The Top Redistricting Fight Moments

Members came out of the woodwork Wednesday to fight for their parties—and pieces of turf.

For most of the legislative session, you can forget that there are 150 members in the state House. After all, most of them stay quiet. Most don’t take visible roles in debate or negotiations. Freshmen in particular are still learning the game and policies. But make the debate entirely about politics, threaten their turf or their friends, and the most forgettable of lawmaker comes out swinging.

The House spent almost 16 hours Wednesday, going tooth and nail on redistricting. The process, drawing new districts at least once every ten years that reflect the latest Census data, is almost entirely about partisan power and incumbent advantage. The goal is to make as many seats “safe” for the ruling party as possible, to ensure dominance over the decade. The map that passed last night gives Republicans a strong advantage overall and protects most incumbents—although with a supermajority the GOP couldn’t protect everyone. 12 Republicans remain “paired” together in single districts, meaning one will have to either move or there will be a primary. Democrats aren’t happy that the map takes one representative away from Harris County, traditionally a Democratic stronghold, and leaves two of their members paired as well.

Every other debate in the House is ostensibly about what’s best for the state’s residents—school kids, business owners. We watch as a few active members argue that their bill makes the state better somehow. Redistricting, meanwhile, is all about power and politics. Nasty and personal, it seemed more members got involved in the fight over politics than in any major piece of policy so far this session.

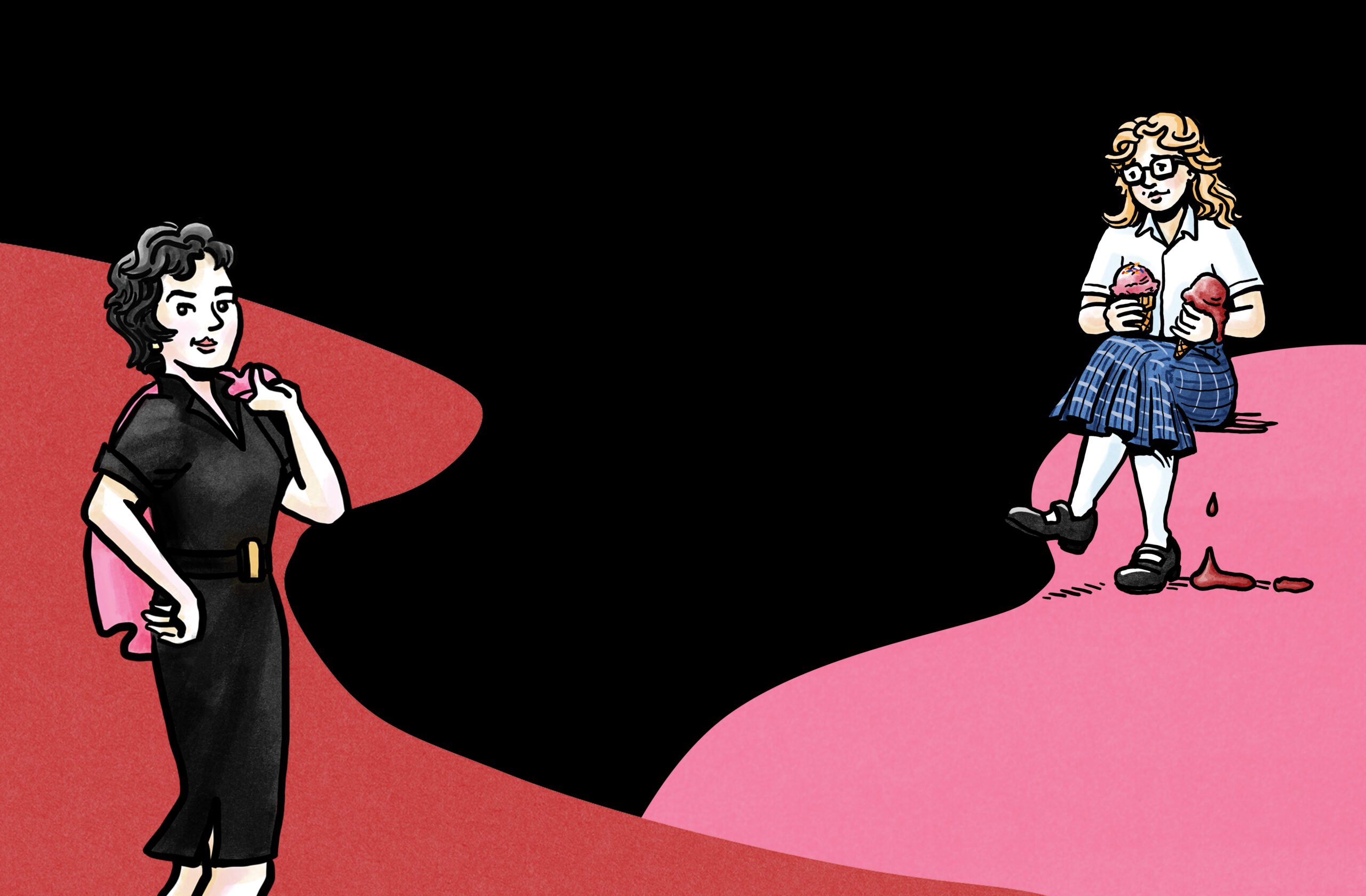

So here are some of the most exciting and bizarre fights of the evening—featuring some members you might not see again for the decade.

