Adios, Reality: Texas Culture Wars Take a Madcap Turn

How a curriculum planning tool called CSCOPE came to fixate the Texas Tea Party.

Above: Jeanine McGregor leads a CSCOPE presentation in Marble Falls in February.

For a Marxist indoctrination plot, it started innocently enough.

In the mid-1990s, school leaders across Texas were searching for ways to make sure all their teachers followed the state’s new course standards, the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills, or TEKS. There are hundreds of standards in each subject and grade, and even the best textbooks don’t cover them all.

A group of East Texas school administrators came up with the idea to create a bridge from the new standards to the classroom. Alignment and curriculum mapping were popular ideas at the time, thanks to an education researcher named Fenwick English, and based on his ideas they built a curriculum schedule aligned to the TEKS, with accompanying sample lessons and tests. At first they kept all these pages of calendars, teacher instructions and handouts in thick binders, but the lessons and standards had to be changed too often. In an ambitious move for the time, they made it all digital.

It was a small program back then, but it spread from Mount Pleasant to Paris and Texarkana, then schools around Corpus Christi and Austin, as regional education service centers in each part of the state piled on and contributed. Today it is much bigger. According to the Texas Education Agency, more than 875 school districts use the program now, and all 20 of the state’s service centers run it together.

Thanks to an improbable tea party-led war that somehow only seems to gain momentum, you may already know this program’s name: CSCOPE.

Here are a few of the other things it’s been called lately: “The online Texas public school curriculum with a name that sounds like an unpleasant hospital exam,” “a massive indoctrinational problem” “straight out of a Marxist handbook,” an “egregious transgression of our most basic Constitutional rights,” a “dismantling of our precious republic” and “absolute garbage.”

Many who were around for CSCOPE’s early days either didn’t return my calls or wouldn’t speak on the record—there have been death threats—but it’s a safe bet most of them are looking at the headlines today and wondering just what the hell happened.

Judy Caskey is one from the early days who will talk. “I’m very proud of CSCOPE,” she says. She’s semi-retired now, but was director of instruction at the regional service center in Mount Pleasant when the program began. She remembers crafting CSCOPE’s philosophy, building its pieces with whatever rudimentary graphics software they had then—maybe ClarisWorks—because they knew it had to be digital, easy to access and change with the times. “It was such a neat journey to go on,” Caskey remembers.

She had Fox News on the TV one day earlier this year, and was shocked to hear them railing against CSCOPE. “I’m like a mother hen with this,” she says. “I get a little bit angry at first, but then I think: ‘They really don’t understand. … There’s a level of ignorance out there, or lack of knowledge, about what this is’.”

It’s not just on Fox News either. In Lumberton, north of Beaumont, a superintendent felt compelled to promise that his schools do not, in fact, support Muslim indoctrination. In Austin, politicians have either ignored the controversy or embraced it as a show of conservative cred. Nevermind local control or academic freedom—when the campaign’s on, the Tea Party gets what it wants.

Prior to launching his campaign for governor, Attorney General Greg Abbott promised to lift CSCOPE’s “veil of secrecy” and “shut them down completely” if he must. Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst and his top challenger for re-election, Houston Republican Sen. Dan Patrick, are caught in a spiral of anti-CSCOPE theater, each hoping their outrage over the lesson plans will win over far-right voters.

Democrats have mostly enjoyed watching GOP lawmakers’ attempts to climb aboard such a strange bandwagon. Republican State Board of Education vice-chair Thomas Ratliff has been a rare CSCOPE defender, calling the controversy a “21st century book burning” that could easily spread beyond this one lesson set.

CSCOPE was always meant for teachers, something most people never needed to encounter. But in Texas schools, where textbooks and standards so easily become proxy wars over social values, anything is fair game for a fight. For the administrators who built and grew CSCOPE with such idealism years ago, it’s hard to recognize their little program the way people talk about it today.

In the back room of a family restaurant in Marble Falls, Jeanine McGregor—a retired teacher who goes by “Ms. Mac”—clicks through a slideshow about her CSCOPE research.

In the back room of a family restaurant in Marble Falls, Jeanine McGregor—a retired teacher who goes by “Ms. Mac”—clicks through a slideshow about her CSCOPE research.

“The brain is really interesting, because you can control the thought process,” McGregor explains. A pheasant is mounted above her in simulated flight, and tea party flags line the wall. “CSCOPE is not a management system. It is a control system.”

