Lessons Unlearned

Long before the Legislature made vaccines optional, Texans united to fight polio.

As the nation obsesses over whether swine flu will eventually mutate into an unstoppable pandemic, a germ from the past has been making an unlikely comeback in the Lone Star State—pertussis, or whooping cough. The disease is highly contagious, usually infects children and can be deadly for infants. Oddly enough, there’s a childhood vaccine that offers immunity from whooping cough. After it went into widespread use in the 1940s, whooping cough infections almost disappeared. As recently as 2003, there were only 670 cases in all of Texas. But something happened between then and 2009, when more than 2,000 Texans, mostly children, came down with the disease. What could cause a long-dormant illness to come back so fiercely?

Here’s one possibility. In 2003, Gov. Rick Perry signed a state law that allows parents to opt out of vaccination programs for reasons of “conscience,” including religion or any other rationale. The law is a response to a number of vocal parents who have become convinced that vaccines are responsible for the dramatic rise in autism cases over the past decade—despite the fact that several large, peer-reviewed studies have found no evidence that this is the case. According to data from the Texas Department of State Health Services, in 2003, parents of 2,314 children applied for an exemption. By the end of 2009, the total had reached beyond 12,600.

These parents believe that since the majority of children are vaccinated, their kids are safe. But the whooping cough statistics show that dormant diseases can still find a foothold. And diseases that we don’t worry much about anymore—like polio—still thrive in other parts of the world. The success of the anti-vaccine movement shows just how quickly and powerfully rumors and false information can spread on the Internet. It’s also a great example of how short our memories are. Ironically, the success of vaccines has convinced parents they don’t need them.

Texas doesn’t have to look very far into its past to find a time when a vaccine was considered a godsend. No other state was hit as hard by the polio outbreak of the 1940s and early ’50s. Anti-vaccine advocates would not have found many followers in Texas at that time, when public officials, celebrities and ordinary people came together to fund a desperately needed vaccine.

Poliomyelitis is a hand-to-mouth disease ingested from unwashed hands or contaminated objects. For many years, the disease was called “infantile paralysis” because it affected mainly children. As polio epidemics escalated, newspapers shortened the term to “polio” to fit headlines.

During the first half of the 20th century, every parent and child feared polio. It attacked male and female, black and white, from rural communities to suburbia. Most people understood that a virus caused polio, but no one knew where the virus came from or how victims would fare. Often, the virus entered the body, created mild, flu-like symptoms, and left it virtually unscathed. At other times, the disease caused permanent deformity, weeks or a lifetime in the fearsome iron lung, or death. Certain aspects of polio everyone knew: It was highly contagious; it struck without warning and preferred children and young adults; it had no preventative or cure.

Polio raged across Texas. Between 1942 and 1955, major polio outbreaks occurred every year in the state, affecting thousands of families each time. The outbreaks touched every region, from Amarillo to the Rio Grande Valley and points east and west. Houston and surrounding Harris County suffered the most. From 1943 to 1954, Harris County endured an epidemic every other year, compiling one-fifth to one-fourth of state infections. No other county in the nation except for Los Angeles experienced polio epidemics with such frightening regularity.

The random nature of polio haunted everyone. The disease could strike one individual in a neighborhood or paralyze several. One child could experience a mild case while a playmate became paralyzed and required an iron lung. During the 1948 epidemic, a Houston man likened the randomness to a “flier over a target with flak popping all around. You don’t know who’s next.” As a child living in Odessa, Enola Gay Mathews remembers being terrified that polio would strike while she slept. “I remember sleeping in a tight ball,” recalls Mathews, “and the first thing I did when I woke up was to check and see if my arms and legs worked.”

Each onslaught of polio was met with confusion and dread. Without a precise way to stop it, Texas communities implemented a variety of means to prevent outbreaks. Churches canceled weekly services. Swimming pools closed. Theater marquees went dark. Airplanes spread DDT from North Texas to Galveston Bay. Newspapers issued daily tallies of polio cases, complete with the victims’ names and addresses. During the 1949 San Angelo epidemic, motorists drove through the sweltering, dusty city with windows rolled up and avoided putting air in their tires for fear of taking the virus with them. Many people avoided telephone conversations for fear that polio transferred across phone lines.

