Boom Town

Is a natural gas windfall making the earth quake in North Texas?

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is an updated version of the story that appeared in the Sept. 4 edition.

Throughout Cleburne’s 142-year history, people have known it as a small, quiet town where residents live happily away from the hubbub of neighboring Dallas-Fort Worth. That changed this summer when a series of minor earthquakes jolted the area. Though no serious injuries or damage were reported, the quakes upset nerves, stirred controversy and drew media attention from far corners of the country. They also gave the folks of Cleburne something in common not only with the urbanites of DFW, but those across the ocean in Basel, Switzerland.

“It shook my chair and rattled things on the wall,” City Council member Gayle White says of the first earthquake on June 2, a 2.8 magnitude tremor she says lasted only seconds.

As quakes continued in subsequent weeks, calls rolled into the city’s 9-1-1 emergency operators, and longtime residents tried to make sense of brief shaking sensations they had never before felt.

“I thought somebody had run into the house with a tractor,” says Sharla Harwell, 48, of Cleburne, recalling the booming sound accompanying one of the quakes.

What caused the booms? Nearly everyone has a theory, and the prevailing one around here seems to be that “the boom” caused the booms.

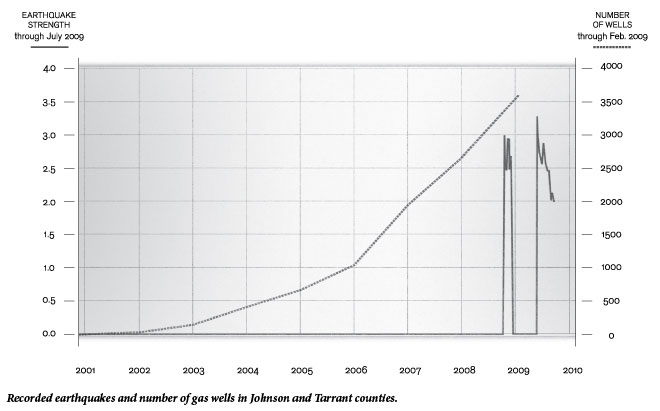

“The boom” has been in natural gas production. Over the past six years, Cleburne’s natural gas boom has produced numerous millionaires and filled city coffers with sizable royalties.

N.R. Powell, 74, who has lived in Cleburne his entire life, says in jest of the area’s proliferating wells, “All you do is walk 100 yards in any direction and you’ll find one.”

A town of about 30,000 in Johnson County, Cleburne is situated over the Barnett Shale gas field, where hydraulic fracturing is used in the extraction of natural gas. The process involves injecting gas wells with high-pressure water, along with chemicals and sand, to crack open the rock and release the gas.

Local concern over the possibility that natural gas activities may be causing the earthquakes “is directly related to the amount of mailbox money they receive,” says Chester Nolen, Cleburne’s city manager.

About half of Cleburne’s residents get mailbox money—monthly royalty checks from $300 to tens of thousands of dollars—for leasing their land for natural gas wells, Nolen says. In addition, landowners receive handsome signing fees, which once reached $16,000 though have decreased in recent years to between $2,000 and $6,000 per acre, he says.

Through the years, the city of Cleburne has received more than $25 million for allowing drilling on municipal land.

The Johnson County area isn’t the only one rolling in natural gas royalties. Adjacent Tarrant County, another of the 19 counties in the Barnett Shale, has likewise experienced a natural gas boom, and felt the first of several earthquakes on Oct. 31 last year. Since then, at least 20 more earthquakes, including several this spring and summer, have shaken areas in the two counties. The quakes are the first recorded in those counties’ histories.

A WORLDWIDE WEB

The recent earthquakes in North Texas should be viewed through a broader, global lens, as earthquakes elsewhere have likewise been tied to energy-industry activities.

For instance, in Basel, Switzerland, a geothermal project involving hydraulic fracturing was shut down in December 2006 after scientists concluded that the operation had triggered a series of earthquakes—more than 3,500 over the following year. That was reported by The New York Times in June in the wake of five earthquakes that rocked Cleburne earlier that month, and raised the question of whether natural-gas industry activities might be the cause.

According to the Times article, the Basel project involved injecting high-pressure water into holes drilled more than two miles deep to create a network of fractures. The goal in Basel was to circulate the water through the heated earth, after which it would emerge as steam.

The Basel and North Texas scenarios are not entirely analogous. For one thing, hydraulic fracturing in the Barnett Shale is designed to extract natural gas, not generate steam, and gas wells here are drilled at shallower depths averaging 1.4 miles, according to the Railroad Commission.

Still, some natural-gas industry activities in this area occur at greater depths than those of gas wells. And scientists are still learning the potential consequences of well activities at any depth.

In the meantime, communities around the world are enduring the trials and errors of energy-industry tycoons.

Project leaders in Basel, concerned about the sudden incidence of minor earthquakes in that city, decided one day to release well pressure in an attempt to halt the fracturing. As they did, a larger 3.4 quake occurred, accompanied by a loud noise that sounded to one project leader like a sonic boom. That man later told the Times, “It took me maybe half a minute to realize, hey, this is not a supersonic plane, this is my well.”