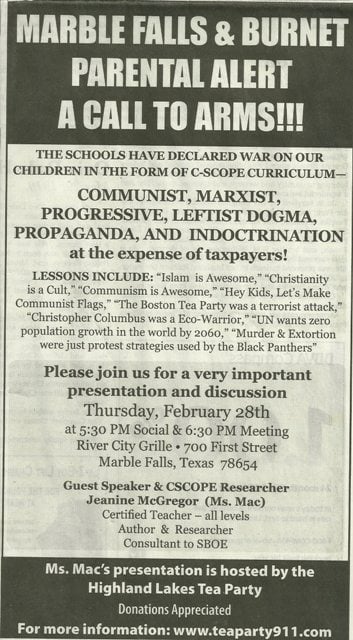

Around 50 concerned citizens are here this Thursday night in February, gasping at the worst of McGregor’s findings between bites of cheesecake. A local newspaper ad invited them here, trumpeting a “PARENTAL ALERT” and “CALL TO ARMS!!! … THE SCHOOLS HAVE DECLARED WAR ON OUR CHILDREN IN THE FORM OF C-SCOPE CURRICULUM.”

McGregor’s got the goods on CSCOPE. She starts with a diagram about how it spends its money, and an organizational chart leading back to Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky—“a Marxist and an atheist,” she notes—who’s been dead since 1934.

McGregor critiques the “progressive” educational philosophy evident in the program. She complains about plagiarism in the program, showing a CSCOPE lesson beside a nearly identical page from another publisher’s text. She describes tests that don’t match the lessons they’ve been paired with, teachers told to use CSCOPE like a script instead of their own lessons. When McGregor says some districts are actually shredding their textbooks and using CSCOPE instead, she gets her biggest gasps of the night.

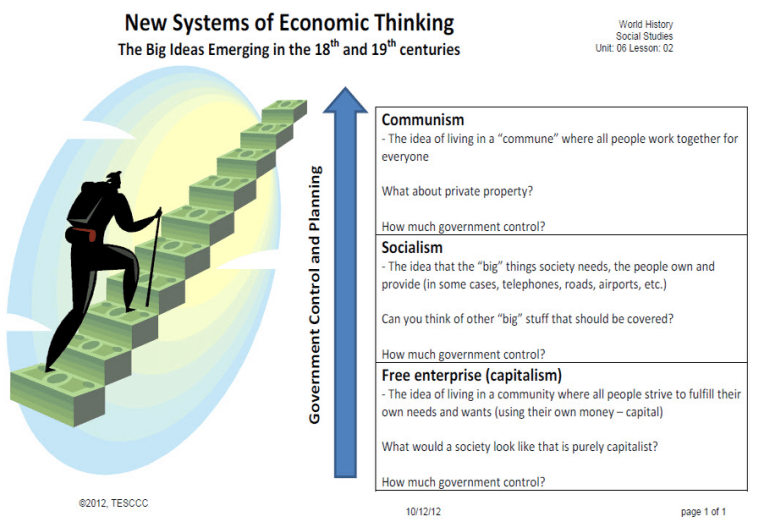

Then come the slides of CSCOPE’s greatest hits: the long-discontinued lesson describing the Boston Tea Party—in a fake news report told from the British perspective—as a terrorist act. In a lesson on Constitutional rights, one made-up character named “Paul Revere,” for some reason, keeps “illicit substances in his home.” She shows slides from a long lesson on Islam, which she says is far longer than any CSCOPE lesson about Christianity. She shows a graphic about economic models from capitalism to communism, illustrated by a man climbing a staircase up to communism. Up!

McGregor tells the crowd that CSCOPE could be hiding far more insidious lessons that just haven’t leaked out yet. (CSCOPE administrators have since made all the lessons available for anyone to review online.) She mentions rumors she can’t confirm, but deems worth mentioning anyway, of CSCOPE’s enthusiasm for Wicca and the globalist United Nations takeover plot Agenda 21.

The mention of that 20-year-old non-binding sustainable development plan probably breezed right by some of the crowd. But for a certain brand of conspiracy enthusiast, it’s a dog-whistle of rare power, and the fact that it’s mentioned at all says a lot about what the CSCOPE scare has become. In coffee shops and community halls across the state, tea party groups armed with the same batch of lessons and charts are helping audiences connect the dots.

CSCOPE, like Agenda 21, has become a kind of secret handshake. In the right crowd, a conversation about CSCOPE isn’t just about different learning philosophies or inaccurate tests. It’s about the certainty that a nefarious, all-powerful hand is at work in the shadows, and that with time and a collective effort, we might know its face. After months of outrage, CSCOPE mania is still going strong, and it all began with one woman in a small Texas town.

