.

The parties will reconvene for another hearing on Jan. 24 when Judge Allen will issue his recommendation in the case. It will then go to the Court of Criminal Appeals, which will make the final ruling.

After the hearing, as Graf’s family members filed out of the courtroom, Reaves said he was optimistic. “I feel good about it. I think at a minimum we’ll get a new trial.” He said even if he couldn’t definitely prove Graf’s innocence, he has shown that the evidence used to convict Graf was unreliable, which would force a new trial. It seems unlikely that prosecutors would attempt to retry Graf given the flawed evidence. If he wins a new trial, Graf may be released from prison.

If so, he would be one of the first Texans wrongly convicted of arson to be freed. Graf’s case—along with the case of Alfredo Guardiola, which I also investigated in 2009—are part of a wide ranging review of arson convictions by the Texas Forensic Science Commission along with the Texas Innocence Project and the Texas Fire Marshal’s Office. There are hundreds of people in Texas prisons on arson convictions.

Getting out of prison won’t correct the injustice. Graf once had a life many would admire—a steady job, a nice home, a growing family. The fire and his conviction for starting it, took all that away. Graf’s son—just six month’s old at the time of the fire—grew up believing his father was a murderer; he changed his name and cut off all contact with his father.

When I pointed out to Reaves that the hearing seemed a positive development for his client, the attorney chortled. Yeah, he said, you wait 25 years in prison and something good might happen.