King’s Gambit

Daniel King's quiet mission to transform public education in South Texas.

A version of this story ran in the September 2015 issue.

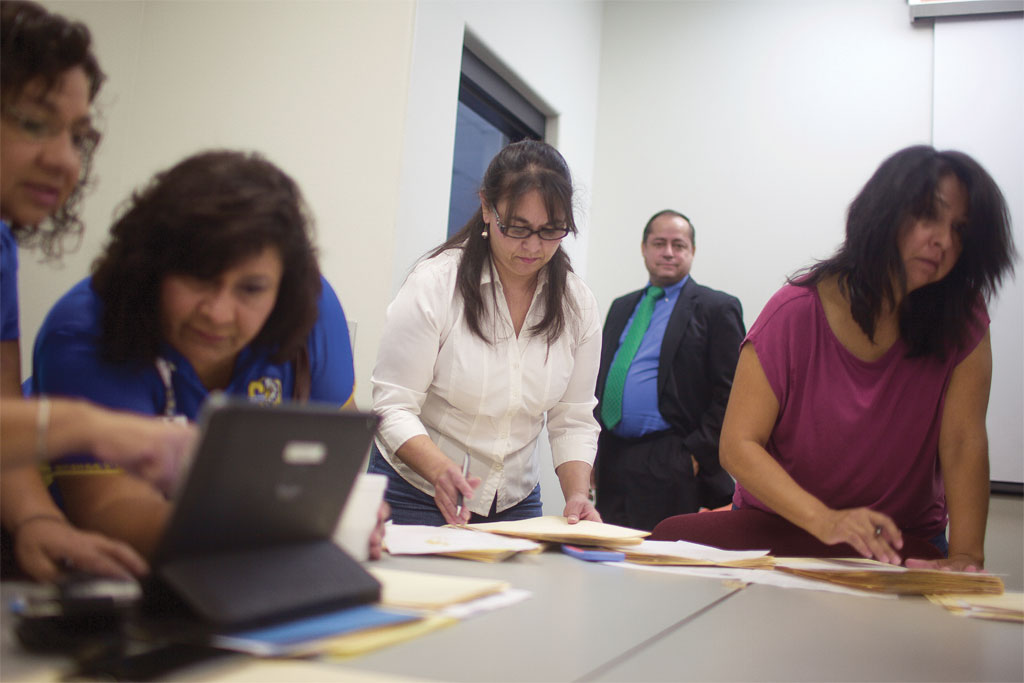

Above: Daniel King, dressed in his usual uniform, talks with staff members about the new school year.

Gazing up from the sea of graduates on the arena floor, it would have been easy to miss Daniel King. In a black, blue-trimmed robe, with a floppy doctoral tam on his head, he was hidden onstage behind rows of other officials and academics at South Texas College’s spring commencement at the State Farm Arena, a mile from the border. King never rose to speak, shake hands or mug for the cameras, but hundreds of the graduates in the crowd probably would not have been there without him. The graduation was another milestone for the juggernaut that King has built to move young people through college while they’re still in high school.

Of the 5,700 degrees and certificates the college awarded that weekend in May, 485 of them went to students in the Pharr-San Juan-Alamo (PSJA) Independent School District, where King has been superintendent for the last eight years. Those students wouldn’t even get their high school diplomas for another two weeks. Hundreds more degrees from South Texas College went to students from other nearby high schools that have adopted the “early college for all” approach King has pioneered over the last decade.

The early college movement is growing fast today — a free head start on higher education is especially alluring in a time of boundless student debt — and King is widely recognized as the guy who’s teaching the nation how to make early college work for everybody. While dual credit and Advanced Placement courses have been around for decades, they have been most prevalent in wealthy districts that can afford special programs for a few advanced students. But this fall, every one of PSJA’s high schools will be an early college campus. King has made early college universal in a district where 89 percent of the students live in poverty and almost half speak limited English.

