How To Turn Texas Blue

Mary Beth Rogers' new book is a blueprint for turning Texas blue, or at least giving Democrats a fighting chance.

A version of this story ran in the January 2016 issue.

Mary Beth Rogers ran the last successful Democratic campaign for the Texas governor’s office. The year was 1990 and the candidate was Ann Richards. Four years later, Rogers ran Richards’ re-election campaign — a loss that gave us George W. Bush. As Rogers writes in her new book, Turning Texas Blue, she has “seen both sides of Texas politics — euphoric victory and bitter loss.” And like other Texas Democrats, Rogers has spent the last 25 years suffering through one of the most miserable runs of a major political party in memory. She’s watched as Democrats have slipped further and further into irrelevance, even as the GOP lost interest in governing and began catering to its increasingly extreme far-right wing.

It’s easy to lash out at conservatives or wallow in despair among the like-minded. But Rogers has done something constructive instead: She’s spent years thinking about how to restore some kind of balance to Texas politics. Her book is a blueprint for turning Texas blue, or at least giving Democrats a fighting chance. In the last chapter, excerpted here, Rogers offers a 10-point plan (we have space for only six) on what to do. And Lord knows there’s a lot. — Forrest Wilder

If I were still a Texas political operative — a player in the game with sophisticated analytics, unlimited resources and a Democratic candidate for governor savvy enough to understand we needed a new game plan — I’d write one of those long memos that I used to prepare for Ann Richards.

I’m not that kind of player anymore, couldn’t be even if I wanted to. I was never much of a tactician, anyway, only a writer who synthesized the facts and ideas floating around and put them into some sort of organized plan for action. In a weird sort of way, I also actually enjoyed managing people and carrying out a plan that could bring order from chaos. That was “my thing.”

The focus of the memo I want to write is the race for governor. That is where the process of turning Texas blue has to begin, at the top. Of course, the U.S. Senate is always a possibility for the right Democrat at the right time, particularly if Senator Ted Cruz self-destructs between now and 2018. Democrats also need to peel away the Republican layers of control over the legislature, an important facet of turning Texas blue. But the governor’s office is the big prize. It is the key to returning Texas to political sanity.

I don’t have the candidate now or the resources to jump-start a campaign this year or next, but I’m going to write that memo anyway. Presumptuous? Yes. Opinionated? You bet! Out on a shaky limb? Obviously. Most of us who love politics always throw ourselves into shaky ventures. That’s what makes it exciting. An intense political campaign can narrow our focus and shut out normal life. It can be an addictive experience: a rush so thrilling when we win, but so deadly exhausting when we lose.

Many years ago, I decided to remove the political blinders that blocked out the rest of the world. I wanted a clearer, less biased view of life. It is not that I didn’t care about what happened to the causes that had engaged me for so many years. I just wanted a different way to approach them. I’m hoping that years of experience outside of the political arena in my more normal world of family and work will provide a new perspective to promote the causes I still care about.

I do admit to a kind of crazy hope. I just hope that I’m a little more wily now, with a tendency to be more realistic than before. So here are a few ideas about how to loosen the GOP’s grip on America’s reddest state.

DEAR TEXAS DEMOCRATS…

First, let’s get the numbers out of the way. Let’s use the analytics as a backdrop for all that we do, but not as the only factor to consider.

If we don’t get the numbers right, we don’t have a chance to win on any other front.

