Studies: Links Between Fracking and Smog Pollution Stronger Than State Claims

Above: Barnett Shale rig

New research suggests that pollution from fracking contributes a much larger share of Dallas-Fort Worth’s smog problem than state officials have said. The study, conducted by Mahdi Ahmadi, a graduate student at the University of North Texas, was presented at a clean-air meeting this morning in Arlington. The Observer received a copy of the presentation.

Ahmadi analyzed data from 16 air-quality monitors in the Metroplex going back to 1997, looking for a connection between oil and gas production and ozone. Seven of the sites were east of Denton, outside of the Barnett Shale, and nine were located in the shale area, close to oil and gas activity.

Ahmadi’s twist is that he adjusted for meteorological conditions, including air temperature, wind speed and sunlight—key ingredients in ozone formation. Backing natural factors out of the data allowed Ahmadi to better pinpoint human factors, including the link between fracking and ozone formation.

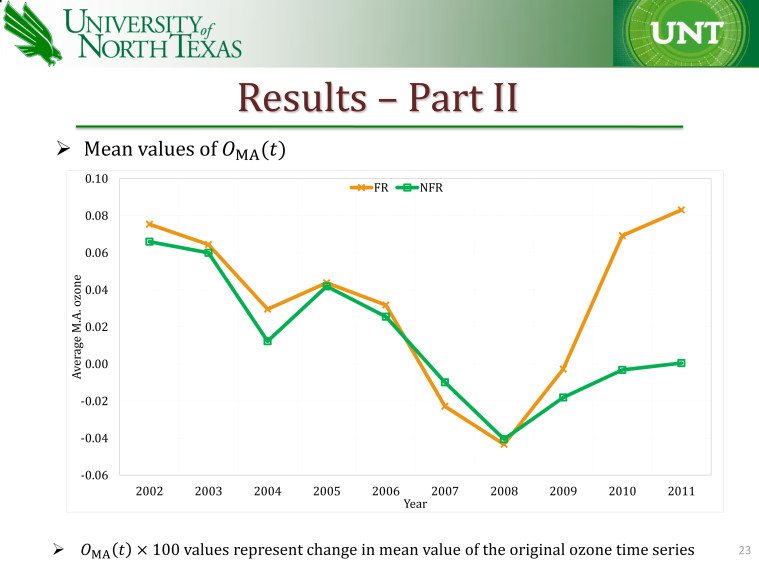

He found that while smog levels have dropped overall since the late 1990s, ozone levels in fracking areas have been increasing steadily and rising at a much higher rate than in areas without oil and gas activity.

“This is a small but important victory for real science in this process, as opposed to the completely politicized approach by TCEQ to prevent the imposition of new controls of any kind,” said Jim Schermbeck, director of North Texas clean-air group Downwinders at Risk.

Since 2008, meteorologically-adjusted ozone in the fracking region has increased 12 percent while in the non-fracking region ozone rose just 4 percent.

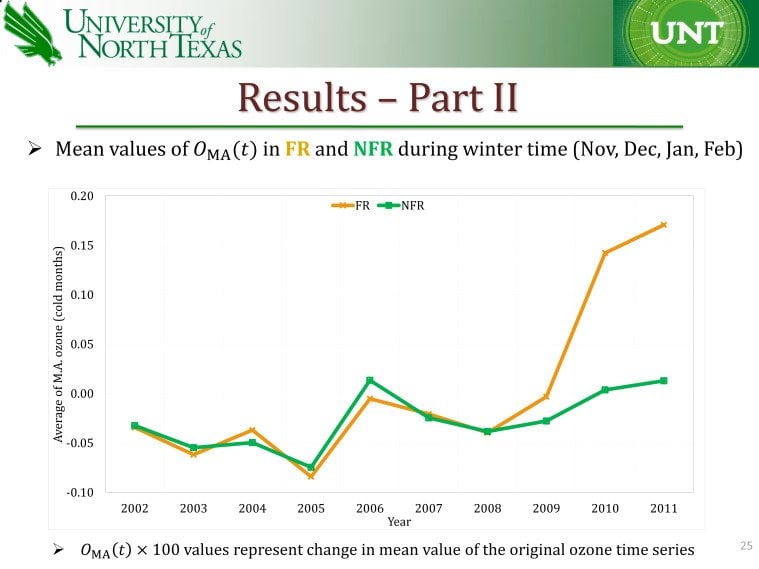

The trend during the winter was “even more striking,” said Dr. Kuruvilla John, the UNT engineering professor who oversaw the study. During winter months, the fracking region saw a 21-percent increase in ozone, while in the non-fracking area it went up 5 percent.

The trend during the winter was “even more striking,” said Dr. Kuruvilla John, the UNT engineering professor who oversaw the study. During winter months, the fracking region saw a 21-percent increase in ozone, while in the non-fracking area it went up 5 percent.

That’s significant because ozone season has traditionally been confined to the summer months. Moreover, EPA’s smog standards have become increasingly stringent over time, as scientists find more evidence for health problems at lower levels. If the EPA were to lower the ozone standard to 60 or 65 parts per billion—it currently sits at 75 ppb—the Dallas-Fort Worth region could find itself out of compliance even during winter months.

Regardless, Ahmadi’s research directly challenges the message from Gov. Rick Perry and Texas’ top environmental officials, who routinely dismiss links between smog, and oil and gas activity. On its website, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality claims that because the wind “blows emissions from the Barnett Shale away from the DFW area,” those emissions from fracking are “not expected to significantly affect ozone in the DFW area.”

The new UNT research isn’t the only recent study suggesting that the state’s scientific understanding of ozone is shaky. A study conducted for the Alamo Area Council of Governments, released earlier this month, found that fracking activity in South Texas’ Eagle Ford Shale would drive large increases in the two main ozone ingredients and imperil San Antonio’s compliance with federal smog rules.

Apparently, the group’s public probing of the fracking-smog links didn’t sit too well with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. The Austin American-Statesman reported on Monday:

“The Texas environmental agency has frozen funding for a San Antonio area governmental coalition’s air quality improvement work after an official there publicly shared modeling results that suggested fracking contributed pollution to the city.

“Last summer the Alamo Area Council of Governments made public a report that found that hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, in the Eagle Ford shale field endangers air quality in the San Antonio area – and, to a milder extent, the Austin area.

“The Alamo group, composed of officials representing local governments over a 12-county area, did not share the report’s data beforehand with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, which had paid for its collection.

“So when it came time last fall to dole out money to councils of government from across the state – including the council from the Austin area – all but the Alamo area council were rewarded with a roughly 30 percent uptick in Legislature-appropriated money to carry out air quality monitoring and planning work.”