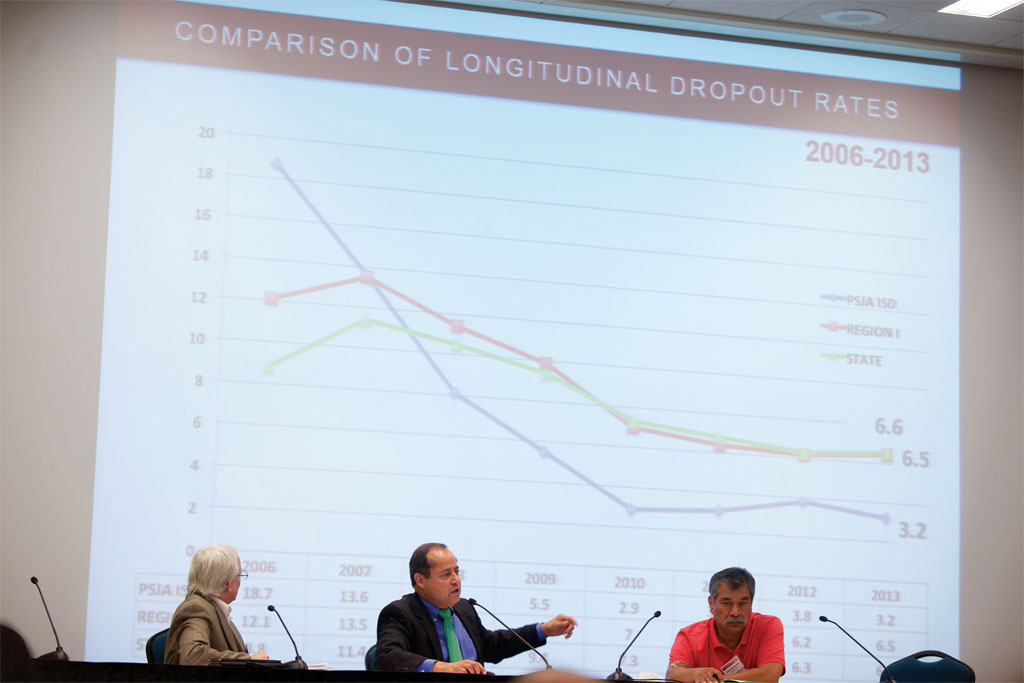

In the past eight years, King has raised his school district’s graduation rate from 60 to 92 percent, getting students to return to high school and graduate by connecting them with college or a career. At the same time, PSJA is expanding its reach into the community, providing teachers for early education programs outside the schools, and offering free adult classes to help parents learn English, earn their GEDs and apply for citizenship. In an era of education reform defined by smooth-talking disruptors and schools run like tech startups and fast-food chains, the unassuming King and his 100-year-old school district suggest another path to improvement: reinvention that’s bold but measured, supported by a core of veteran educators, and built to carry the entire community.

The 61-year-old King does not possess the brashness it takes to be a celebrity school chief — he’s not one to pose, like former Washington, D.C., schools chancellor Michelle Rhee once did, broom in hand on the cover of Time, pledging once and for all to take out the trash. Donning his academic finery for a graduation ceremony is about as showy as King gets. But he’s drawn attention because the numbers suggest he has accomplished that rarest of things in education: a bona fide school turnaround, one that transcends any short-term gains from accounting gimmicks or test prep drills. How has he done it? That’s the question that has made King such a popular headliner on the policy luncheon circuit, along with the inevitable corollary: Can it work elsewhere?

Today, King is a soothsayer sought out by a broad array of politicians and educators. His work has been heralded by the Obama administration, the George W. Bush Institute, the Clinton Global Initiative and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. He’s also won support from grassroots groups such as ARISE and La Unión Del Pueblo Entero, which advocate for more radical change and community-centered education in the Rio Grande Valley. The most powerful voices in the bitter debate over American school reform, though they agree on little else, agree on Daniel King.