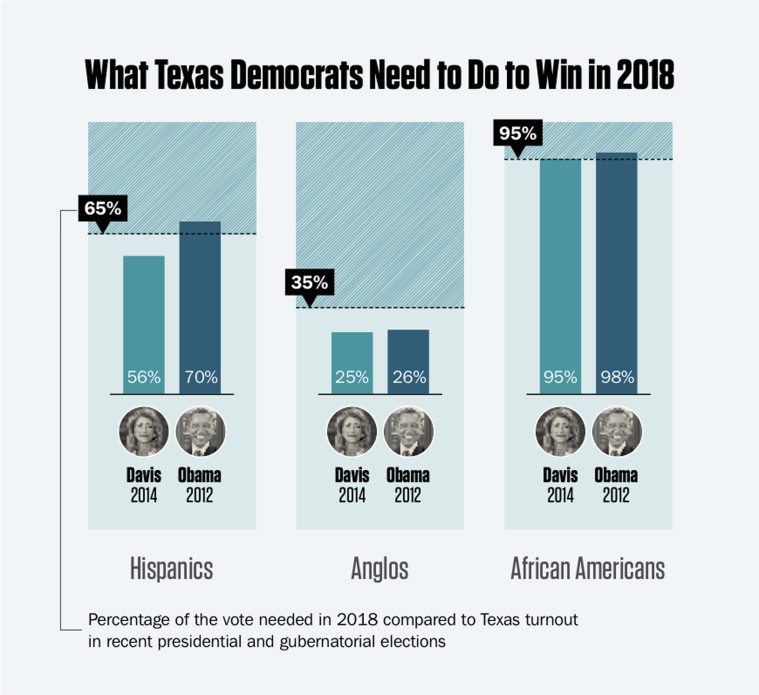

This is what we know: We have to begin winning at least 35 percent of the white vote statewide to be competitive. That’s a big jump from the 25 percent that Wendy Davis got in 2014. I believe it is doable. If we are lucky — and luck will obviously play a part in all that we do — the 2016 presidential election might help us along. If we presume that Hillary Clinton, or some other relatively appealing Democratic presidential nominee, campaigns on issues that matter to centrist voters, it might be possible to draw up to 30 percent of the white vote in Texas. If that were to happen, then the margin for Republicans over Democrats could dip into the single digits, say, a seven or eight-point advantage. These numbers would not be impossible to overcome in future elections.

Although Barack Obama lost Texas in 2008 and 2012, he carried the African American vote by 98 percent. He got a paltry 26 percent of the white vote. If he had managed to win more than 30 percent of the white vote, as he did in Virginia, Florida, and North Carolina, and if he had invested heavily in a GOTV effort as he did in those states, he might have won Texas too. Hard to believe, isn’t it? If the 2016 Democratic presidential candidate attracts more white Texas voters than Obama did, Democrats would have a larger pool to begin wooing for the 2018 statewide campaigns. There are a lot of “ifs” here, I admit. We just have to keep reminding ourselves that white voters make up about two-thirds of the total electorate in off-year elections, and no Democrat since Ann Richards in the 1990s has succeeded in reaching them.

We Democrats still have to increase our vote totals among our base. That means reaching the 65 percent threshold with Hispanic voters, keeping 95 percent of African American voters, and winning Asian, millennial, and new urban voters who are more in tune with the values and issues of the Democratic Party than with the crazy extremists who hold power in Texas today. So if we can pump up the raw numbers among our solid base of Democratic voters (who can be easily identified after the 2016 presidential election), these are the percentages we need to reach in 2018:

- Hispanics — 65 percent

- African Americans — 95 percent

- Anglos — 35 percent

This is not big news to anyone who studies Texas politics. The larger issue is how to do it. That’s always the rub — not what, but how. Here are ten ways to begin.

1. FIND THE RIGHT LEADER

We’ve come a long distance from the old Texas Way, but Texans still gravitate to leaders with big personalities who have a strong sense of self that is reflected in their pride, independence, and directness. It probably helps to have a little swagger too.

Don’t take this the wrong way. I’m an old-style feminist who believes that swagger is not gender-specific, but simply reflects self-confidence and willingness to take big risks. What we need is a man or woman who has enough self-awareness to understand what is involved in real leadership — building relationships with followers based on trust, vision, honesty, and competence. It has to be natural.

Remember the brashness of old Bill Clements and the Texas twang of truth-telling Ann Richards? Both had swagger. Both had big personalities. Both could inspire followers to move along with them, and neither was too concerned with the political correctness of their day. You knew they were willing to get in your face if they thought you were wrong about policy or politics. Each in very different ways was able to move outside of their party constituencies to create diverse coalitions of voters. Richards courted Republican women. Clements went after Reagan Democrats. They couldn’t be boxed into traditional party expectations, and because they were big personalities, they had magnetic qualities that attracted outsiders.

Texans still gravitate to leaders with big personalities who have a strong sense of self that is reflected in their pride, independence and directness. It probably helps to have a little swagger too.