Tracy King vs. Jose Aliseda

Rep. Tracy King, D-Batesville, wanted to keep more of the district he currently represents, so he proposed moving freshman Republican Jose Aliseda’s district over a bit, which would include slightly more registered voters with Hispanic last-names—and slightly fewer Republican voters. It was a “negligible” change according to Republican Redistricting Committee Chair Burt Solomons, and Aliseda expected it would impact around 600 votes. But it was a close race last time, and Aliseda decided to mount a partisan attack.

“You understand I’m a freshmen?” he said to King.

“It’s painfully obvious,” King shot back.

“Any reduction in my Republican numbers coud affect a possibility about [reelection],” Aliseda said, unaware, apparently, that members normally do not make their partisan bids quite so blatant.

Rep. Mike Villarreal, D-San Antonio, argued that Aliseda was actually opposed to the change because it would include more Hispanic voters in his district. (The move would have decreased the total number of Hispanic residents, but because many of those residents are non-citizens and can’t vote.) “You’re fighting this amendment because it actually increases the number of Hispanics that can vote in your election,” Villarreal argued.

“I’m opposed to the fact that it changes my district to a more Democratic district,” Aliseda eventually explained.

When his pleas for protection fell on deaf Democratic ears, Aliseda then took it a step further. “I would ask that the other Republican members in the House and the other freshmen join me in voting against this amendment,” he said. The amendment failed, not surprisingly, though Aliseda wanted to make sure there were no hard feelings. “Mr. King and I have been getting along until now,” he said, adding that King was “a brother from another mother.”

When King called him out for making things so partisan, Aliseda shrugged it off. Redistricting, he said, is “a political process, one of the most political thing we do.”

No need to convince us.

Valley Democrats vs. Aaron Peña

Aaron Peña isn’t popular with Democrats these days. After all, he was elected as a Democrat and then switched parties, helping give the Republicans a super-majority. So they were especially upset when his new district, shaped a bit like a Transformer figurine, cut out most of McAllen Democrat Veronica Gonzales’ district—the new maps give her only has 1.5 percent of the same territory she currently represents. She will likely still win since the region is heavily Democratic, but Valley Democrats weren’t happy. While the map was supposed to have been drawn with input from each region, no one in the Valley delegation said they had offered such a plan. Unspoken was the belief that Peña was somehow responsible for the new set of districts, since it drew his district to maximize conservative votes.

Gonzales offered an amendment that would have restored the districts to their current borders. Even that was settling in some ways—many Ds think there should be a new Hispanic-majority district in the region. But Peña took the mike to argue against the amendment.

“I think Rep Gonzales is a fine member,” Peña said. “She’s a liberal member but that’s fine. I’m a conservative member but that’s fine.” A hushed boo went through the chamber. Peña argued that the plan was fair and that “things have gotten a little too personal here.”

But they were just getting started. Democratic Rep. Joe Farias took the stage, telling everyone he wanted to get past the “ranting and raving about Republicans and Democrats.”

“Under what party did Peña run this past election?” he asked Gonzales.

“He ran as a Democrat,” she replied.

“He bamboozled all the folks who voted for him!” Farias exclaimed. Boos and hoots echoed off the walls. Gonzales, wisely, refused to respond, except to say, “There’s been some hanky panky going on.”

The amendment failed.

Black Caucus vs. Burt Solomons

While the biggest fight on redistricting will likely be in court, Democrats eagerly laid the groundwork for cases against the proposed maps. Every exchange was recorded into the official House Journal, so that it could be used in court. When Democratic Rep. Mark Veasey found out the inclusions would be automatic, he couldn’t contain himself. “Sweet!” he exclaimed with a grin at the podium. “Thank you!”

The Democrats will try to show that “communities of interest” were split, and particularly that the map does not maximize the representation of minority groups like African-Americans and Latinos. Early on, Democrats began arguing the map was “retrogressive”—meaning it unfairly denies representation to minority groups. Rep. Harold Dutton, D-Houston, argued Solomons had not fairly counted incarcerated populations, who he said should count as part of the population in the last place of residence.

In Dallas County, black Democrats argued that the map swapped out a black district for a Hispanic one. Black Caucus chair Sylvestor Turner spoke as ten or so of the caucus members stood behind him for support. “We are not here to participate in our own demise,” he said. “We are not interested in being an ineffective group.”

He told Solomons the map was “outright retrogression,” explicitly saying the Black Caucus did not approve—and was not sufficiently included in the discussion. It’s the kind of statement that can bolster legal arguments against the map.

Solomons pointed out that his office was close by Turner’s. “I could have come down to your office and you could have come down to my office,” Solmons said.

“You’re doing what a good lawyer does,” he added. “You’re creating reasonable doubt.”

We’ll have to wait to see if the courts agree.