Backlash to a Rape

A few days after my 16th birthday, a woman walking along a lonely highway in the neighboring town accepted a ride from an acquaintance. She climbed into a car carrying four men. Linda Gaitan was 19, a young mother who wore a tattoo, “Soy Gaitan” (I’m a Gaitan), her husband’s surname. The four men drove Gaitan to an outdoor party—beer and men cheering on their birds in an illegal cockfight. Gaitan was gang-raped on the hood of the car by 11 men and a teenager. The beer, the cockfight, Latinos queuing up for their turns. The details became an open wound with rumors and news reports buzzing around like flies.

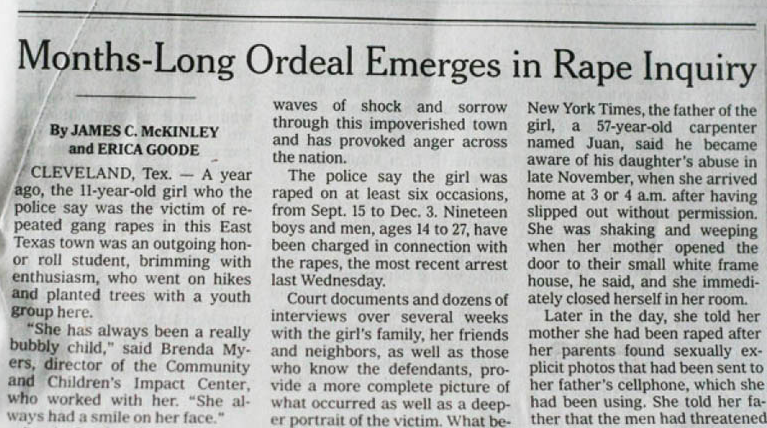

The 1988 rape in San Diego, Texas, swelled in my mind as I read the details of the gang rape of an 11-year-old girl in Cleveland, a small town north of Houston, by 18 males, the youngest 14, the eldest 27. The New York Times and Houston Chronicle coverage included comments by locals who suggested that the girl somehow consented or invited the abuse. Some in Cleveland described the girl as dressing beyond her years, walking around alone. She hung around with teenage boys, they said.

The Chronicle made the questionable decision to include details from the girl’s Facebook page. The Times allowed chaotic reactions from locals to dominate the story, and the response to the coverage was swift and fierce. Some in the community had cast blame on an 11-year-old girl, and the press had given them a free pass. Critics have rightly excoriated the press for failing to provide “context,” the context being that a child can never consent to sex. It’s illegal.

I return to the comments by the locals because they reveal much about the way people, communities and the press process sexual violence. These reactions appear to be imbued with shame, exacerbated by internal politicking and are a reaction to the press itself. The result—battle lines are drawn, camps are formed, allegiances are fortified.

As in Cleveland, the scrutiny of the national media fell on San Diego, and it fell hard. As in Cleveland, local leaders were quick to say that “this really hurts the town,” blurring the line between the vicious crime and the subsequent attention. A local newspaper ran a front-page editorial in defense of San Diego. “In a sense, the national and area news media have raped this town in a fashion not too unsimilar [sic] to the gang rape itself.”

While the “town rape” invoked shame, the actual rape was an abuse, a violation. Drawing the parallel frames rape as a shame against family and community, without regard to the suffering of the victim. Shame is what makes people pick sides, makes them forget the victim to save face.

In 1988, an undercurrent of shame helped rally folks in defense of San Diego and South Texas. We knew that the Anglos (as whites are called) would add this shocking crime to the litany of reprehensible behavior ascribed to Mexicans (as all Spanish surnamed are called). They wouldn’t, and couldn’t, see the crime as a horrific act by individuals. It would be viewed through the lens of culture, race, class and become an indictment against all of us Latinos. The sexy mix of beer, fighting beasts and Mexicans guaranteed it. We were all implicated in the shame. Many people took sides, one side really, the community over the girl. It was that simple.