I’m obviously looking for a Super Democrat. And my Super Democrat will have to rise above the damaged brand of our party, which has been fundamentally discredited after 25 years of harsh, largely unanswered attacks. The brand is sour. It has to be sweetened, and that may require our candidate to have one of those pivotal “Sister Souljah moments” to face down some absurdity within the Democratic Party that would drive away swing voters. When Bill Clinton denounced the black racism that ran through the lyrics of a rap singer named Sister Souljah, he proved to centrist voters that he was not a captive of the political correctness of an increasingly sensitive Democratic Party. He was independent. Texas’s Super Democrat has to have the same kind of independence to rise above party labels.

Our ideal leader will not be — cannot be — a new incarnation of Ann Richards, who was a product of her time and set of unique circumstances. The Super Democrat will have to create his or her own set of unique circumstances and make them relevant to a broad swath of Texas’s diverse population.

Party leaders are going to have to do a lot of soul searching to settle on a Super Democrat, and that involves asking some decidedly uncomfortable — and politically incorrect — questions. Is state representative Richard Raymond correct when he worries that it might be in the 2020s before his party can be viable enough to elect a Hispanic governor? Do Democrats need an Anglo bridge candidate in the 2018 off-year election who can appeal to enough white voters to break their knee-jerk Republican voting patterns? And if so, who is on the scene that might fill that role? At the same time, Democratic leaders should be recruiting and funding strong Hispanic candidates for key statewide offices that could give promising men and women opportunities for leadership now and in the future. Democrats have to wrestle with these issues in an honest, straightforward discussion. That’s the only way for the best answer and the right leaders to emerge.

2. FIND THE PATH TO REACH WHITE VOTERS

In 2014, Texas Democrats were able to pull only 25 percent of the white vote. But this was not only a Texas problem. In almost every contested election across the country in which a Democratic candidate for governor or U.S. senator lost, white voters were missing.

Former governor of Tennessee Phil Bredesen hit the nail on the head when he told party leaders, “If you have a product that’s not working, you don’t say, ‘our customers are lazy’ or ‘our customers don’t know what’s best for them.’” But that’s what Democrats have been saying in Texas for years . . . we’d win if only our voters would just vote! Enough of that. If we were in the business world and had been losing market share because of ineffective advertising for the same old unpopular product, we’d be saying that we need a better product and a different communications strategy. A better “product” for Texas would be a stronger candidate, an all-encompassing strategy, a more relevant message, and a more effective structure to reach white voters.

Václav Havel, the renowned writer and Czech dissident who became president of the new Czech Republic after the fall of the Soviet Union, used to talk about a “rule of everydayness.” The old Soviet system had little understanding or concern about how ordinary people lived each day, and it was one of the failures of a system that was more concerned with ideology — in a way, a more authoritarian form of political correctness — than with how people actually lived.

We need to start asking ourselves: What is the rule of everydayness for white Texans who are not in the top 10 percent of the wealthiest people in our state? What are the concerns about their families or their homes or their safety? What kinds of bills pile up every month? How are they going to manage the cost of higher education for their children? While Democrats, to their credit, have made an effort to understand the rule of everydayness for those left out of life’s bounties, they often write off the concerns of those who don’t necessarily live on the edges of life, but are stuck somewhere in the muddled middle, where problems still exist and struggles still matter.

Middle-class suburban moms worry about their teenagers experimenting with drugs as much as moms in poor inner-city neighborhoods do.

Middle-class families worry about putting their aged and infirm parents into inferior nursing homes as much as poor families do.

Single moms in suburban neighborhoods worry about child care, wage stagnation, and escalating rents, as do single moms everywhere.

Middle-class suburban families fret about traffic congestion, poor air quality, boarded-up shopping centers, and a whole lot of other issues that could be addressed by state officials — if they weren’t so busy trying to please Tea Party fanatics rather than ordinary folks, even those who live in suburbs.

Our ideal leader will not be — cannot be — a new incarnation of Ann Richards, who was a product of her time and a set of unique circumstances.

Suburban white voters are not on the radar of the Democratic Party of Texas. The message comes across loud and clear at election time.