Janice VanCleave is all about making science fun for kids. Along with her years teaching science in Texas schools, she’s written dozens of science books for kids, most in the wacky ‘90s heyday of the Complete Klutz and …for Dummies guides. She’s sold more than 2 million copies of books like 200 Gooey, Slippery, Slimy, Weird and Fun Experiments or Chemistry for Every Kid: 101 Easy Experiments that Really Work.

Her latest book was a science guide for home-schoolers, but lately she writes on her blog, txcscopereview.com. One of her first posts there was a sort of anti-CSCOPE manifesto—the anti-Christian stuff, yes, but mostly detailing complaints about science lessons she finds boring or inaccurate. She posted photos from her lifelong love affair with science, freezing at the South Pole or about to go weightless in the Vomit Comet, with her big grin, curly red hair and Coke bottle glasses. This, she wrote, is the kind of science children should learn to love.

Over the phone, she explains how her campaign against CSCOPE began. Two years ago, she volunteered to tutor at a school in Marlin ISD near Waco. She wanted to try out some fun experiments she’d designed, but says she was told the kids’ lessons only came from CSCOPE. The content was proprietary, and she was a competing publisher, so she couldn’t see it. She got approval to see CSCOPE’s lessons from her local State Board of Education member and Education Commissioner Robert Scott—but still the local CSCOPE folks refused.

“What are they hiding?” she wondered.

To find out, VanCleave called her daughter Ginger. “She’s a major researcher,” VanCleave says. “She can get on the web and find all kinds of stuff.” The infamous Boston Tea Party lesson and the slideshow about Islam were some of the first things she found.

VanCleave’s daughter Ginger Russell also happens to be a conservative activist. VanCleave says she wasn’t after a political fight, “Not that I said, OK, get the Tea Party on this,” she says. The Tea Party just didn’t need much coaxing.

Emails about those first few CSCOPE lessons spread, and in November 2012, Glenn Beck spotlighted the Boston Tea Party handout on his show. An email circulated calling on “All Christians in Texas” to come to Austin and help expose CSCOPE’s “humanistic, socialistic, and Marxist philosophy and ideology.” It goes on:

“The use of materials, from highly-suspect liberal sources, is indoctrinating the students without one single review committee. The mental and emotional stress placed on students is showing up in gastro-intestinal problems.”

The Texas Freedom Network called it evidence that “some folks want to turn CSCOPE into the newest ‘culture war’ battle at the State Board of Education,” two years after leveling the same “anti-Christian” and “pro-Islam” charges against Texas history textbooks.

It wasn’t all about Allah, either. For those interested in exposing government waste, CSCOPE’s unconventional management and funding looked promising. CSCOPE is a partnership between all 20 of Texas’ regional Education Service Centers, a landmark project for the semi-state offices that began in the mid-1960s as media libraries. They survive on a mix of state and federal money, plus fees they charge districts for whatever services are in demand. The state has cut its contribution dramatically over the last few years—down to an average of $500,000 per service center today. To make up the difference, lawmakers encouraged the regional centers to be more self-sustaining, to act more like private enterprises.

CSCOPE seemed like just the thing. For $8 a student—less than an off-the-shelf curriculum system from a big publisher—a school district got a program custom-built on the TEKS. Most of the fee went back to the service center near the district, to cover staff and time to train teachers. The rest went to the service center in Austin to manage CSCOPE, pay lesson writers and host an annual conference. CSCOPE’s board—directors from each service center—formed a nonprofit corporation to keep their content from being copied by non-paying customers.

CSCOPE’s critics wondered what that shell corporation was hiding. They howled when CSCOPE dragged its feet releasing minutes from its meetings. If CSCOPE was built by state employees, using state money, they wondered, why are school districts paying for it all over again? The earliest CSCOPE complaints, from teachers who didn’t like being forced to use its prescribed lessons, found new life too as the mania spread. Math and science teachers complained lessons and diagrams weren’t just dry, but simply wrong.

Over the months, the separate critiques all built to a single conclusion. You could go to a town hall and disagree about pedagogy, government spending or even Uncle Sam’s immortal soul, and still agree that CSCOPE was the problem, and it must be stopped.

Into this mighty squall stepped three CSCOPE administrators in late January, as Sen. Dan Patrick devoted his first full meeting as Education Committee chairman to an airing of grievances against the program. It did not go well for the CSCOPE administrators.

