Cracked

Despite a U.S. Supreme Court ban, Texas has continued to send mentally retarded criminals to death row. Will a Mexican immigrant's case correct this injustice?

UPDATE: On Friday, April 15, the Texas State Board of Examiners of Psychologists issued a reprimand against Dr. George Denkowski, a criminal psychologist whose questionable methods were exposed in this story, originally published by the Observer in January of 2010. Denkowski was the go-to psychologist for prosecutors who wanted to prove that defendants were not mentally handicapped—and therefore eligible for the death penalty. As reporter Renée Feltz uncovered, Denkowski had his own evaluation methods that contradicted mainstream approaches, and his opinion helped put 14 current inmates on death row—people determined to be mentally handicapped by other psychologists. Feltz’s story was recently named a finalist for a 2010 Investigative Reporters and Editors Award. Because of the state board reprimand, Denkowski will no longer be able to evaluate criminal defendants, and the decision may allow some of the inmates he evaluated an opportunity to challenge their death sentences.

Watch Renée Feltz on Democracy Now!

Floresbinda Plata hadn’t seen a doctor during her entire pregnancy in the desolate village of Angoa in Michoacan, Mexico. But after four hours of painful labor, she sought help at the nearest clinic, an hour away by dirt road. After Plata arrived, Dr. Luis Zapien recalls, “We pulled [the baby] out and he was born completely flaccid and purple.”

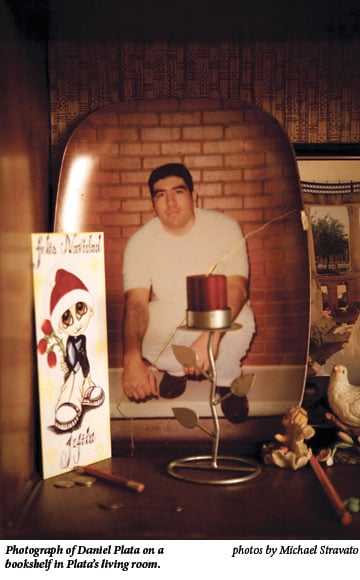

Floresbinda heard the doctor say that her son was dead before he untwined the umbilical cord that was wrapped twice around the baby’s neck and began mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. After several minutes, though, her son began breathing. But the lack of oxygen had already damaged his brain. A nurse checked off a simple behavioral checklist—did he cry, did he respond appropriately?—and gave him two points out of 10, a score for a newborn with profound cognitive defects. Just an hour into his life, and 20 years before he would be sentenced to die in Texas, Daniel Plata was already being tested for mental retardation.

By the time he was 3, Daniel could say “Mama” and “Papa,” but not much else. His grandmother grew frustrated when, as he got a little older, he couldn’t seem to run simple errands. “If I sent him for lard he would lose the money,” says Cynthia Hernandez. “If I sent him for peppers he would bring back tomatoes.” In school, Daniel stood out as a slow learner. His first-grade teacher, Eleazar Herrera Solis, “tried to get him to be the same as the rest,” but “the child could barely read.” His violent father complicated matters. Several times a week he would come home drunk and attack Floresbinda. As the oldest child, Daniel would try to protect his mother and two brothers from Isidro’s fists, belt and occasionally his machete. In the process he became the target of his father’s rage.

In 1986, Floresbinda fled with her sons to the United States, hoping for safety and a better life. She found work as a janitor in Houston. When the boys registered for school, Daniel—then 10—was put in first grade. His friend Nasario Vasquez remembers him as “the kid who got picked last” for basketball. “For Daniel the games had no rules,” Vasquez says. “He would just run down the court and throw up a crazy shot with no coordination.”

When Daniel was 15, he was socially promoted to the ninth grade. He acted up in class and was sent to an alternative learning center. He was flagged as “extremely low” performing by his teacher, Terry Rizzo, in a note to the school counselor. At first Rizzo assumed Daniel was having trouble understanding English, but after studying his behavior, she thought he might be learning disabled. She urged the school to test Daniel to see if he should be placed in special classes. But he was never tested and before his ninth-grade year was halfway over, he dropped out.

Daniel started working as a busboy at Luby’s to help support the family. He took to carrying his mother’s gun around as a way to look tough. Then one night in March 1995, Daniel brought the gun along when he and some friends went to rob a nearby Stop’n Go.