King was the fifth of 10 siblings raised by Baptist missionary parents on a farm in Rio Hondo. His father served in the Navy in World War II. In a particularly dicey moment in the Pacific aboard the USS Denver, his father pledged that should he survive, he’d devote the rest of his life to missionary work, so when he returned from war, the family packed into a car and headed toward Mexico. But a brief stop in Harlingen to minister to braceros brought from Mexico for temporary farm work convinced him to stay in the Valley and open a church. As a child, King helped deliver clothes to bracero camps and joined in the games and classes his parents held in the backyard. At age 8, he began spending his summers working alongside other children in the fields, picking cotton, cabbage and tomatoes.

King’s roots in the Valley have been an asset throughout his career, first to relate to students, and more recently as he builds partnerships between his schools and the area’s other institutions. “Maybe because of the way I grew up, with my parents ministering in these communities, and working in the fields, and maybe I have an accent,” King says, “a lot of people make the assumption that I’m Hispanic, but I’m not.” (More than one person I spoke with made that assumption.)

Donning his academic finery for a graduation ceremony is about as showy as King gets.

King was a good student but says he “lacked confidence in a lot of ways.” His parents expected him to go to college, but once he enrolled at Pan American University in Edinburg, he didn’t have much direction. The way King tells it there was no great epiphany — he liked helping kids, so he studied to be a teacher.

Since he began teaching in 1977, King has spent his entire career in three school districts within a few miles of one another. He coached sports, taught history and health, and in 1988 took a job as the high school principal in Hidalgo, a small town south of McAllen just across the border from Reynosa. He was the ninth person to hold the job in 13 years.

“I developed, over time in my early years of teaching,” King says, “a very strong belief” that the right education system can lift people out of poverty. “I’ve committed my life to making it clear that it’s our job as a society to figure out how to … not have continued generations go by and have this part of the state always be low-level.”

Alvin Samano, who is the facilities director at PSJA today, was a sophomore in high school during King’s first year teaching at Hidalgo. Samano remembers that when he broke his leg playing football, King stayed by his side all the way to the hospital and visited daily. King was the health teacher and the closest they had to a team trainer. “We had graffiti everywhere, we had low scores, we were always getting beat in athletics, and he transformed it just like he transformed PSJA,” Samano says.

King says he was always focused on helping kids plan for life after high school, but it wasn’t until 2005 that he heard of early college. That year, the president of the University of Texas-Pan American told him that the Gates Foundation was offering a grant to take 100 students from a high school and make them the inaugural class at a new small high school on the university campus. They’d earn 60 hours of college credit and an associate’s degree, all for free and while still in high school.

King liked the idea of early college, but not the prospect of choosing just 100 students for it. He countered with an offer to use the entire 800-student Hidalgo High School as an early college laboratory. The funders told him it wouldn’t work, that the model had to be a small school — and that’s how the meeting ended. Months later, King was surprised to learn that his proposal had sparked a debate between the Gates Foundation and the UT officials, and they’d approved his proposal after all. The high school opened in fall 2006 as Hidalgo Early College High School. It was the first campus-wide early college school in the country, and by late 2007 the buzz about Hidalgo and King began in earnest. Bill and Melinda Gates visited to see the school firsthand, and U.S. News & World Report ranked the school No. 11 nationwide. King wasn’t there to enjoy the accolades — he had just taken a job at neighboring PSJA, a district 10 times the size of Hidalgo, and one that was in shambles.

The previous superintendent at PSJA, longtime educator and political veteran Arturo Guajardo, had stepped down amid a federal bribery investigation that also ensnared three school board members and a construction contractor. According to a report at the time from the local paper The Monitor, an indictment claimed Guajardo and the board members “accepted bribes of cash, vacations, sex and entertainment in exchange for funneling projects to a preferred group of Rio Grande Valley businessmen.” Outbreaks of gang violence were commonplace in PSJA middle and high schools, fewer than two-thirds of the district’s high school students graduated on time, and the schools produced years of poor showings on state tests. Aurelio Montemayor, an education specialist at the Intercultural Development Research Association, succinctly describes a sense many others shared about the district before King’s arrival: “PSJA was really in the toilet.”