“It passes my understanding how, particularly in the past few years, we’ve ignored the economic pain that’s been created in this country,” said Bredesen when he admonished Democrats to focus on economic issues that constrain middle-income suburbanites, as well as the working poor.

Democratic candidates from top to bottom could be shouting out issues that matter to white voters, using mail, social media, canvassing, and community meetings to reach new voters. They could bring up key questions that suburban voters want answered, such as:

Who is responsible when Texas law allows insurance companies to deny your claims for roof damage after one of our violent spring storms?

Who is responsible when our state allows a driller to put a rig for hydraulic fracking a hundred yards from your front door?

Who is responsible when the local nursing home closes in your small town because the legislature cut support for state medical facilities, and you have to move your 90-year-old mother to a facility 50 miles away?

We know that Republicans in the Texas legislature and the governor’s office are responsible for these and other issues that concern many Anglo voters. But do the voters know? Little insurrections bubble up all the time in the suburbs, and many could be used to woo white voters.

To reach the 35 percent threshold of white voters, Democrats can no longer ignore the issues that matter to them.

3. DISTINGUISH BETWEEN VISION AND MESSAGE

The great dancer and choreographer Twyla Tharp always creates a central theme, a big idea that is the organizing principle for her works. She has called the idea her “spine.” Everything in the dance flows from the spine, the structure that holds it all together. It is revealed subtly in the lighting, the music, the visual backdrop, the rhythm and timing of movement and interplay of the dancers. I think Democrats would benefit from considering how we choreograph a campaign that flows from its spine, its big idea, and its vision.

Wouldn’t it be a good idea for a Democratic candidate for governor to go into Denton and blame Greg Abbott and the Republican-controlled legislature for overturning the will of the voters on an issue that really mattered to them?

We need to go a bit deeper as a party and as individuals who want to lead it. We have to distinguish between the game of winning and the substance of vision and policy. What do we want Texas to be like by 2025? How can we fund public schools at a level to keep classes small enough for kids to learn and teachers to teach? How do we intend to keep the Texas economy strong and have good-paying jobs available to allow people to move into the middle class? What kinds of technological innovations would make our roads safer and our air cleaner? How could we really begin to create an “infrastructure of opportunity,” instead of just talking about it? We don’t need any more planks in a Democratic Party platform that satisfies all of our constituent groups. We just need some serious thinking about the future of Texas and its people.

More than 40 years ago, Royal Dutch Shell started a strategic vision development initiative led in later years by Texan Joe Jaworski, son of famed Watergate prosecutor Leon Jaworski. The process involved the amalgamation of facts and credible data projections about economic, political, environmental, social, and cultural changes that were already under way and expected to continue. Then Shell developed several scenarios projecting best- and worst-case events, written in a narrative, almost storylike form, that clearly laid out for non-experts what the future might hold if they took various kinds of actions or simply did nothing at all. From these scenarios, Shell officials gleaned enough information to come up with their big idea and choose the best path to achieve their goals. Variations on Shell’s scenario process have since been used by numerous international organizations, the U.S. military, and major businesses throughout the world. Maybe Texas Democrats would benefit from such a process.

As far back as 2002, former Texas state demographer Steve Murdock, whom George W. Bush later named as head of the U.S. Census Bureau, compiled an analysis of population projections through 2040 to indicate what might happen in Texas if the state did not start paying attention to its schools, its infrastructure, its in-migration patterns, and the downward trending economic indicators for its growing minority populations. Based on trends in the early 2000s, he noted that if serious changes were not under way by 2020, Texas could face a bleak future by 2040. Texas would not only be more ethnically diverse than the rest of the nation, it would also be older, poorer, less educated, and less healthy. But without a significant investment in people and schools, Texans both old and young would need increased public and private assistance, requiring massive expenditures. Murdock suggested that the year 2020 might be the tipping point for Texas: either change direction or face a more dismal future for the majority of its population. Not much has happened since 2002 to alter his projections.

A smart, independent-minded Democratic candidate could use information from this kind of data to create a vision to inspire change.

People have a way of imagining their own lives — how and who they want to be, and what they want for their families and their communities. The right candidate who takes on the responsibility to lead must articulate the kind of vision in which people can imagine a brighter future for Texas that is in sync with their own dreams.