The anxious atmosphere in Texas hospitals paralleled the panic and uncertainty of the world outside. Physicians and nurses operated under the terror of contracting polio or, worse, taking the disease home with them. As patients struggled through polio’s acute state, physicians often distanced themselves from their charges, standing in doorways or making observations through a glass partition. This fear was not unfounded. During the winter of 1952, The Galveston County Daily News reported 19 University of Texas Medical Branch physicians, nurses or family members contracted polio within a month.

The anxious atmosphere in Texas hospitals paralleled the panic and uncertainty of the world outside. Physicians and nurses operated under the terror of contracting polio or, worse, taking the disease home with them. As patients struggled through polio’s acute state, physicians often distanced themselves from their charges, standing in doorways or making observations through a glass partition. This fear was not unfounded. During the winter of 1952, The Galveston County Daily News reported 19 University of Texas Medical Branch physicians, nurses or family members contracted polio within a month.

The epidemics refused to abate. With each passing year, polio increased throughout the country. The numbers surged from 9,000 cases in 1941 to 27,000 in 1946 to more than 42,000 in 1949. By 1952, 58,000 cases were reported nationwide—4,000 in Texas alone. Each year the medical community and the public battled the disease. Each year frightened parents prayed for a cure.

Research provided the salvation. The arbitrariness of the polio virus ensured that nothing short of a vaccine would wipe it out. For many decades, efforts to develop a safe and reliable vaccine fell short. The tide began to turn during the early postwar years as one groundbreaking discovery and field trial after another unlocked the mysteries surrounding polio. The result was the development of the Salk and Sabin vaccines.

Public support was a primary catalyst for the Salk and Sabin discoveries. By 1945, many destructive diseases, including yellow fever, smallpox and cholera, had virtually disappeared from the American scene. New medications, technology and improved hygiene significantly curtailed other threats, such as tuberculosis, venereal disease and childbed fever. These medical triumphs, compounded by the atomic finale of World War II, instilled Americans with a profound faith in the power of science.

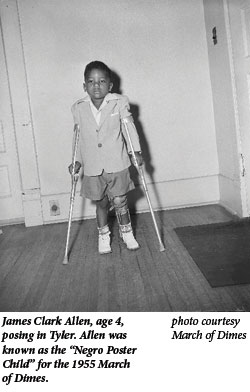

Embracing the link between eradicating polio and personal responsibility, Americans got involved. Hollywood celebrities solicited for the March of Dimes. Hats were passed. Mothers marched each January, and schoolchildren collected dimes. By 1954, Texas chapters of the March of Dimes had raised $67 million since the initiative began 15 years earlier. Other state chapters followed suit. The fear of polio and enthusiasm for scientific discovery reached beyond fundraising. Haunted by past epidemics and the prospect of future ones, parents wanted to leave little to chance. They volunteered their children for massive polio field experiments, including the gamma globulin trials of 1952 and “Operation Polio” two years later. They were the biggest scientific experiments ever conducted, and their success ensured that one of the most feared diseases of modern times became a memory for most people.

Yet polio is with us still. The vaccines failed to abolish the disease. Though polio has long been eradicated from the Western Hemisphere, certain developing countries continue to confront the disease. Fresh outbreaks have been reported recently in Nigeria, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India, where political and cultural resistance to vaccinations has left young populations in jeopardy. The World Health Organization, supported by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, Rotary International and the United Nations Children’s Fund, has launched an initiative to eradicate polio worldwide by 2013. To meet the deadline, polio-free countries must remain properly funded and committed to vaccination.

While Texas parents are choosing whether to vaccinate their children, there is a more important consideration embedded in this question of “conscience.” The anti-vaccine movement grows exponentially while our cultural memory of the fear and devastation surrounding childhood diseases like polio ebbs. The world is shrinking, and polio is just one of many maladies that could recur because of well-intentioned decisions to decline vaccination. Parents do deserve a choice about their children’s health and safety. The parents of the polio years chose to line their children up for Salk and Sabin vaccines. They helped eradicate a dreadful childhood disease. Let that be a lesson we never forget.

Heather Green Wooten, an independent historian, is the author of The Polio Years in Texas: Battling a Terrifying Unknown (Texas A & M University Press).