Skeptics Gone Wild: Navigating America’s Conspiracy Theory Culture

There’s no longer anything especially irrational about believing that shadowy actors are subverting American democracy.

Above: Members of the Warren Commission present their report on the assassination of President John F. Kennedy to President Lyndon Johnson in the White House Cabinet Room, Washington, D.C.

con·spir·a·cy the·o·ry

noun: conspiracy theory; plural noun: conspiracy theories

1. a belief that some covert but influential organization is responsible for a circumstance or event.

In 1967, the Central Intelligence Agency began to worry about the proliferation of dangerous theories about President Kennedy’s 1963 assassination. The Warren Commission Report, released three years earlier, had concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald, acting alone, killed the president with two of the three shots he fired from the Texas School Book Depository in downtown Dallas.

Anyone with even passing knowledge of the subject will recall that there was much about the Kennedy assassination that was, shall we say, odd. And so the Warren Commission Report, which blamed the whole affair on the unstable (and by then conveniently dead) Oswald, was greeted with widespread skepticism. As much as 46 percent of the American public, according to contemporary polls, doubted that Oswald had acted alone. Some suspected that Oswald had done the bidding of the CIA. Others claimed that Lyndon Johnson, Kennedy’s vice president and successor, had orchestrated the assassination.

Such speculation, CIA agents wrote in Document 1035-960, declassified in 1976 and marked “Concerning Criticism of the Warren Report,” was not only cause for concern to Johnson, the CIA and the members of the Warren Commission, but it also posed a threat to “the whole reputation of the American government.” Even considering such heresies was deemed dangerous. The agency resolved to fight back by “provid[ing] material countering and discrediting the claims of the conspiracy theorists.”

With “conspiracy theorists,” the CIA gave currency to a coinage that until then had been obscure: that American elites might control the political process through extralegal means like assassination. And even as they named it, the CIA moved against it: Document 1035-960 proposed that the agency use “propaganda assets” to discredit conspiracy theorists using newspaper and magazine articles planted with “friendly” editors.

In a sense, the CIA failed miserably. Not only does a majority of the country now believe that the official account of JFK’s assassination is wrong (59 percent, according to a 2013 poll), but we are now living in a golden age of conspiracy theory. According to a recent poll conducted by Fairleigh Dickinson University, 63 percent of registered voters believe in at least one conspiracy theory (though, as we’re going to see, that term is a little problematic). The same poll found that one in four Americans is a so-called Truther, believing that the Bush administration had advance knowledge of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. (Among New York City residents, that number is closer to 50 percent.)

This state of affairs is now, as it was in 1967, quite uncomfortable for some people. Numerous hand-wringing articles try to explain the American affair with conspiracy theory through cognitive bias, civic cynicism and the echo-chamber effect of self-selecting Internet communities.

But trying to explain away anyone’s specific conspiracy belief, or conspiratorial thinking in general, misses the point—the point being that there’s no longer anything especially irrational about believing that shadowy actors are subverting American democracy. Think of that CIA dispatch, advocating a propaganda campaign against the suspicious. Picture the president, slumped forward in the back seat of his limousine, a bullet through his neck. As he lays dying something new is being born, a creeping miasma of suspicion that will spread across Dallas, across Texas, across America.

The trouble with a phrase like “conspiracy theory” is that it’s the rare phrase that can be used both as a neutral description and as a dismissive put-down. In one usage, it describes an allegation that some action was planned by secret plotting: for example, that the Bush administration conspired in 2003 to lead the country into war in Iraq. In the other, it’s straight-up pejorative. To label something a conspiracy theory is to place it beyond the bounds of what rational people are willing to entertain. In the mainstream press, “conspiracy theory” translates as “crazy talk.”