King came alone, without a cabinet of favored lieutenants from his last job, and he didn’t shake up the district staff. He focused first on the most glaring problem: dropouts. He led a door-to-door campaign to lure students back to the district. Many of those he recovered attended classes at an old Wal-Mart that King had converted into the PSJA College, Career and Technology Academy. There, students age 26 and under could earn college credits through South Texas College while they completed their high school coursework or studied for state tests standing between them and a diploma. As veteran PBS education reporter John Merrow described it in a 2012 story, the pitch went like this: “High school didn’t work, so come on back and let’s try college.” The year before King arrived, 237 high schoolers had dropped out; he and his staff recovered all but 14.

King has made early college universal in a district where 89 percent of the students live in poverty and almost half speak limited English.

King’s pitch made sense to Julio Viramontes, who would have graduated with the PSJA High School class of 2000, but failed his state math test three times before dropping out after his senior year. Rather than return to school for yet another retake of the test, he settled into work at Pizza Hut and at a furniture warehouse. It was only after King opened the career academy that Viramontes’ mother, who worked at the district office, urged him to sign up. Taking classes in the mornings before his afternoon shift at work, Viramontes earned credits toward a degree in criminal justice, and took evening and weekend math classes to prepare him to retake TAAS, the standardized test that preceded TAKS and STAAR. He passed it in 2010, and went on to get his bachelor’s degree.

Viramontes quit his warehouse job the day he passed the test, and although his present occupation requires little advanced education — he’s a pro mixed martial arts fighter — he says returning to school changed his perspective. Without the jolt of motivation that came from his late success in school, he says, “I don’t think I’d be doing MMA. I’d probably still be working jobs that I hated.”

Viramontes has three children in PSJA schools today, the oldest in middle school. He’s gone, in just a few years, from a high school dropout to a college graduate looking forward to his own children’s college careers. That multigenerational approach is key to PSJA’s plans. While King has cast a wide net for school-age students, he’s also opened adult education centers in old school buildings, welcoming parents into the school community with classes in English and GED prep. King has also lent the school district’s support to Head Start and private day care, which often lack certified teachers.

In all these programs, King tries to cover as many students as possible, not just those who sign up first or have the highest grades. The same principle is driving PSJA’s early college programs, and that’s the innovation that has drawn so much enthusiasm from outside. PSJA opened its first early college high school in 2008, King’s second year with the district. The way he tells it, the school was a stroke of luck: South Texas College had been planning an early college program with another district in the area, but the district had bowed out. King got a call from the college: Did he want to bring PSJA on board instead?

College officials had in mind a single early college school, but as he had in Hidalgo, King proposed an all-or-nothing deal. He’d only agree to a single campus as a first step toward starting early college at all PSJA high schools. That had never been done before, and nobody knew if it would work. That first campus was a magnet program, focused purely on academics, with no sports and few clubs. It was housed in a set of trailers during its first few years and students took Friday classes at a South Texas College campus. This fall, true to King’s deal with South Texas College, every high school in PSJA will have an “early college” designation from the state; nationwide, no other district of PSJA’s size has made early college universal.

It’s increasingly normal in King’s district for students to finish a college degree before they finish high school. Three years ago, 67 PSJA students had a chance to walk in the South Texas College commencement; four years before that there were two, the district’s first. By 2017, King wants 90 percent of the district’s high school graduates to make that walk across the stage.

The district has focused on courses in fields including nursing and welding, which pay well, are in high demand, and require no education beyond what a high school student can earn in two years. Students who go on to a university with early college credit are far more likely than those without it to stay in college and finish within four years. Even with a college degree, Hispanic students from poor families face far more challenges than Anglo college grads. Still, regardless of ethnicity, a graduate with a bachelor’s degree tends to earn double the income of a student who only finished high school.