Natural gas industry officials in Texas have been less quick to assume responsibility for the North Texas quakes. However, Oklahoma City-based Chesapeake Energy Corp. recently acknowledged the possibility of fault relating to quakes in the DFW area. Chesapeake is the largest gas producer in Johnson County and the third-largest operator in the Barnett Shale, according to the most current information from the Texas Railroad Commission.

After staying relatively mum for months, Chesapeake sent an e-mail Aug. 13 to the Railroad Commission noting “a potential correlation” between Chesapeake’s saltwater disposal well at the southern end of the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport and earthquakes felt in that vicinity. The disposal well is used to dispose of saltwater waste from natural gas wells. A major fault runs through the airport, and the disposal well is about 2,400 feet away from it, according to the e-mail from Julie Wilson, Chesapeake’s vice president for public affairs.

“Although the research is not conclusive, Chesapeake has shut in that particular well as a precautionary measure,” her e-mail says.

Though Wilson’s e-mail to the Railroad Commission suggests no responsibility for the Cleburne earthquakes, it mentions a smaller regional fault in the southern part of Cleburne and says the company has shut in a saltwater disposal well in that area, too, as a precautionary measure.

Chesapeake officials declined to comment for this article.

THE DECIDERS

Chesapeake’s recent partial admission doesn’t appear to have been entirely self-initiated, but rather prompted by preliminary results from a seismic research project, which was organized by Southern Methodist University scientists and had been well publicized in the media. The beginning of Chesapeake’s Aug. 13 e-mail, in fact, refers to that research.

After multiple earthquakes hit Cleburne in June, city leaders there decided to hire a geologist to find out why. Then they learned that SMU scientists were conducting their own six-month study with 10 loaned seismic monitoring stations, funded mainly by the National Science Foundation. So Cleburne’s city council decided to save the expense and piggyback on SMU’s study.

Ironically, Cleburne’s deference to S.M.U. means that SMU—which has agreed to house the George W. Bush Presidential Library and think tank, and where Laura Bush is a trustee—will be prime arbiter of whether the natural gas industry is or isn’t the root of the earthquake problem.

Though there probably isn’t a major university in Texas that hasn’t benefited from oil and gas money, SMU’s ties to the energy industry are especially noteworthy.

* The hydraulic fracturing technique was pioneered by Halliburton Co. Former Vice President Dick Cheney was chief executive officer of the company from 1995 to 2000, and also served as an SMU trustee from 1996 to 2000. Some critics of SMU’s coziness with the company have referred to the school as “Southern Halliburton University.”

* The Bush-Cheney administration’s 2005 Energy Policy Act exempted hydraulic fracturing from regulation under the federal Safe Drinking Water Act. As a result, gas operators don’t have to divulge what chemicals they inject into the earth when they fracture a well. Concerned about the risks of groundwater contamination from fracturing, some members of Congress have been working on a bill to reverse that decision and require companies such as Halliburton to reveal the chemicals in their fracturing fluids.

* SMU renamed its geology department the Roy M. Huffington Department of Earth Sciences last year after receiving a $10 million endowment from Huffington, the late oil and gas man who in 1990 was appointed ambassador to Austria by former President George H.W. Bush. Huffington, an SMU alumnus, has given the university more than $31 million through the years, according to SMU Magazine. SMU has also received substantial gifts from other oil and gas industry figures.

* Last August, SMU was among three entities to share in an investment of more than $10 million by Google.org (Google’s philanthropy arm) in “enhanced geothermal systems,” a technology that relies on hydraulic fracturing. SMU’s portion was a nearly half-million-dollar grant for the earth sciences department to update its geothermal energy map of North America, which will help interested parties locate geothermal resources. AltaRock Energy Inc. and Potter Drilling Inc. received the rest of the Google investment. Google is a primary investor in a proposed AltaRock Energy geothermal project in California that would be similar to the one tried in Basel, and the first such project in the United States, the Times reported.

David Blackwell is the SMU geophysics professor spearheading the geothermal energy map project funded by the Google grant. Contacted by the Observer, Blackwell expressed irritation with the Times story on Basel and AltaRock’s proposed California project.

“There was one mistake that was made where people didn’t know what they were doing, and it’s been blown completely out of proportion,” he said, declining to comment further for this article.

The morning Blackwell spoke with the Observer, the Times had published a follow-up story saying Energy and Interior department officials had indefinitely shelved the California AltaRock project due to its unknown potential to cause earthquakes. Officials had previously told the Times that AltaRock failed to fully disclose what happened in Basel.

SMU’s ties to the energy industry notwithstanding, the two SMU scientists monitoring the North Texas earthquakes appear to be free of direct conflicts of interest and are not involved in the Google mapping project. They are Brian Stump, professor of earth sciences, and Chris Hayward, Geophysics Research Projects Director. Their primary research at SMU involves seismic monitoring of nuclear explosions, a study funded by the Department of Defense.

Chesapeake’s only contribution to SMU was $5,000 for an oil and gas symposium held at the university in 2005, an SMU spokesman says. Aside from the loan of seismic equipment, funded mainly by the National Science Foundation, Stump and Hayward have received no funding for the seismic study project, they say.