Ann Richards and her team had a vision for a New Texas. Sure, it sounded corny at times, and its implementation was full of flaws. But it conveyed a set of values and an imaginative vision of the future where the doors of opportunity would be open to all Texans. This vision was specific enough in a hard-fought campaign to allow people to see how it could happen. It fit the times, the circumstances, and the aspirations of millions of Texans, and its simple two-word phrase revealed Richards’s beliefs and intentions for change. The right Texas leader will bring forward a vision that is authentic for the Texas of today.

4. DEVELOP A STRATEGY TO WIN

Think strategy, not tactics. This is my mantra. We cannot mistake tactical calculations for strategic thinking, as we have tended to do since Ann Richards lost in 1994. Yes, we will establish key goals — the percentage of white votes we need to win, the number of Hispanic votes we must hold, the desire to maintain African American loyalty, the development of the youth vote, the incorporation of gay, lesbian, and transgender Texans into our cause. None of that is new to our Democratic friends.

What we have to do differently is figure out how to reach those goals in very specific ways. That’s where strategy begins. It is a whole system approach based on accurate analytics that determine specific tactics that go into a plan, a budget, and a timetable based on facts, not hopes. Properly understood, a campaign budget should be a strategic document that funds priorities, measures results, and ensures that adequate funds are available when needed. Sounds easy. Simple common sense, no doubt.

Yet why did the Wendy Davis campaign run out of money two months before Election Day? While the campaign had goals, it did not have a strategy that meshed with a comprehensive budget that could ration scarce resources within a timetable to carry out a plan. No money for broadcast or cable media in the final week? No money for direct mail or canvassing of swing voters? No money for paid canvassers to supplement volunteers? Pity! The campaign did have a set of get-out-the-vote tactics, but they were based on erroneous assumptions, flawed data, and unrealistic expectations. A bold tactical effort can never rescue an inadequate plan. Didn’t work then, won’t work now.

The most important time in a political campaign can be before it ever begins. That is when the candidate and consultants can be most creative, most logical, and most data-driven to organize a winning effort. That is when ideas are tested, when resources are identified, and timetables can be organized. That is when all of the aspects of the campaign can be shaped into a coherent whole that can serve as the road map when the action becomes fast and furious. Any campaign that shaves time at the outset will be in serious trouble at the end.

7. RUN A WHOLE-STATE CAMPAIGN

Texas has 254 counties. In recent elections Democrats have focused on only six big ones, plus the Rio Grande Valley. There are at least 50 additional counties in Texas that have blocs of minority voters, as well as white voters who might be lured back to voting Democratic. So go where no Democrat has gone since Ann Richards ran for governor. Go everywhere!

Republican Bill Clements ran a 254-county campaign and ventured into strange new territory for a Republican. George W. Bush left safe Republican areas to make a major push deep into East Texas, which had been Democratic territory in 1990.

Democrats have not ventured into new areas in almost 20 years. It will be difficult to shake the conventional wisdom in our party that all we have to do is to work harder to get out the base vote in the big cities and the Valley. But Democrats have the potential to expand their base vote in at least 29 mid-size cities throughout Texas, as well as to pick up disaffected moderate Republicans in key suburbs.

Dr. James Henson, who runs the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas at Austin and conducts regular polls for the online Texas Tribune, estimates that 20 to 30 percent of Texas’s moderate Republicans might be open to voting for the right Democrat under the right conditions in the right kind of election. They just have to be identified and bombarded with relevant issues and effective tactics. To do so on a whole-state level will take resources: money and people. It will also take a candidate who can lead the party — against years of resistance — and understand that this is the first step toward rebuilding the Democratic Party as a viable institution in Texas.

8. CONNECT THE DOTS BETWEEN POLICIES AND POLITICS

In 2014, Denton, just north of Dallas, became the first city in Texas to ban the practice of fracking within its city limits. Fracking, or hydraulic fracturing, is the process of injecting water, sand, and chemicals underground to extract oil and gas from shale formations. Denton, with a population of about 125,000, has been the epicenter of the practice because it sits atop the gas-rich Barnett shale formation that stretches across 24 North Texas counties. Natural gas extracted from shale formations is a cleaner fuel source than coal. But the process of extracting it has, so far, created other problems. In Denton, after major oil companies put their rigs near residential areas and local schools, residents began to complain about poor air and water quality, as well as disruptive noise from drilling, heavy truck traffic in residential neighborhoods, and even an increase in low-magnitude earthquakes.