Their suspicions, as it turned out, were not baseless. The Los Angeles Times report on the rape included a portrait of local poverty-“remove the late model cars”, the reporter wrote, “and you could easily imagine this was the 1950s.” A Texas Monthly cover read “Macho Gone Mad.” In the article, the term “Maldito Pueblo” (“Wretched Town”) was slapped onto San Diego, and the rape became an entrée into the town’s sordid history of corruption and domination by the “Duke of Duval,” George B. Parr. Parr ran the county as a fiefdom with local Mexicans as serfs. San Diego was the site of the infamous Box 13, the “missing” ballots of the deceased that catapulted Lyndon B. Johnson into the U.S. Senate in 1948. These details were deftly used to explain the cause of the crime and the community’s reaction. Implicit in the “wretched town” description, as well as a traveler writer’s observation that there was nothing to do in San Diego “but drink and fornicate,” were the circumstances that led to the crime.

In our little part of the world, poverty was rampant, upward mobility was dim and women with slim job prospects married young. No one, no outsider at least, seemed to give a damn until the rape. I remember the Geraldo Show devoting a segment to the story, and I cringe even now. Why does the victim keep talking, people wondered? As if her voice was the reason for the shame, not the men.

Back then, I was an emerging rebel who took the floor in government class and argued against any complicity by the victim. She accepted a ride. She didn’t consent to sex, and her decision wasn’t reflective of her character. (Walking on the street in small town Texas will, to this day, draw stares. Only the downtrodden walk.) I remember my indignation and outrage. It was rape, and it was wrong. I was being naïve about the reality of life and justice.

It’s been 23 years since the nation’s attention fell on San Diego. The events unfolding around the crime in Cleveland are much the same. Some of the men and boys arrested in Cleveland belong to the privileged class of the community: the son of a school board member and several basketball stars. Stories about a rape expand into explorations of the community, its segregated history, the history of racial strife, as if understanding these aspects of Cleveland helps to understand why the crime occurred.

These details may explain reaction, but not why the crime occurred. I doubt we can ever resolve the reporters’, and by extension the public’s, nagging question: Why?

In Cleveland, the painful situation is made more complex by the ever volatile issue of race. The victim is Latina, and all of the arrested males are African American. The arrests have reportedly fueled racial divisions in Cleveland, where half the population is white and the other half split between Latinos and blacks.

“It’s becoming a black and white issue because it happened over in the quarters. It’s segregating our community again,” Brenda Myers a local told the press, referring to the African American neighborhood, “the Quarters.”

On the eve of a Houston activist’s town hall meeting in Cleveland, a Houston Chronicle columnist noted: “In a place like Cleveland, where the black side of town is still known as the Quarters, it’s not beyond reason to question whether race is playing a role.”

But the ‘role’ is not defined. Was it a factor in the crime, the arrests or the quality of justice that will follow? Once again, lines are drawn and choices made. An 11-year-old girl or the town? Race or gender? Missing from coverage of this story is the realization that the nature of the media reaction forces people to take sides. We outsiders and journalists are not mere observers but participants.

Meanwhile, substantial questions are left unanswered: Why did three months elapse between the start of the police investigation and the arrests? Why did the judge place the victim in a foster home and restrict access to her family? A spokeswoman for the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services said the agency was under a gag order. Does separating her from her family victimize her again? Has evidence of neglect or family abuse surfaced to warrant the ruling? Why is the family being targeted? Why have they been urged to leave their home? In a small town with close ties, who is watching the investigators and the courts? The courts will sort through the details of the crime. We should be vigilant of the caliber of justice dealt to the accused and the interests of the girl.

I realized years later that, after the Gaitan case, my relationships with men became tinged with aggression and wariness. It was the confused reaction of an angry girl who had learned unspoken rules about sexuality and blame. I watched a woman be sacrificed by my community, and I felt betrayed. As Cleveland draws its lines around race, power and reputation, I wonder if girls there—white, black, Latina and Asian—feel like I once did, scrutinized by outsiders looking in, but abandoned at home.

Michelle Garcia, a native of South Texas, is a writer and producer based in New York. She’s a former writer for the Washington Post and co-founder and director of the Border Mobile Journalism Collective, a citizen journalism video project on the U.S.-Mexico border.