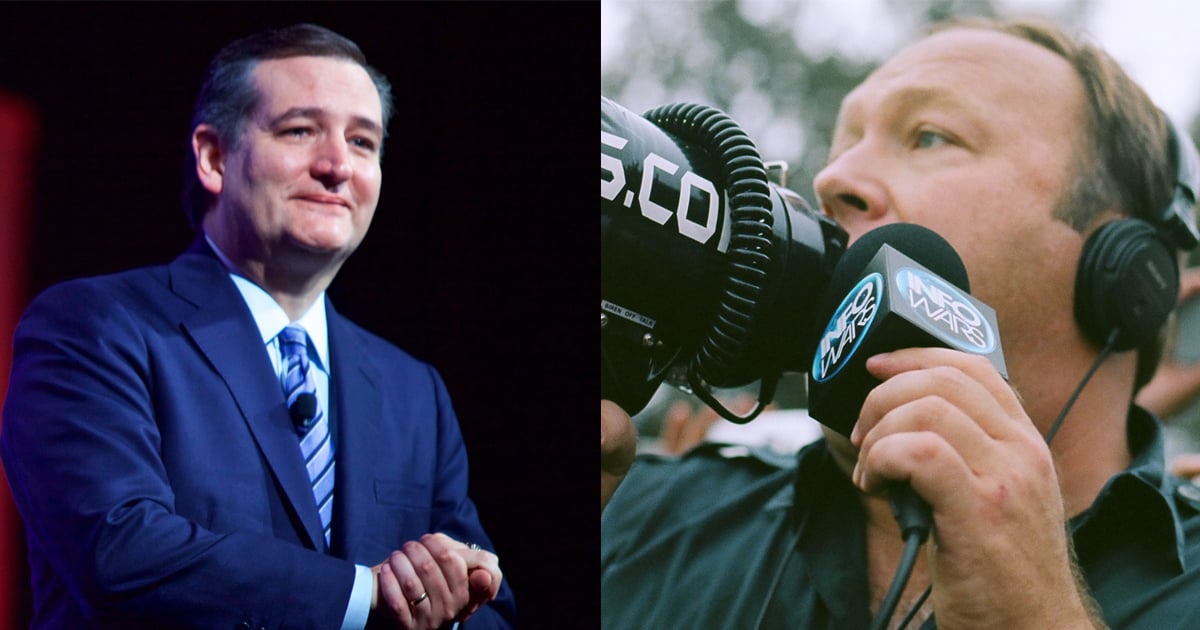

These two meanings are frequently conflated, often by the people who proffer them. Today’s godfather of crazy-talk conspiracy is Texas’ own Alex Jones, a gravel-voiced 39-year-old Austinite who broadcasts daily to around 4 million listeners through his radio program, The Alex Jones Show; his websites Infowars.com, Prisonplanet.tv, and jonesreport.com; and, since last year, his Infowars magazine. Jones is an unabashed and indiscriminate conspiracy theorist. He believes that the Bush administration planned and executed the 9/11 attacks as part of a nefarious drive toward world government. And Jones’ vision of a state that’s willing and able to execute and obscure the murder of almost 3,000 American citizens is at the center of every message he pumps out. After every recent crisis—the Sandy Hook school shootings, the Boston Marathon bombings, the Oklahoma tornadoes—Jones took to the airwaves to tell his audience that the tragedy was not what it seemed. Not a disturbed gunman. Not a radicalized immigrant. Not weather. Instead, in Jones’ view, these were “false flag” attacks, perpetrated by conspirators at the highest levels of U.S. government for hidden purposes.

After the Oklahoma tornadoes, Jones told a caller to The Alex Jones Show, “Of course there’s weather-weapon stuff going on. We had floods in Texas like 15 years ago, killed 30-something people in one night. Turned out it was the Air Force.”

Now there are obviously some logical difficulties at play in these assertions (Occam’s razor, anyone?). And if you’re willing to accept Jones’ claims at face value, there’s little in the way of a floor to keep you from falling even further down the rabbit hole. I had a roommate in college who had an Alex Jones conspiracy theory of his own: that Jones is a plant, mixing discussion of real plots with outright lunacy so as to discredit all of them equally.

But one of the most striking things about Jones’ crazy talk is that when Jones is interviewed in mainstream journalism outlets, as he increasingly is, hosts don’t just dismiss him. They get upset.

Take Jones’ recent appearance on BBC’s Sunday Politics. In the midst of a rant about the Bilderberg Group, one of his favorite bogeymen, Jones explodes: “Listen! I’m here to warn people! This isn’t a game! The U.S. is building FEMA camps! We have an NDAA [National Defense Authorization Act] where they disappear people now! You have this ‘arrest for public safety life in prison!’”

The FEMA camps, in Jonesworld, are concentration camps to which political dissidents will be removed following some manufactured crisis; the 2012 National Defense Authorization Act, in reality, is an Obama administration defense bill that allows the government to indefinitely detain anyone found supporting al-Qaida or the Taliban. I don’t know that either is particularly crazier than the other, but the segment ends with host Andrew Neil looking at Jones with supreme condescension. “You are the worst person I’ve ever interviewed,” Neil says. Staring into the camera, Neil whirls his finger around his ear and says, “We have an idiot on the program today.”

Gawker’s comment on the interview: “Enjoy watching a sad man’s televised delusional rantings as he creeps closer to the brink.”

In a discussion on HuffPost Live, after Jones’ “weather weapon” comment, host Abby Huntsman went from scornful to seriously bothered by the question of why anyone would say anything so awful.

“Why? Does it come down to the money? Is it his way of finding his own, his audience?… Because this is just absurd.”