A local citizens group gathered sufficient signatures to get a proposed ordinance banning fracking within city limits on the November ballot. They won the election by a margin of 59 percent to 41 percent, despite the almost $700,000 that oil companies had spent to defeat it. Yet the day after the election, Texas Railroad Commissioner Christi Craddick, one of the three elected Republicans who run the agency that oversees oil and gas production, announced that the agency would not honor the town’s vote to ban fracking, and the practice would continue. Adding insult to injury for Denton residents, the Republican majority in the 2015 legislature passed a law that forced Denton to repeal its anti-fracking ordinance. The new law also prohibited other Texas cities from stopping fracking in their communities. Governor Greg Abbott signed the new law with great fanfare. But here’s the disconnect: Denton also voted overwhelmingly for Abbott and the Republican slate of candidates that took away their power to enact certain local ordinances. Wouldn’t it be a good idea for a Democratic candidate for governor to go into Denton and blame Greg Abbott and the Republican-controlled legislature for overturning the will of the voters on an issue that really mattered to them?

Credible Democratic candidates — local and statewide — can use issues like this to drive a wedge between local voters and their Republican representatives. It is one way to use voter microtargeting to begin shaving Republican vote totals in their base counties.

There are other issues — even local disasters — that result from lax regulatory policies or failure to respond to desperate community needs. In 2013 a fertilizer plant, where tons of ammonium nitrate were stored, exploded in the small community of West, just north of Waco. The blast from the explosion and resulting fire killed 15 people, injured 160 more, and damaged or destroyed 150 buildings, including the town’s middle school, a nursing home, and a 50-unit apartment complex. First-responder volunteer firefighters were among those killed because they entered the burning building without knowing that it contained volatile materials. Incredibly, the fertilizer company had never informed the local fire marshal about the explosive materials, and members of the community had no idea that the plant could be dangerous. Abbott, who was attorney general at the time, refused to order similar facilities to publicly disclose the explosive materials on their sites. Enterprising Texas news reporters dug up the facts anyway.

There are 92 of these fertilizer facilities all across the state, and many are located near homes and schools. Yet two years after the disaster, Texas had made no changes in law, policies, or regulatory measures to protect residents from similar explosions. During a recent inspection by the state fire marshal, only one-fifth of those plants had a sprinkler system to put out a small fire that could cause a major explosion. Fifty-two facilities had no means of fire protection except handheld fire extinguishers, and 22 had no fire protection features at all. Who is responsible?

A savvy candidate in a whole-state campaign could build a compelling case among rural and suburban voters that any Republican who allowed these life-threatening situations to continue should to be thrown out of office. Yes, it will take research, resources, and relevant messages from candidates willing to take this kind of plunge into local issues, but it can be done.

Someone once asked Texas music icon Willie Nelson how he had been able to write so many different kinds of songs. He said that there were millions of melodies floating through the air. You just had to pull them out. There are a lot of big stories that matter to people floating through the air in Texas. Democrats just have to pull them out and start using them to win voters they have long ignored.

Well…that’s it…the end of my memo. Now, it’s up to you. If you find it useful and are still interested, you could put this summary on your “to-do” list or in your smartphone.

- 1. Find the right leader.

- 2. Find the path to reach white voters.

- 3. Distinguish between vision and message.

- 4. Develop a winning strategy based on facts.

- 5. Assume the role of a Republican strategist.

- 6. Drop the hype.

- 7. Run a whole-state campaign.

- 8. Connect the dots between politics and policy.

- 9. Spread the word about Republican extremism.

- 10. Keep Texas money in Texas.

This list won’t change Texas. That’s going to take people with vision, fortitude, and perseverance. Now that I’ve gotten my two cents in, I’ll cheer them on. Texas is ready for them. Texas is ready for change.

Correction: The story originally stated that Mary Beth Rogers ran the last successful Democratic campaign for statewide office. In fact, she ran the last successful campaign for the Texas governor’s office. The Observer regrets the error.

[Featured illustration: Chris Madden]