He had drunk about 20 beers and smoked PCP-laced marijuana, he later testified, so his memory of the night is hazy. But the store’s security camera shows Daniel pointing his gun at the clerk, Murlidhar Mahbubani, and yelling, “Give me the money!” His two friends jumped over the counter and emptied the cash register of about $50. Then Daniel bent over the counter and shot Mahbubani several times in the back.

The store’s surveillance system clearly videotaped his face. It also showed him, on the way out, using his shirt to wipe his fingerprints off the door.

Within 30 hours, police had Daniel in custody. He confessed to Mahbubani’s murder soon afterward.

During his trial in 1996, prosecutors repeatedly played the videotape showing Daniel ruthlessly killing Mahbubani. The guilty verdict was a foregone conclusion. During the penalty phase of the trial, Daniel’s mother and stepfather testified that he was a good son, and his attorney argued that he was “passive, docile. For one minute and a half, he just lost it.” In the prosecutor’s closing statement, he urged a death sentence: “This was a shocking crime, and it deserves a shocking punishment.” The jury agreed. Daniel Plata was sentenced to die by lethal injection.

Within four years, Plata’s appeal had wound its way through the courts and ended in failure. His mother sought help from several lawyers in Mexico; her inability to speak English made it hard for her to find legal assistance in the United States. “I would sleep and wake up with the same thought about each day passing … that he was one day closer to death,” she says.

Two more years passed before officials from the Mexican Consulate in Houston called her and said a lawyer wanted to ask about Daniel’s history of being slow. The lawyer thought it might save his life.

In 2002, six years after Daniel Plata landed on Death Row, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a case called Atkins v. Virginia that “executions of mentally retarded criminals are cruel and unusual.” Even though mentally disabled people can understand the difference between right and wrong, the court reasoned that they are less able to control impulsive behavior or learn from mistakes. The court supported its decision by pointing to bans on executing the mentally retarded in 17 states and in federal cases as “evolving standards of decency.”

Like most of the states that had already passed bans, the justices used a clinical definition to establish the level of mental retardation that would exempt Daryl Atkins, the Virginia defendant, from death: below-average intellectual abilities defined by an IQ score of 70 or below and “deficits in adaptive behavior” such as practical and social skills. Both of these limitations, the court ruled, had to be present before the age of 18.

But the court left it up to the states to choose their own definitions of mental retardation. Since 2002, eight more states have passed laws that use the clinical definition cited in Atkins. Texas is not one of them. With bipartisan support, the Texas Legislature passed a law in 2001 mandating a life sentence for mentally retarded people convicted of capital crimes. But Gov. Rick Perry vetoed the measure, agreeing with critics that it was a “backdoor attempt to ban the death penalty.” Bans on executing the mentally retarded have been floated in every legislative session since but have never again come up for a vote.

In 2004, a Texas death row inmate named Jose Briseño contended that he was mentally retarded and shouldn’t be executed for murdering a Dimmit County sheriff. In the absence of legislative guidelines, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals wrote “temporary judicial guidelines” that have guided Texas courts ever since. In its Briseño decision, the court called clinical definitions of mental retardation, like those used by the U.S. Supreme Court, “exceedingly subjective.” Texas added its own set of additional criteria in the form of seven questions, including: “Did the commission of that offense require forethought, planning and complex execution of purpose?” If a defendant didn’t address these questions to the court’s satisfaction, he could be eligible for execution even if his test scores showed he was mentally disabled.

Most of Texas’ questions emphasize the events of a crime in deciding whether a defendant meets a legal definition of mental retardation. “I think much of that emphasis is inappropriate because it embodies the stereotype of mentally retarded people as unable to do anything,” says Sheri Lynn Johnson, a professor at Cornell Law School and co-director of its Death Penalty Project. In Texas, under the Briseño standard, if you’re capable of committing a murder, it’s difficult to establish that you’re also mentally retarded.

In other states, evidence of mental retardation is heard in pretrial hearings that decide whether a person is even eligible for a death sentence. In Texas, prosecutors have fought successfully to hold off evidence of mental retardation to the penalty phase of a trial, meaning that jurors consider it only after they have convicted a defendant of murder. Keith Hampton, legislative director of the Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association, says “the gamesmanship is this: I can make you hate this guy so much that you won’t care if he’s mentally retarded.”