I had asked, in the course of reporting this story, about sharing a little down time with King, to get a sense of his personality in a less formal setting. Maybe he had a hobby that would speak to his character? I’d read, for instance, that King enjoys going for bike rides. With Mike Miles, the high-profile former superintendent of Dallas ISD, there was no shortage of ready-for-TV moments. Miles was quick to put himself on display — his penchant for epic movies, his dancing ability — to lighten the mood or motivate his staff. Talking with King and those around him, I was quickly convinced that it would be impossible to describe King through anything but his work. He and his wife, Sara, shared their first date at a dinner during a science expo at UT-Pan American; their courtship played out at their children’s softball and volleyball games at school.

“It’s not like pie in the sky, where we’ve found nirvana or whatever. It’s tough work. It’s challenging work. We regularly get disappointed.”

So on a morning in July, I took a seat in the back of a room in the district office that had all the charm of a dentist’s waiting room — rows of gray tables, gray walls empty but for a whiteboard — to watch King at work with the teachers leading PSJA’s bilingual education initiative. He often spoke of “breaking silos” and “thinking outside the box,” the verbal equivalent of motivational workplace posters. To a lay outsider, it wasn’t exactly an inspiring scene. But if authentic, systemic change is the antidote to sloganeering, quick-fix school reform, then maybe this is what it looks and sounds like.

As the meeting began, King handed out a multi-page memo on expanding PSJA’s dual language program. Crossing in front of the whiteboard in his standard uniform, a dark suit and colorful, patterned tie, King sometimes appeared dour as he listened or formulated an answer to one of his teachers. But his demeanor lightened as he explained his ideas, picking up speed as he delved into ever greater detail. King is at his most electric in moments like these, flitting between broad smiles and deadpan delivery, a bit like Bob Newhart in his ’70s sitcom — though certainly none of his students would get that reference.

King’s goal, he tells the teachers, is to start teaching high school Spanish to sixth-grade students — no great stretch, he figures, because so many speak Spanish at home. That would put them in seventh-year Spanish by the end of high school, which is as high as the state curriculum goes. Hardly anyone else teaches the level-seven course, which puts PSJA in a familiar position, alone on the edge. “The state doesn’t have it designed, so we’ve got to have it designed. The challenge is, we’re scaling like nobody else,” he tells his staff. “We’ve made some progress, but I haven’t been comfortable with how much progress.” Reaching an area of particular concern, he describes having “a little bit extra dissatisfaction.”

Administrators told me about King’s high expectations for them — that he can be tough, but it’s all for the good of the kids. That can be a kind way of describing schools that are miserable places to work in, with a boiler-room mentality to raise test scores at all costs. King says he’s set some hard goals for his principals — to grow their early college enrollment, for instance — but abandoned them after realizing they were too high. “I certainly haven’t used the turnaround model where you wipe out half the teaching staff and the administrative team,” he says.

Some PSJA teachers are organizing a chapter of the American Federation of Teachers, citing concerns about school discipline, along with not having enough uninterrupted preparation time, or freedom to speak out when they have concerns. The discipline criticism suggests a point where classroom realities may clash with King’s broad goal of keeping every student in school. PSJA refers far fewer students to disciplinary programs than nearby districts do, which is generally a good thing for students. But teachers vying for leadership spots in the union have said the policy undercuts their authority with students, and leaves them stuck with kids who shouldn’t be in class. King says his staff has been meeting with teachers about it, but that the district’s policy is sound, if not perfectly implemented at every school.

“There’s a science and there’s an art” to negotiating big changes with a staff and community, he says. “There’s trying to figure out where to push, and how hard to push here, and how hard to push there as you move forward. If you come in as a superintendent and you immediately get the whole community upset or you get the entire faculty upset, you’re probably not going to be there very long.”

In the school policy world, one great question follows any apparent success story: Can it scale? In other words, can this intervention, if applied to all schools in a major urban district, have the same kind of effects? PSJA has become a popular destination for lawmakers and educators trying to answer that question about King’s work. By now King is used to the attention, and he cautions anyone looking to PSJA for all the answers. “It’s not like pie in the sky, where we’ve found nirvana or whatever. It’s tough work. It’s challenging work. We regularly get disappointed. When you set big goals, we regularly run up against brick walls and from my way of looking at it, we’re still on the very, very early stages,” he says.