Huffington Post political correspondent Zach Carter had the answer. “Right. What’s most reprehensible is how he capitalizes on this stuff to make money off it. He has this whole audience of people who are immune to the truth, who want to believe things that are false. So he’s giving them this new thing that is false to believe in.”

This is all pretty perverse. Do people really believe in fringe conspiracy theories because they want to believe things that are false?

A New York Times Magazine article titled “Why Rational People Buy into Conspiracy Theories” comes up with this answer: It helps them deal with feelings of powerlessness, and “It feels good to be the wise old goat in a flock of sheep.” In a 2008 essay on 9/11 Trutherism, legal scholar and Obama confidant Cass Sunstein argues that Truthers can’t figure out what’s real because they only talk to each other, and so they’re never exposed to alternate explanations. His solution to this problem, echoing CIA Document 1035-960, is to “draw their poison,” i.e., to pay government agents to introduce diverse viewpoints onto Truther message boards, or censor them entirely: a secret conspiracy to combat belief in secret conspiracies.

I don’t have any particular love for Alex Jones, but there is something revealing about the need to bring the man up for the sole purpose of putting him down. If you’re inclined to cynicism, an equally good question is: Why would The Huffington Post, or Gawker, or whoever, cover Tornado Trutherism at all if it’s so self-evidently crazy and offensive? Why invite Alex Jones on your show if you don’t want him to be Alex Jones?

Because while the man is deeply wrong on his facts, that’s a different question from whether he’s crazy. I can’t shake the notion that even in his insanity—sincere or staged—there’s a kernel of truth. Jones makes me feel unsettled in the same way that Israelites hearing the apocalyptic rantings of Daniel or Elijah must have felt unsettled. The words are crazy, but the worldview they express is genuinely troubling. We are probably not wrong in the suspicion that we don’t really know what’s going on. Even the most absurd conspiracy theories point at an abyss yawning beneath our feet.

I suspect that the core objections to conspiracy theory are essentially faith-based, rational-sounding apologia that follow from emotion, not the other way around. Take the Truther claim that the Bush administration had a hand in 9/11. What I feel first in response, long before reasoned argument, is deep offense. It hurts to think about. Only afterward do the reasons come: No, they could never have kept it secret; we would have found out. But these are merely justifications for how I feel.

America is an irrational place, a country built on idealism and myth. For a long time, one of our most treasured myths has been that “it”—the appalling tragedies and incomprehensible inadequacies that afflict the rest of the world—can’t happen here. We are taught this in school just as we are taught not to pick our noses in public. The belief is woven into the fabric of what we grow up to recognize as civilized American life.

Even as we are inculcated with this sense of American exceptionalism, we are also learning about the rest of the world and about history, in which questions of power were and are answered by naked force. We learn about plots and coups, about popular reformers killed with right-wing knives and bullets, about powerful men and women subverting democracy for their own ends.

But not here. Even if no one ever tells us explicitly, we learn that America is different. Our system is immune to such subversions.

We learn this despite the fact that ever since JFK died in Dallas, the American system has been rife with examples of powerful people co-opting it for their own purposes. The Joint Chiefs of Staff really did propose to Kennedy, in 1962, a series of “false flag” terrorist attacks against American citizens to provoke a war with Cuba. In 1964 Lyndon Johnson really did lie to Congress, saying that the North Vietnamese had attacked American ships in the Gulf of Tonkin. Richard Nixon, leading up to the 1968 election, really did promise the North Vietnamese that if they dropped out of peace talks with the South he’d get them a better deal. It wasn’t Nixon’s last attempt at stealing an election.

These allegations are well documented. So is candidate Reagan’s alleged pre-election promise to the Islamist students who had taken 52 American hostages in Iran: that if they didn’t give President Carter the hostages, Reagan would sell them weapons to fight Iraq. We know, too, that after Congress refused the Reagan administration money to depose Nicaragua’s democratically elected government, the administration took the dirty money from weapons sales to Iran and funneled it to Nicaraguan rebels themselves.

There is a strange void in the official conversation about these facts. Every article I’ve read on conspiracy theory at some point nods toward Watergate and Iran-Contra to say, yes, there are real conspiracies. And then the issue is dropped.

“We confirm things like the Gulf of Tonkin,” says Florida State University historian Lance deHaven-Smith, “and it’s in the news one day, and it never gets any further coverage. It comes out later, and people don’t go back and rethink their view of history.”