Since 2002, Texas has removed just 13 men from Death Row after they were found to have the mental and emotional development of 12-year-olds. In contrast to a 40 percent success rate for Atkins appeals nationally, just 28 percent have been successful in Texas. “I suppose you could imagine that Texas Death Row inmates are smarter than everyone else,” says Johnson, “but I’d be surprised.”

During Daniel Plata’s original trial, prosecutors had portrayed him as a sophisticated criminal who’d tried to hide his identity and erase his fingerprints after murdering Murlidhar Mahbubani. But attorney Kathryn Kase figured that Plata’s accomplices, who made no such attempts, had realized the store’s security camera had captured their faces and didn’t bother. If anything, she thought the crime showed how Plata was prone to act impulsively, as mentally retarded people are known to do. And when she interviewed Floresbinda Plata, she learned that there was a family history of retardation: Daniel’s younger brother, Jesus, and his Aunt Celianel had both been diagnosed as mentally retarded. His cousin, Rosalba, had Down syndrome.

To prove that Daniel Plata should be exempt from the death penalty, Kase had to start by showing that he had an IQ of 70 or below. She hired Antonin Llorente, a neuropsychologist who had designed intelligence tests and was a native Spanish speaker—important because it would allow him to test Plata in the language he understood best.

In May 2003, Llorente spent about five hours with Plata in a small visiting room at the Polunsky Unit in Livingston, where men on Death Row are housed. He began by asking Plata if he felt he was mentally retarded. Plata vehemently denied it. When Llorente asked him to draw his family, the 28-year-old man “drew stick figures,” which Llorente noted in his report were “appropriate for children, not mature adults.” Then he measured Plata’s intellectual ability through puzzles and math questions that are part of a test called the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale.

Llorente reported that Plata’s IQ score was 65. Even in Texas courts, it’s generally accepted that IQ scores include a “standard error of measurement” of five points up or down. This means a person’s IQ score falls within a range; a person who tests at 75 could still be considered retarded. Plata’s 65 was a strong indication that his intellectual abilities were below average and met the U.S. Supreme Court’s standard for mental retardation.

The next psychologist to evaluate Plata was Texas prosecutors’ favorite tester, George Denkowski of Fort Worth. Denkowski’s career stretched back 30 years to when he directed a 15-bed group home for mildly retarded adolescent offenders in Houston, teaching them adaptive skills that would improve their behavior. He’d also been the chief psychologist at the Fort Worth State School, a 365-bed facility for people with all ranges of mental retardation. Since 1989 he’d been in private practice conducting psychological evaluations. Denkowski had also directed a national study of mentally retarded people in state prisons.

After the Atkins decision in 2002, Denkowski became the first choice for Texas prosecutors. He would ultimately testify in 29 cases—nearly two-thirds of such appeals in Texas to date. In one of the first cases he worked on, Denkowski found James Clark, a man accused of raping and killing two teenagers in Denton, mentally retarded. The state dismissed him after that finding and hired another expert who disagreed. Denkowski’s opinion was presented by the defense to no avail, and Clark was executed.

In 29 cases, Denkowski has found defendants retarded only eight times. By 2006, when he tested Plata, Denkowski had garnered an “almost Dr. Death status” among defense lawyers, according to attorney Robert Morrow. Morrow represented Alfred DeWayne Brown during his 2004 trial for killing a clerk and a security guard at a Houston check-cashing store. Morrow said “Denkowski pretty much thought that if you had engaged in criminal behavior you were not retarded,” Morrow says. Brown remains on Death Row.

The work was lucrative. Denkowski charged prosecutors hourly rates of $180 for evaluations, and $250 for court testimony. Most of the cases he worked on were in Harris County, which until 2009 pursued more death-penalty sentences than any other county in Texas. Between 2003 and 2009, Harris County paid him $303,084 for his services, according to the Harris County Auditor.

Denkowski did not respond to repeated interview requests for this story.

EDITOR’S NOTE: In the print and earlier Web editions of this story, the Observer mistakenly reported that Judge Mark Kent Ellis was a federal judge. He is a state judge who presides over the 351st District Court.