“We want to get to the bottom of this as much as anybody else does,” Stump says, insisting that SMU’s ties to the energy industry have no bearing on their research.

This summer isn’t the first time Stump and Hayward are studying area earthquakes. Last November, after the fall earthquakes, they deployed six seismic sensors around the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport. Stump and Hayward analyzed data from those sensors, removed in January, as they worked for months in collaboration with Cliff Frohlich, associate director of the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics and co-author of Texas Earthquakes, to understand the quakes in that vicinity and determine a likely cause.

Likewise, data from this summer’s Cleburne quakes will take months for analysis and peer review to ensure accuracy and objectivity, Stump says. The scientists say their data will be analyzed by them and Frohlich and be available to the public.

SCIENTISTS PUZZLED

One piece of information SMU scientists hope to glean from their research is a better understanding of how deep the quakes are originating. Some geologists believe the earthquakes come from deeper than drilling has reached, and are thus unrelated.

Nailing down exactly what the industry has done could present another challenge.

The earthquakes near the DFW airport were close to gas wells set up just last year, Frohlich told the Observer this summer. That seemed to indicate fracturing or other gas well activity was a likely cause.

“The difficulty is knowing when people are actually doing the fracturing,” says John Nichols, an associate professor at Texas A&M University who studies death statistics from earthquakes around the world.

Though not involved in the seismic study in North Texas, Nichols says data from area gas operators showing when and where they have fractured could help SMU scientists ascertain whether there’s a relationship between that activity and the earthquakes.

As of mid-July, when interviewed by the Observer, SMU scientists said Chesapeake had not shared that data with them but that the researchers were still early in their investigation process. In the interview, Stump sounded doubtful that fracturing was causing the quakes but didn’t dismiss the idea. Gas well activities, such as injecting or extracting fluids into or from the earth’s crust can cause earthquakes, Stump said, but many other areas of the state have drilling and fracturing without earthquakes.

“There’s something peculiar going on here [in the DFW area] that’s not going on elsewhere,” Hayward said in mid-July.

Though they had not mentioned the theory about the DFW airport saltwater disposal well to the Observer during that interview, SMU scientists by that time might already have met with Chesapeake officials about it. An Aug. 14 report by Bloomberg says that Chesapeake shut both wells after learning on June 29 from university seismologists that the center of some quakes lay near the base of one of the wells.

Most people didn’t learn of the suggested connection until mid-August. An Aug. 13 press release from SMU quotes Stump saying the DFW area earthquakes-at least those recorded with seismic sensors in place from early November to early January—are more likely to relate to Chesapeake’s saltwater disposal well at the southern end of the DFW airport than to hydraulic fracturing. Waste fluid pumped into the disposal well was injected “well below” the depth of the gas producing zone, the press release says.

But the earthquakes and saltwater disposal well have only a “possible correlation,” and more study is needed, Stump says in the press release.

At this point, the saltwater disposal well theory relates only to the quakes near the DFW airport, and not to the ones in the Cleburne area, he says.

Nonetheless, Frohlich told the Observer this summer that natural gas activity around Cleburne “certainly is suspicious.”

Similarly, more than one geophysicist with the United States Geological Survey is intrigued by the prevalence of natural-gas industry activity near the North Texas earthquakes.

In a recent interview with the Observer, USGS research geologist Russell Wheeler recalled a situation in the 1960s when the U.S. Army was trying to get rid of some liquid toxic waste on the north side of Denver. The army drilled a couple miles into the earth and began pumping the fluid in, but the process was halted when earthquake

resulted, he says

Paul Caruso, a geophysicist with the agency’s National Earthquake Information Center in Golden, Colo., wanted to know when natural gas drilling started in the DFW and Cleburne areas.

Told that the boom began in 2001 and has accelerated in the past two years, Caruso says, “That’s all I’m going to say about that.”

Is it related to the earthquakes?

“I’m not going there,” he said, and suggested looking up “induced seismicity.”

Induced seismicity refers to earthquakes and tremors triggered by human activity, which tend to be of low magnitude.

Triggered quakes often make a loud tearing or roaring noise, according to the June Times story on Basel’s quakes.

“Triggered quakes tend to be shallower than natural ones, and residents generally describe them as a single, explosive bang or jolt—often out of proportion to the magnitude—rather than a rumble,” the article reports.

One person involved in the Basel project who experienced a quake there described hearing a noise like a supersonic aircraft. A woman quoted in the story said she thought a bomb had gone off.

Witnesses in DFW and Cleburne have used much the same language to describe earthquakes there.

“It’s just like a boom,” says Garland Bishop, 48, of two earthquakes he felt in June at his home just outside of Cleburne. “…It feels like a bomb went off, like an explosion.”

White, the Cleburne councilwoman, felt the June 2 quake while at home on the southwest side of town.

“I was at my desk going over my stuff, and there was just a boom,” she said. “It was like a sonic boom or something. I thought the house had blown up.”

Staci Semrad is an Austin-based freelance journalist.