TEA Takeover Uncertain for Struggling Border District

For the public school community in the South Texas town of Progreso, 2015 ended with the news that the Texas Education Agency was moving ahead with plans to take over the school district.

Outgoing Education Commissioner Michael Williams’ decision to replace the elected school board with five hand-picked managers was the next step in a process that began almost three years earlier with a public corruption investigation into the district’s former superintendent and former board members, who’d been steering school money to preferred contractors. The news of the takeover earlier this month followed a script similar to other recent takeovers in Houston’s North Forest ISD, El Paso ISD and Beaumont ISD, with months of escalation in formal correspondence and administrative hearings.

But unlike those districts, Progreso ISD was already engaged in a separate lawsuit against the state concerning student residency requirements, with millions of dollars at stake, when the state decided to take it over. Thanks to that impending takeover, the state was in a position to end its legal troubles with Progreso ISD simply by replacing the school district’s board with a more deferential board of managers.

“I don’t like to accuse people of retaliation,” says Darren Gibson, an Austin attorney representing Progreso ISD, “but the timing is very suspicious. It certainly calls into question why TEA feels they need to put in a board of managers and displace the democratically elected board of trustees due to the actions of people who haven’t been in place for more than a year and a half.”

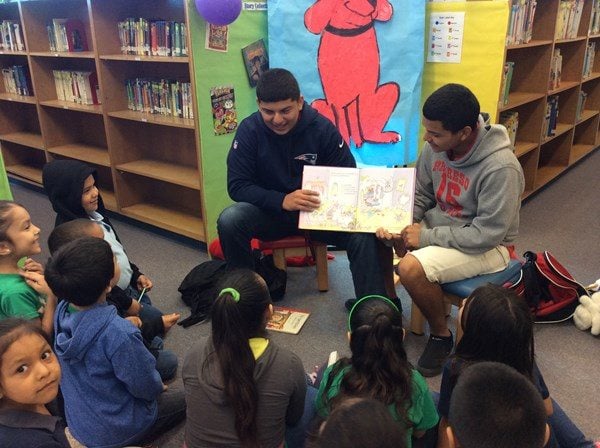

Progreso voters have replaced five of the district’s seven board members since the FBI began investigating the district in 2013, and the new board hired a new superintendent, Martin Cuellar, in July. The small district has also been working with state conservators to make internal improvements; many of its new board members ran on promises of reform. But in the last few months, TEA has said the district’s new board members are too inexperienced — two of them are still in college — and the board’s new choice of superintendent is underqualified for the job. In September, some Progreso residents told the San Antonio Express-News that corruption was still a problem under the new administration.

But Gibson sees a connection between TEA’s takeover plans and a separate legal fight between the district and the state over students’ residency claims. TEA has claimed that Progreso ISD, under its former administration, was allowing Mexican residents into the district in order to pad its enrollment and claim thousands more each year in funding from the state. The district sued TEA in March 2015 to reclaim funding the state had withheld, and the two have been locked in a court fight ever since.

“I don’t like to accuse people of retaliation, but the timing is very suspicious.”

That lawsuit appeared to be nearing its end early this year, Gibson says. According to emails Gibson shared with the Observer, on January 4 Assistant Attorney General Karen Watkins agreed to a mediation date with the district later in the month. Referencing the state-appointed board announced days earlier, she wrote that she hoped the district’s “new decision-makers” would have time to get acquainted with the case before then.

Early the following day, the district won a temporary restraining order to keep the board of managers from taking over. Later that night, Watkins wrote again to cancel the mediation date. Noting the “substantial uncertainty” about who would be calling the shots for Progreso ISD by the time the mediation came around, she suggested it would be better to wait.

To Gibson, the timing suggests that TEA wasn’t interested in negotiating an end to the residency lawsuit without knowing that “their own board of managers are in place to control the resolution of this litigation,” he says. “The moment we got our TRO, they said they refused to mediate. I can’t imagine much clearer connection.”

The district’s hearing with the state is set in Austin on January 19, to determine whether the district can continue holding off the state’s takeover.