In a Do-Nothing Congress, Blake Farenthold is Enjoying the View

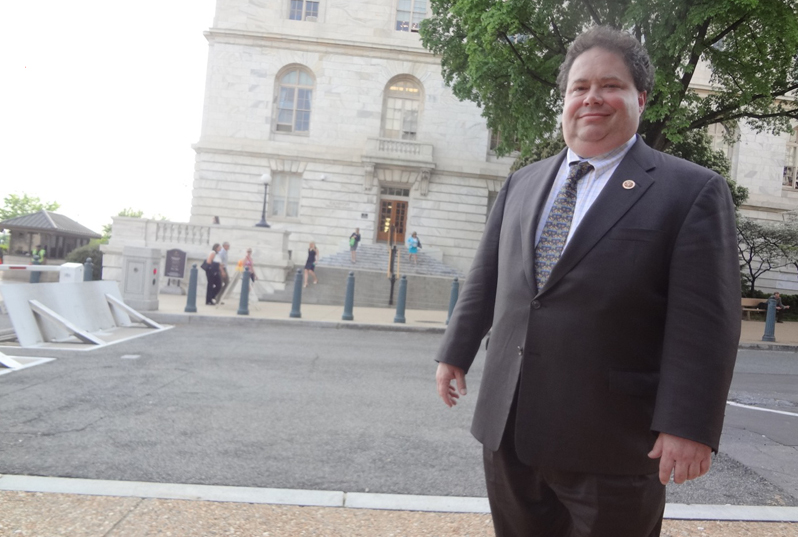

Blake Farenthold, the tea party congressman from Corpus Christi, has settled into a routine where distraction is just part of the job.

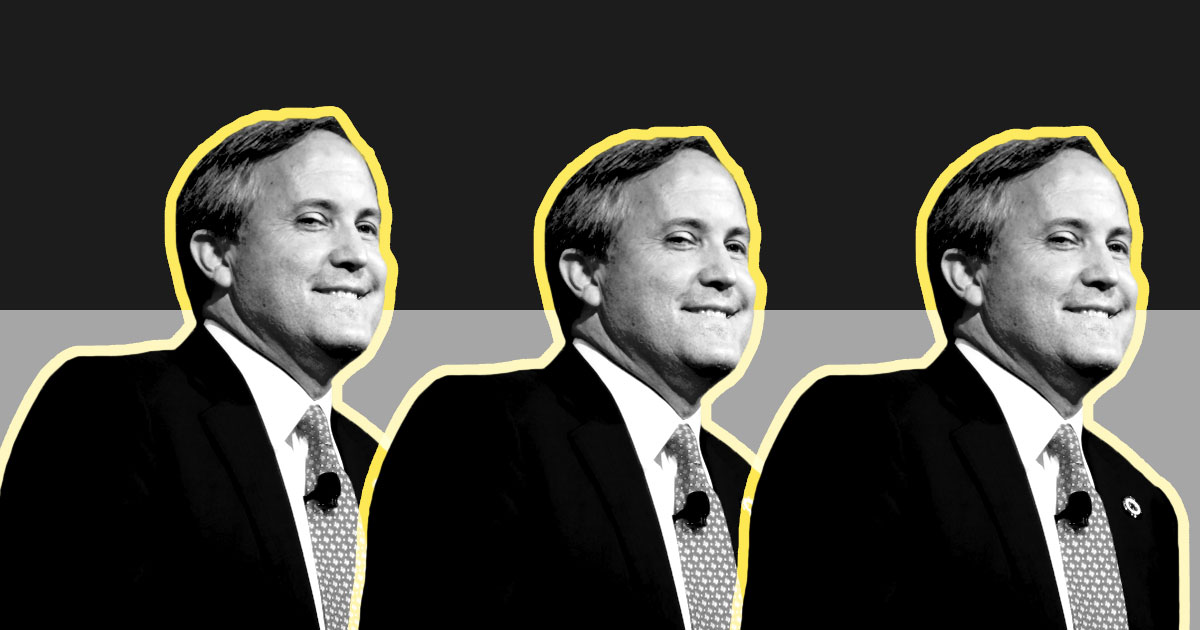

Above: Congressman Blake Farenthold

It’s 5:45 p.m. on a muggy, late spring Thursday evening in Washington, D.C. and Texas Congressman Blake Farenthold is making the 300-yard walk from the National Republican Club of Capitol Hill to the Capitol for a vote.

We’ve just finished a half-hour interview in a dimly lit room in a subterranean level of the club. I’d been following him on social media but wanted to go beyond the tweets to see how a tea party outsider, who’d left his comfortable life in Corpus Christi four years ago, had made the transition to incumbent lawmaker.

Farenthold was making the trek to the House to vote “yes” on House Resolution 567—”Providing for the Establishment of the Select Committee on the Events Surrounding the 2012 Terrorist Attack in Benghazi.”