“I had really thought we could go quite a bit faster, and what I’ve found is a need to slow down.”

That sober approach is part of what makes PSJA’s story so compelling, especially after so many quick school-turnaround stories — Houston, Atlanta, El Paso — have imploded after a few years. King doesn’t sound like a guy who’s trying to sell you something, but others have been happy to sell it for him.

“He wasn’t going out and saying, ‘I know the answer, look at me, look at me.’ People were coming to him,” says Ida Musgrove, who was a longtime legislative director for former state Senator Leticia Van de Putte. “It’s not that often that you find yourself honored and in awe of working with somebody. He’s one of those guys that you go, ‘Golly, even at my age, I hope I grow up to be like Danny King.’”

Musgrove says she was struck, first of all, by statistics on PSJA’s dropout and graduation rates. Looking closer, she was impressed by how thoroughly he’d won the community’s support. “Quite honestly, I think it’s inexcusable that it’s not happening elsewhere,” she says, and she has tried to bring his approach into state policy. In 2013, lawmakers in Austin engaged in a major redesign of Texas’ high school degree requirements, reducing the number of tests and encouraging districts to develop career preparation programs. The new plan, House Bill 5, created a tension: Business groups were pushing for more career and technical classes, while Latino education advocates worried it would prompt a resurgence of “tracking,” steering poor kids away from college and into, say, a chemical factory or a Toyota plant. Musgrove says King’s work in PSJA struck the right balance; the district became a touchstone in the debate over the bill. “We were pretty much at odds with any faction that was dealing with that bill at that point, and absolutely, PSJA was the district that we consistently brought up to show these things don’t have to be mutually exclusive,” she says.

King may not have the big personality of a politician, but he’s been able to get the right people excited about working with his schools.

Ann Beeson, executive director of the Center for Public Policy Priorities in Austin, compares King’s power as an advocate to Geoffrey Canada, the charismatic founder of the Harlem Children’s Zone in New York whose work has inspired many charter school founders and other swing-for-the-fences school reformers. Unlike Canada, though, King doesn’t draw on any obvious stage presence. Instead, Beeson says, “It’s a fierce determination. A fierce, quiet determination. … ‘I’m gonna stand my ground and I’m gonna fix this problem and there’s not anybody that’s going to stop me.’”

On paper, King’s ideas are hardly unique to PSJA. Dual credit has been around since the 1950s. Early education, community outreach, dual language learning — these are all popular in schools today. In PSJA, King has committed to delivering them evenly across the whole district, to as many students as possible.

“Any district can put a glass bell jar over a campus and make it beautiful, get the best teachers and [hand-pick] the kids. … You create a fine arts academy, you bring in your best math and science teachers, and it’s an exciting place, but you’ve drained the regular schools,” says Montemayor. “What is so amazing here is that … they’re saying, ‘This is going to be offered to everybody, and if you don’t want to get a college degree, we want you to at least get a high-level certificate with college credit.’”

The democratic nature of PSJA’s improvement is a big part of what sets King’s work apart. His hope for PSJA is about doing the greatest possible good with the resources that a large public institution can command — a reminder of why we have public school systems in the first place.

PSJA’s work is also noteworthy because King and his team have done so much with so little; Texas public schools are chronically underfunded and much of King’s creativity has been employed to fund his ideas. Extreme budget hawks may be tempted to look at what PSJA has accomplished in such a poor area by hustling for grants, and think its example is an alternative to adequately funding Texas schools. “The danger is to say, ‘If King can do it at PSJA, you can do it,’” says Montemayor. “He is brilliant at putting the money together and using the budget, but he could be doing so much more if there was fair funding.”