Wade Labay, director of Austin’s regional service center, did most of the talking, explaining their financial structure, and why their lawyers suggested they form the nonprofit. As to why parents were being denied access to CSCOPE lessons—why State Board of Education Chair Barbara Cargill had to wait six months for access to the program, he and the others could only apologize. That’s not how it was supposed to work, they said. Asked about the Boston Tea Party lesson, or the classroom activity to design a communist flag, none of them could say just who wrote them or why.

Those weren’t the answers Patrick was looking for. “The more I hear, the more concerned I am,” he said, his voice rising. “Who is in charge, Dr. Labay? Who is in charge?”

When the time came for public comment, all that pressure that had been building for months came spilling out into the committee room. It lasted hours. Stan Hartzler, a math teacher who quit because he was required to use CSCOPE, broke down in tears recalling problems with its lessons. Jeanine McGregor shared her research. “What you’re seeing today is not Enron but Ed-ron,” former State Board of Education member Charlie Garza told senators.

Ginger Russell, VanCleave’s daughter, gave some of the day’s most intense testimony. “The Boston Tea Party’s an illegal act, Paul Revere’s hiding illegal substances in his home, Christopher Columbus’ journal entries have been cherry-picked apart to fit an environmentalist agenda,” she said. “It doesn’t matter what the lesson is about, it’s gonna end up an environmental lesson. They can make Santa Claus into an environmental lesson.”

With the weight of a Senate hearing behind it, the CSCOPE scare got national press from Fox News, the Daily Caller and the Washington Times. Glenn Beck aired a confusing CSCOPE encore with the far-right historian David Barton. “Get your kids out of the public school system,” Beck advised. “Do not let another day go by with kids being indoctrinated.”

The controversy grew both within and beyond the fact-based universe. WorldNetDaily ran an analysis showing CSCOPE school districts scored lower on state tests than districts that don’t use the program—while ignoring variables like poverty or school funding.

Other stories tied the CSCOPE madness to wholly unrelated events. A girl told to say the Mexican pledge of allegiance at school, students photographed wearing burqas in geography class, and a class quiz suggesting America’s foreign policy helped incite the 9/11 attacks—CSCOPE took blame for them all.

In the days after a big news segment on CSCOPE, threatening letters and angry calls came pouring in to the service centers from as far as Arizona, Wyoming and even other countries. “See my nightly reading below,” one service center staffer told another in an email. “I’m telling you…I might need therapy.”

One man wrote to ask for confirmation that “CSCOPE” stood for “Constructive, Socialistic, Curriculum of Progressive Education.” “You are either an un-educated moronic boob,” another email read, “a thick-headed liberal, or an apologist for the islamo-fascists.” Another critic offered a suggestion: “Add this to your curriculum: How about blowing up your building?”

A conference call in February hosted by the group Women On the Wall was billed as a CSCOPE information session, but spiraled quickly into Muslim scaremongering. A national security writer from rural Virginia explained the trouble was all part of a plot to sell out our Christian heritage, championed as ever by “feminists, homosexuals, artists and Jews.”

Near the end of my conversation with VanCleave a few months ago, she made a request: “Don’t make our case look bad. We that work on getting CSCOPE out of the schools are educators. We have a passion for education,” she said. “We spend our own money, we spend our own time.”

But that seems less true as the controversy matures and campaign season picks up. CSCOPE’s directors dissolved its nonprofit and discontinued its lessons—freeing them, according to the Texas Education Agency’s lawyer, into the public domain. No more public money will be spent on the controversial lessons, which teachers can use just like anything else that might help out their classrooms.

The national press has let CSCOPE go, but the online Women On the Wall radio show and its production company, Voices Empower, have kept a steady drumbeat against CSCOPE all this time. The show has hosted Dewhurst, Patrick, Rep. Steve Toth (R-The Woodlands) and attorney general candidate Barry Smitherman to discuss CSCOPE.

Ratliff, the CSCOPE defender, describes the lieutenant governor’s race between Dewhurst and Patrick as “two suitors trying to chase the same woman.” He could be referring to tea party voters in general, but more likely he means Alice Linahan, Voices Empower’s president. She also maintains a website dedicated to impeaching Ratliff.

School starts later this month, and Texas’ teachers are preparing another year of lessons, with big changes to the state’s tests and school evaluations. On campaign stops, though, talk about education will center on a controversy that strays ever further from reality, and further from the classroom.