“Benghazi”—as the attacks on the U.S. diplomatic mission in Libya have come to be known—is an almost all-consuming issue for congressional Republicans these days, and the special committee created by that legislation should keep the fires of outrage and accusation stoked at least through November.

That he’s taking a vote at all is remarkable. As of mid-June, the 113th Congress had only enacted 121 laws, far below the average of the last 30 years and a figure that puts this Congress on track to pass the fewest number of bills in history.

For congressmen like Farenthold, a conservative Republican and member of the House Tea Party Caucus, lawmaking is largely a sideshow. Farenthold came in on the tea party wave of 2010, edging the Democratic incumbent by a mere 800 votes. Gerrymandering by the Texas Legislature gave him a much more Republican district to run in and he coasted in 2012 with 57 percent of the vote. This year, his Democratic opponent is not expected to pose much of a challenge.

Now in his second term serving Texas’ 27th District—a large scrap of South Texas that ranges from Farenthold’s hometown of Corpus Christi up the coast toward Houston—Farenthold has settled into a routine where distraction is just part of the job.

In four years, Farenthold has passed one bill and if he’s known outside his district—where more than one out of five lacks health insurance and 23 percent of kids live in poverty—it’s probably because Bill Maher recently made him the target of his “Flip a District” segment. Farenthold’s other notable turn in the national spotlight: When he first ran for office in 2010, a photo surfaced of the future congressman wearing ducky pajamas and grinning ear to ear with his arm draped around a buxom woman. He’s also flirted with “birther-ism”—the notion that President Obama isn’t a U.S. citizen—and called for Obama’s impeachment.

An avid user of social media, Farenthold’s Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and Foursquare accounts chronicle the life of a tea party congressman in a do-nothing Congress. Here’s a photo of his leather loafers and the cramped seating on the plane back to Corpus Christi, where he returns almost every weekend. Here he is at Pete’s Dueling Piano Bar in Fort Worth during the Texas GOP Convention. Or the China Garden Super Buffett in Corpus Christi. “Mhbvhmkkbjngrvyhc,” he inadvertently wrote on Foursquare. “Bhnhxbg*sqt.” Frequent late-night visits to bars on the campaign trail in 2010 earned him the “Crunked” and “Bender” badges on Foursquare.

But Farenthold, who co-hosted a Corpus right-wing radio show before running for Congress, loves the job.

“If you look at what I’ve done in my life it’s like God was preparing me to run for office and be a congressman but I didn’t know it,” said Farenthold. He said his work in radio taught him how to communicate with the public, his time as a lawyer how to draft legislation, and his computer consulting business how to deal with the issues of signing the front of the check rather than the back. It was less clear what his time in Congress is preparing him for.

“The line I use at home is I don’t stay up here long enough for the stupid to rub off on me,” said Farenthold, who is stout and wide chested with dark curly hair that has acquired a congressional grey wisp, during our interview in the Republican Club. “That usually gets a chuckle.”

Of course, Farenthold is hardly alone in his itinerancy. U.S. Rep. Joaquín Castro (D-San Antonio), recently lamented to the Observer that he spends more time on airplanes than on the House floor. But Farenthold doesn’t complain.

“The travel was a pain in the butt until I realized this is the one time when there’s no telephone ringing,” he said. “Once I claimed the travel time as my own I can now download a movie or some TV shows to watch on my iPad. Now I actually look forward to getting on the airplane.”

Once Farenthold deplanes, there’s no shortage of demands needing attention in his district of nearly 700,000 residents. Corpus Christi is a major international trade hub, servicing the booming Eagle Ford Shale region. His district is nearly half Hispanic and the border is just a few hours’ drive. There are sensitive wetlands and polluting petrochemical refineries, not to mention persistently high pockets of poverty and the ever-present threat of hurricanes.

And then there’s getting a chuckle from constituents, another priority. Farenthold manages his own social media accounts which provide an outlet for his many humorous sallies. A recent Instagram photo shows him scowling alongside two other congressmen. The photo is captioned “#regram Not my best look but I do have cool #amigos on @HouseJudiciaryCommittee.”

He’s also posted selfies with Texas Gov. Rick Perry and shown himself eating ice cream with fellow House Republican Darrell Issa. He’s done some entertaining Amazon.com reviews—though only one since joining Congress—including for earphones, a bartending book, a Jimmy Buffet album and a mango splitter:

“I love mangos and hate preparing them, so I figured it was worth a gamble on this. Wow! Much to my surprise it works like a charm, making slicing mangos a breeze even for breakfast at 5:00am.”

When not entertaining his followers, Farenthold’s main concern is that an “overzealous” federal government will stifle growth in his district, which is endowed with significant oil and gas deposits newly accessible through fracking in the Eagle Ford Shale. Farenthold wants to expedite the permitting of new liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals that would export Texas’ cheap natural gas abroad.