Part of the trick has been sharing the work, and the cost, with colleges, technical schools, hospitals, foundations and other partners. King and his staff seem to be constantly searching for the next collaboration that will extend the district’s reach.

“You’ll often hear people say, ‘Well, not every child’s gonna go to college,’” says Ruben Cortez, who represents South Texas on the State Board of Education. “But Danny King’s of the philosophy that, ‘Well, maybe not all of yours are going to college, but I want all of mine to.’”

King likes to talk about the advantages he has working in South Texas. The prevalence of Spanish gives the district a huge opportunity in its dual language program. The Valley’s growth promises more opportunities for educated young people. Pharr’s population roughly doubled in the last 20 years, and there’s far more to the economy now than the agriculture and shipping industries that defined the area for so long. The new University of Texas-Rio Grande Valley opens this fall, consolidating the UT campuses in Brownsville and Edinburg, and a medical school is opening. Among the Valley’s economic boosters, the coming SpaceX launch site near Brownsville has become a token of good things to come. King and other Valley educators hope to seize the moment, so that the new prosperity might reach more than a privileged few.

“I’ve turned down many opportunities to leave the Valley for bigger things,” King says. “Some people might see it as banging my head against a brick wall, but I’ve committed to shaking up the system and doing education different.”

PSJA Deputy Superintendent Narciso Garcia is a King acolyte who drove the rapid expansion of early college at PSJA North High School in King’s first years. On his desk, Garcia keeps a photo of himself as a child in an Indiana tomato field. “I like to share it with staff and students,” he says. “Our goal is not to connect just the top 10 percent with college. It’s to connect everyone, everyone like me.”

King has made early college universal in a district where 89 percent of the students live in poverty and almost half speak limited English.

As a migrant farmworker, he came close to dropping out of school because the days were so exhausting. Although his parents always reminded him of the importance of education, the hours he spent in the fields left little time for schoolwork. When he graduated from high school in Edcouch, about 20 miles from Pharr, Garcia was accepted at UT-Pan American but was shocked to discover that his federal financial aid application was declined; without help from his school, he’d filled out the application wrong. He spent four years in the military instead, which he says is the only way he was able to pay for college.

Sara King, the superintendent’s wife, was also a migrant farmworker as a child, and asked me a rhetorical question that I heard a lot from people explaining the quick growth of early college in the area: “Why not South Texas?” She sees a future in which the Valley is an exporter of skilled labor. “Why can’t we be the area that is producing engineers and welders and teachers and nurses?” she says. “If the whole U.S. needs nurses and the high demand forces us to bring people from other countries, why can’t it be here, and our kids?”

The transformation King has in mind is about both academics and economics. In a fast-growing area with an increasing demand for skilled labor, King is essentially coordinating not just a learning community, but a jobs plan: If finishing a certificate program will make life better for young people and their families, then it’s the school’s job to help them earn those certificates.

If they want to continue their education beyond that, even better. King describes a “stacking” approach, encouraging students to earn one credential on top of another, as far up the ladder as they can go.

“The easiest thing for me to do would be to just be the superintendent and run the school and worry about the state tests and that’s it,” he says. “This kind of work, whether it’s early college or looking at how to engage with the community and seeing if we can accelerate things, it’s really complex work. And I’m sure, when I hang up the hat I’m sure I’m not going to be satisfied and say, ‘Well, we did it.’ Hopefully we will have moved the needle.”

King’s style is quiet and lacking in bombast, but there’s something radical about his approach. He says he’s testing a theory: That providing a high level of education — not only to a few striving children but to an entire community — might be an inoculation against systemic poverty. “We know there’s a correlation. We might not be able to solve that, but we know what we can work on,” King says. “What if we succeed on the educational side? … Will the economic side grow automatically?”

School policy in the No Child Left Behind era, under both Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, tends to treat education as a solvable problem, reform as a search for the answer, and school leaders as sages with a secret to sell. As that era ends, King’s work offers a promising idea of what might come next, or at least how the conversation could change: Schools can be agents of change in their communities, not just targets for improvement from outside.