UPDATED: Air Pollution from Fracking in Eagle Ford Shale Threatens Health, Report Claims

Updated below with comments from TCEQ

Unlike North Texas’ Barnett Shale play, South Texas’ Eagle Ford fracking bonanza has never received the close scrutiny of fracking skeptics, researchers and regulators. Part of that is because Eagle Ford production didn’t really take off until 2011. It’s also much more sparsely populated than some of the fast-growing parts of the Barnett Shale, especially around Fort Worth and Denton. And, frankly, a lot of people are getting oil-rich from leases or work in the oilfield making decent pay.

A new 47-page report from Earthworks, released this morning, takes a sobering look at the potential health risks from fracking-related air pollution in Karnes County, one of the epicenters of the Eagle Ford Shale. The title offers a sense of its findings: “Reckless Endangerment While Fracking the Eagle Ford: Government Fails, Public Health Suffers and Industry Profits from the Shale Oil Boom.”

“At this point you have to ask the question: Are the regulators only there to create the perception of regulation so the oil and gas industry can do whatever it wants?” said Earthworks spokesperson Alan Septoff.

Drawing on a mixture of government documents, direct air testing and the stories of people in the shale, Earthworks concludes that “air pollution from oil and gas development in the Eagle Ford Shale definitely threatens, and likely harms, the health of Karnes County Texas residents.”

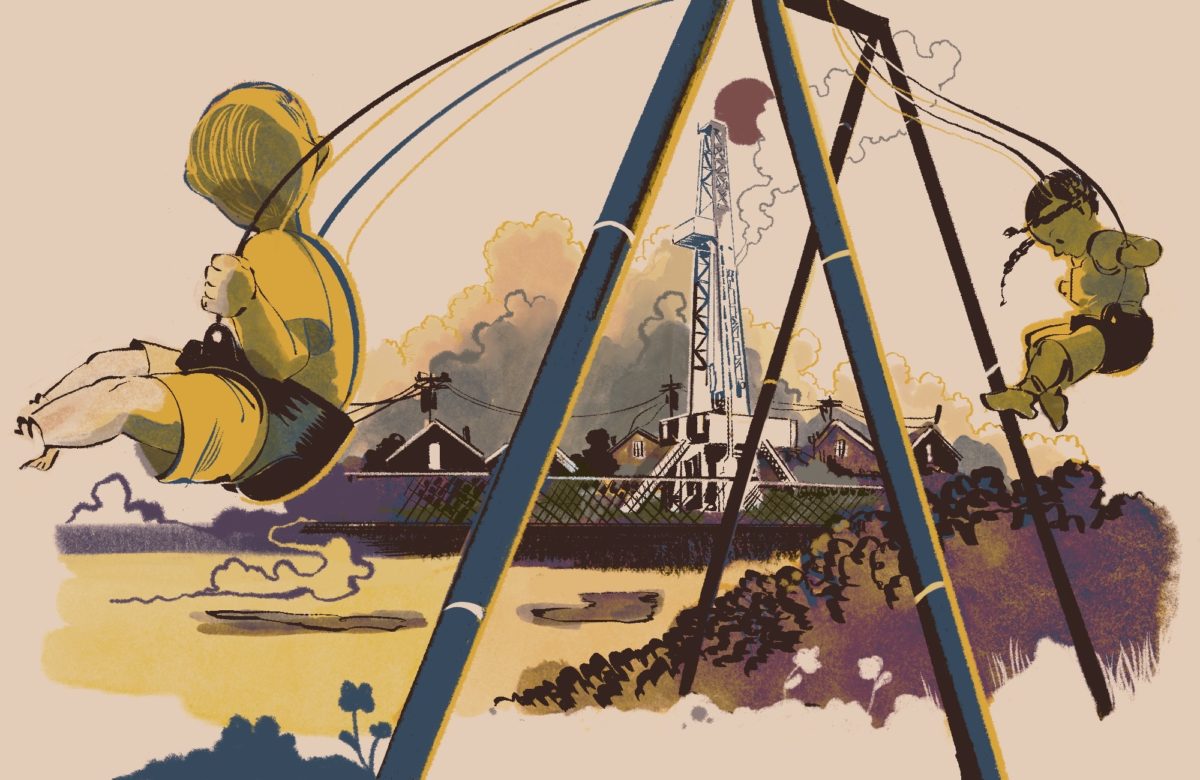

The report focuses on one family in particular as a sort-of case study: the Cernys of Karnes County. Their country home is within two miles of 37 oil and gas facilities, 18 of which have been drilled and fracked within a mile of their house since November 2010. The Cernys, including their 15-year-old son, complain of fatigue, nasal irritation, throat problems, burning eyes, joint pain, severe headaches, dry eyes, nosebleeds and other health problems they associate with emissions from nearby oil and gas activity.