His district is home to one of the largest concentrations of petrochemical refineries in the nation as well as thousands of square miles of beaches, ecologically-rich estuaries and the endangered whooping crane.

Farenthold addressed environmental concerns in passing, saying “we’ve got to protect the environment and we’ve got to be safe, but let’s set the goal posts and allow the companies to meet them and not change the rules in the middle.”

He also recently signed a letter from 29 Texans in Congress to EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy opposing the agency’s planned regulation of carbon dioxide from existing power plants. In the past Farenthold has called climate change a “scare tactic used by groups with a political agenda.”

Farenthold has politics in his blood but not the kind you would expect. His step-grandmother, his grandfather’s second wife, Frances Tarlton “Sissy” Farenthold, was the only women in the 1968 Texas House of Representatives and co-sponsored, with Barbara Jordan, the Equal Legal Rights Amendment to the Texas Constitution. She went on to run for Texas governor twice as a progressive Democrat.

Farenthold’s family on both sides has prospered in Texas for generations. His great-grandfather, Rand Morgan, made money in farming, ranching and the oil business in South Texas. According to Roll Call, Farenthold is the 39th wealthiest member of Congress, with assets of $8.5 million. The Center for Responsive Politics, a Washington, D.C.-based research group, has estimated that if Farenthold’s family businesses and trusts are included, he’s worth about $35 million. A Corpus Christi airport terminal is named after Farenthold’s stepfather, Hayden Head, Sr., a partner at Kleberg Law Firm, where Farenthold spent seven years on his path to becoming a Congressman.

In contrast, the average per capita income is about $24,000 in his district, with about 16 percent living below the poverty line.

When it comes to immigration reform, Farenthold faces quite a dilemma. As a tea partier, he must take care not to anger the anti-amnesty crowd, but he represents a district that is more than half Hispanic and sits on the House Judiciary Committee, which has effectively bottled up immigration-related legislation.

In an interview after a town hall last summer in Gonzales, Texas, Farenthold outlined his approach to negotiations. “My deal is you start as far to the right as you can get, and go to the conference committee with the Senate, and hopefully end up with something you can live with. Getting to citizenship is going to be tough, but never say never.”

He’s also talked about a “compassionate solution” that gives undocumented youths brought to the country by their parents, or DREAMers, a pathway to citizenship while their parents get deported. But last year he voted to restart deportation of DREAMers after President Obama signed an executive order giving some undocumented youth a temporary reprieve from deportation.

With immigration reform at a congressional standstill, Farenthold’s attention on the House Judiciary Committee is fixed on a new pet project—trying to force the resignation of Attorney General Eric Holder over the Fast and Furious program, a federal gun-tracking effort that went awry.

Last year Farenthold joined a contingent of hardline Republicans in an effort to impeach Holder. Since then, he’s introduced legislation prohibiting federal employees found in contempt of Congress from receiving government paychecks.

Farenthold has sponsored 18 bills and has had one signed into law—the OPM IG Act, which authorizes the the inspector general in the Office of Personnel Management to use a revolving fund for audits and investigations.

In May he introduced a bill calling for the removal of a part of Mustang Island, a barrier island in his his district, from the Coastal Barrier Resources System (CBRS), which restricts development on protected coastal areas that serve as buffers to storms and important ecological zones. Areas in the coastal system can’t receive federally-subsidized flood insurance through the controversial National Flood Insurance Program, including Tortuga Dunes, an “ultra-luxury, master-planned community” under development on Mustang Island.

Farenthold doesn’t have a deep policy background, but he knows the ins and outs of the media. He studied Radio, Television and Film at UT-Austin in the early 1980s, during which time he was a radio DJ, and co-hosted Lago in the Morning, a conservative talk radio program in Corpus, until he began his political career.

“Working in radio taught me not to be afraid of a microphone or getting in front of the camera,” he said. “It also helped me understand how to shorten answers to where they fit into sound bites.”

He went on to say he doesn’t want to be “one of those people who die in office,” but will probably stick around for about a decade. “If you look at my history I typically last about 10 years at a job then I feel like I’ve mastered it and go on.”

Having eaten only a few bites of the popcorn he ordered, Farenthold’s communications director, who he called “the hardest working person on his staff,” told him it was time to head back to the Capitol. As we emerged into the lobby of the Republican Club, Farenthold barely broke stride shaking hands with several back-patting congressmen as he left the club for the short walk to the Capitol. After the Benghazi vote he would head back to Texas for the weekend, but only after admiring the view. D.C.’s famous cherry blossom season had recently passed, and the majestic mall was littered with wilted flower petals that tourists navigated around. At the other end, Farenthold could see the Washington Monument, recently reopened after a three-year repair job.

“There’s nothing like walking out of the Capitol and down the Capitol steps and looking at the Supreme Court and the Library of Congress,” said Farenthold. “I will stop regularly and take a picture.”

He still seems amazed to be here at all.