DeHaven-Smith is the author of Conspiracy Theory in America, a new history of possible executive high crimes in America published by the University of Texas Press. He got interested in the subject after writing a book about the disputed Bush-Gore election in Florida, and started looking for research on high-level corruption in American politics. He figured that with so many well-documented examples, there would be studies. He found nothing. Studies of police involvement with organized crime, yes. Studies of the politics of scandal in Iran-Contra and Watergate, yes. But that was it. No conclusions, no analysis of patterns.

This lack of study has serious consequences for our democracy. We know, for example, that the Bush administration came to power in a questionable election, lied about Iraq, blew Valerie Plame’s cover and built an illegal worldwide network of kidnapping, detention and torture. And yet the idea that this same administration may have had advance knowledge of 9/11 is, in polite discussion, beyond the pale.

“Unless you can ask the question, you can never interrogate the policy, the war on terror, the policymakers, the policy leaders,” deHaven-Smith told me in an interview. “If you have to accept what the government says about it, if you can’t interrogate that narrative, you’re locked into a war on terror. And a lot more than that: a national surveillance state, the consequences of which are profound. Not saying that it’s an inside job, but there’s some questions about this.”

In Conspiracy Theory, deHaven-Smith argues that this reluctance to question power is a relatively new phenomenon. It began, he writes, around the time of the Kennedy assassination, and inaugurated a new era in American political life.

Throughout most of American history, large swaths of the American press and political establishment have been extremely suspicious of the government. DeHaven-Smith argues that America was founded, in fact, on conspiracy theory: the Founders’ fear, described in the Declaration of Independence, that King George III would crush the colonies’ fledgling democracy and institute a despotism.

(Similarly—though deHaven-Smith doesn’t make this point—Texas’ War of Independence can be read as the result of dueling conspiracy theories: the Texan fear that Santa Anna would take away their liberties, and the Mexican fear that Texans wanted to split Texas from Mexico and join the United States.)

But after Kennedy’s death, and CIA Document 1035-960 advocating propaganda war against “conspiracy theorists,” something changed. A new figure entered the American political arena: the conspiracy crazy. In subsequent years, as American foreign policy became ever more bipartisan in its expansionism and militarism, as presidents stopped standing up to the military, as scandals broke at the highest levels, the term “conspiracy theory” appeared more and more in the nation’s leading newspapers. By the mid-1970s it was appearing in 20 to 30 New York Times stories a year, having acquired its current connotation of foolish speculation and unhinged paranoia.

DeHaven-Smith thinks the phrase “conspiracy theory” itself has made it virtually impossible to talk about high crimes by America’s elite.

He calls it the conspiracy-theory conspiracy theory. “I think the political class has a stake in the legitimacy of the system. They don’t allow these things to be discussed.”

Lack of discussion doesn’t make anything go away. Without light shining into the dark places in our national psyche, into our history, dark things grow there.

When I hear Alex Jones talking about weaponized tornadoes and FEMA camps, when I hear tea party mutterings about Obama’s plan to buy up all the bullets, I think of the most dyed-in-the-wool conspiracy theorist I’ve ever met, a college acquaintance named Jeremiah, like the Old Testament prophet. Jeremiah believed in every conspiracy theory I’d ever heard of, and many I hadn’t. He had melded them all into one grand anti-establishment narrative. He was one of the only people I’ve ever known who believed in the lizard-people conspiracy theory: that a race of evil aliens from the planet Nibiru, dressed as humans, controls events on earth.

One day, I remember, he was talking about a theory that the Queen of England has to bathe daily in the blood of aboriginal children, I guess to keep her lizard skin smooth.

This was too much. “Oh for God’s sake, Jeremiah,” I said. “Come on.”

He looked at me. He half-smiled. “Look,” he said. “I’m not saying they are lizard people. I’m just saying that for all they care about us, they might as well be lizard people.”

This, now, is a lens I can’t escape. Was the West fertilizer plant destroyed by missile? Might as well have been. Is President Obama recording my phone call? Might as well be. Are shadowy figures manipulating the world economy for personal gain at my expense? Might as well be.

This is not, I know, a healthy habit. It leaves me—it leaves all of us—open to manipulation by men willing to peddle crazy. Think of David Dewhurst blaming the Texas media for riling up pro-choicers during Wendy Davis’ epic filibuster. Take Louie Gohmert accusing Barack Obama of being in league with the Muslim Brotherhood (claims that are even now being used as propaganda by the Egyptian military). Think of the goddamn Birthers.

And yet I can’t help myself. I think we know, we members of the neglected commons, that something is wrong. This knowledge fuels the inchoate rage that launched the Occupy movement and the tea party. Consider their rants not as literally truth, but as reflective of a paradigm describing the vast asymmetry in power and accountability between the powers that be and the rest of us. Not science or satire, but dark poetry.

Contributing writer Saul Elbein is a freelance journalist in Austin.