In their research, the Earthworks team discovered that investigators from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality had documented high, even dangerous levels, of pollutants emanating from nearby facilities.

For example, in 2012, TCEQ inspectors visited the Sugarhorn Central Facility, a site operated by Marathon Oil about 1.3 miles from the Cerny home, four times. On two occasions, inspectors with handheld detectors found concentrations of volatile organic compounds—a class of chemicals that includes the carcinogen benzene—that would normally lead to collecting canister samples to be sent to a lab for further testing. But, instead, the state inspectors deemed the levels “too high to safely obtain the samples.”

On another occasion, in August 2012, inspectors wielding an infrared camera happened to catch emissions pluming out of storage tanks at the same site. More than three months later, the company finally filed a report with TCEQ on what happened. The tanks had been venting volatile organic chemicals—which includes benzene and toluene—at 514 times the maximum allowable rate, and hydrogen sulfide at 112 times the allowable rate In August and September 2012, the site had emitted about 69 pounds of benzene, according to the company’s filing.

Although TCEQ issued violation notices to Marathon for exceeding its air permit and not reporting the incident within 24 hours, no fine or penalty was ever levied by the agency.

In a statement, TCEQ said it had collected “several millions of data points for volatile organic compounds” in the Barnett and Eagle Ford Shale plays. “Overall, the monitoring data provide evidence that shale play activity does not significantly impact air quality or pose a threat to human health.”

At another Marathon site, a little over a mile from the Cerny home and even closer to other residences, inspectors detected VOC concentrations of 1,100 parts per million. “The Recon team evacuated the area quickly to prevent exposure,” a report from TCEQ stated. “This facility is less than a mile from Complainant’s residence.”

Were the Cernys or their neighbors in danger of being exposed to unhealthy levels of pollution? There’s really no way of knowing, the report points out. “It is extremely troubling that there is apparently no step taken to either warn nearby residents of the chemicals in the air,” it states, “or to take canister samples at nearby receptors in order to try to determine residents’ potential exposure to the chemicals emanating from the facilities.”

TCEQ criticized Earthworks’ account as incomplete. “[T]heir report does not point out that Marathon personnel were contacted and made aware of the [TCEQ] team’s findings” and the leaking valve was fixed the same day, an agency statement said. TCEQ did not address why its inspectors apparently did not notify nearby residents or take canister samples.

The agency also defended its enforcement record in the Eagle Ford Shale, noting that it has issued 187 notices of violation in the area since September 2010, and launched 408 investigations in the last year.

“The TCEQ has a vigorous, effective enforcement operation in the Eagle Ford Shale, and when problems are detected, the TCEQ makes sure they are rapidly fixed,” TCEQ wrote in a statement.

Earthworks conducted its own on-the-ground investigation, using infrared cameras and canister samples taken from the Cernys’ property an a nearby drilling site. The air testing found that VOCs at the Cerny home were well below levels that TCEQ considers to be of concern. At the drilling site, benzene levels were 20 times TCEQ’s acceptable long-term “air monitoring comparison value.”

In March, Earthworks also drove around Karnes County with an infrared camera of the type state environmental investigators use. The group claims to have documented “numerous emissions” from facilities, including evidence of a broken flare at a Marathon facility first flagged by TCEQ in September.

The report doesn’t, and perhaps can’t, establish a direct, irrefutable link between the Cernys’ health problems and the oil and gas activity in their area. But it does call attention to the severe limitations in Texas’ oversight system. As Earthworks points out, TCEQ has established a network of 24/7 air monitors in the Barnett Shale, providing at least some real-time data to citizens concerned about fracking-related air pollution. No such system is in place in South Texas, although the agency apparently has plans for one monitor in Wilson County, southeast of San Antonio. It’s all little comfort for the Cernys.

“This isn’t living anymore. It’s just existing, and wondering what you are going to breathe in next,” Mike Cerny is quoted as saying in the report.